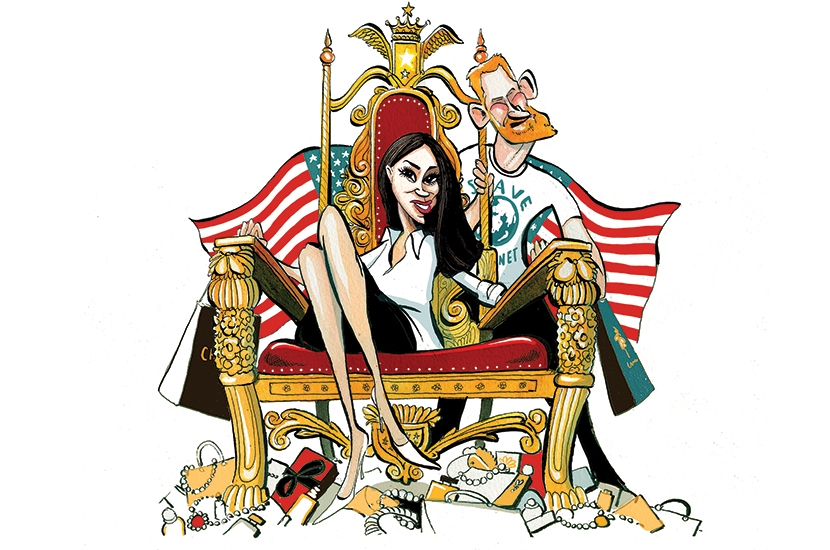

Prince Harry is now chief impact officer for BetterUp, a Californian corporate consultancy whose ‘mission’ is to sell online life coaching with — in his words, — ‘innovation, impact and integrity’. Harry may not realize it, but he is the latest celebrity frontman for the rapidly growing, broadly unregulated and frequently dubious corporate ‘coaching’ industry.

BetterUp is one of a group of Californian companies on the growing, corporate edge of life coaching. Its competitors have names like Workbot, Hone and Clear Review and they all claim to have discovered the secret to improving motivation and productivity at every level of corporate life — using data modeling and artificial intelligence to target what BetterUp calls ‘hyperpersonalized coaching’ at every employee. Imagine Big Brother running the department of human resources in the voice of an especially insistent yoga instructor. Imagine a future in which your boss feels you’re not productive enough, so he sends you to online therapy to make you a better worker, and receives reports on your innermost emotions.

BetterUp was co-founded in 2013 by a 27-year-old Texan named Alexi Robichaux. At the time he was, he says, ‘bummed’ by his experiences as a Silicon Valley product manager and ‘soul-searching’ for a better way to do digital business: ‘I started to look for help and engaged in everything from executive coaching to life coaching to therapy to self-help books. I even walked across Spain on the Camino de Santiago.’ Robichaux says that his vision ‘crystallized’ on his pilgrimage: to ‘use technology to scale coaching and make the lives of millions of professionals better’.

BetterUp now calls itself the world’s largest coaching network. It has 270 full-time employees, and subcontracts the services of 2,000 coaches to more than 300 companies, including Nasa, Hilton, Chevron and Warner Media. In February, BetterUp’s market value was more than $1.7 billion. And that was before the wave of publicity and interest when Prince Harry joined the firm.

In early March, three weeks before Harry announced that he’d ‘personally found working with a BetterUp coach to be invaluable’, the company launched two new products, Identify AI and Coaching Clouds. Identify AI gathers data on every employee — ‘where each person is in their career, their mindsets and behaviors, learning preferences’ —and assesses their ‘readiness for coaching’. It then filters this information through a company’s ‘strategic priorities’ to identify ‘who the right people are to invest in, and the appropriate dosage and type of coaching needed to best meet their needs’.

Coaching Clouds comprises three layers of hyperpersonalized coaching. The top layer, Executive Coaching, will keep you in the corner office. In Professional Clouds, coaches with ‘at least 10 years of prior corporate coaching’ mentor ‘emerging leaders and high potential individual contributors’. The third format, Field Cloud, is aimed at ‘frontline employees’, cannon fodder like ‘customer service agents and retail associates’: call centre workers, for instance, who are coached to show more ‘empathy’.

Robichaux claims BetterUp’s data demonstrates that when employees are ‘offered learning programs tailored to their preferences, they put twice as much effort into learning and development, and experience a 180 percent increase in job effectiveness’. He doesn’t say what happens to employees who refuse the offer or dislike the dosage, or lack the requisite ‘readiness’ to submit to cod-psychiatric management-speak.

BetterUp claims to give its clients a ‘validated, quantitative measure of the impact of our service’. But there is no external assessment, and the validation and quantitative measurement are as arbitrary as BetterUp’s sales pitch. For BetterUp, ‘meaning’ and ‘satisfaction’ lie in the directing of work towards a collective goal. But there can be no objective measure of how people feel about their jobs. Consider Meghan, Duchess of Sussex’s dissatisfaction when she was temping in Britain, and how she felt about The Firm’s collective goals.

And who would dare to tell the boss that they think it’s intrusive of BetterUp to ‘isolate’ the ‘psychological factors’ that determine ‘whether, short of a medical emergency, an employee chooses to come to work’, or that it’s manipulative to use an algorithm to detect individual failures in nutrition and sleep? Who’d dare suggest that it can be irrelevant whether a worker is insufficiently keen on ‘diversity and inclusion’? Or even that BetterUp is a sinister waste of time?

Laszlo Bock, who worked on Google’s attempt at data-driven HR, calls the promise of data-driven efficiency ‘Silicon Valley fairy dust’. Peter Cappelli, a professor of management at the Wharton School of Business, believes that there is ‘virtually nothing — indeed, nothing I can think of — at the level of the individual employee that clearly drives revenue and so forth. There are far too many steps in the chain’.

Business coaching and life coaching are the modern faces of what the Boomers called the Human Potential Movement. The HPM’s godfather was Abraham Maslow, who devised the now-ubiquitous hierarchy of needs, a triangle with the physiological basics at the bottom and ‘self-actualization’ at the top. The goal of therapy was no longer Sigmund Freud’s modest aim of reconciling the patient to ‘ordinary unhappiness’; it was unleashing everyone’s innate genius.

Not surprisingly, the HPM took off in 1960s California. Incubated at the Esalen Institute at Big Sur, it became the counter-culture’s way of doing self-help: the long, strange trip of encounter groups, Gestalt therapy, Zen, holotropic breathwork and Transcendental Meditation.

As the Boomers aged, the seekers and swingers in the hot springs at Esalen mutated into the spiritual businessmen of the 1970s and 1980s. In 1971, Werner Erhard, a car salesman influenced by Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, launched Erhard Seminars Training in San Francisco. EST was a therapeutic bootcamp: no wristwatches, no bathroom breaks, no talking until spoken to. The goal was to force rapid enlightenment about personal potential through ‘ruthless compassion’. Erhard is still alive and highly litigious, so you’ll have to look online to read how he beat accusations of incest, bullying and tax evasion. In 1984, he launched a less ruthless version of EST, the Forum. Its successor, Landmark, is still going. You may be familiar with the glassy-eyed zeal of graduates of its three-day psychotic break, the Landmark Forum. They sound not unlike Prince Harry when he gushes about ‘peak performance’, ‘transforming pain into purpose’ and unlocking ‘potential and opportunity that we never knew we had inside of us’.

There is no federal oversight of America’s coaching industry. Anyone can call themselves a ‘life coach’ or a ‘business coach’. BetterUp says that its coaches are ‘ICF-certified experts or licensed therapists’. The ICF is the International Coaching Federation. Its founder, Thomas J. Leonard, worked at EST in the 1980s. He also founded the International Association of Coaching, which sells ICF-accredited courses, and CoachVille, which sells add-on training and coaches the coaches at its Center for Coaching Mastery.

The ICF is not a neutral self-regulator like the American Bar Association. It is part of the coaching economy. Apart from selling accreditation, the ICF runs a Coaching in Organizations program for businesses, and a Thought Leadership Institute that ‘facilitates interaction between innovators, technologists, venture capitalists, press and influencers’. It also sells tickets to ICF Converge, its annual seminar for coaches.

The modern coaching industry is to Sigmund Freud what Ronald McDonald is to Auguste Escoffier. Workers are sliced and diced into profiles through digital astrology. Corporations love this because it promises to raise productivity and reduce healthcare costs. Insurers love it for the same reasons.

It’s almost painful to think that Prince Harry believes his enlistment as a corporate mascot will have a positive impact on mental health in the boardrooms and call centers of America, when the only impact of him serving as the credulous face of a dodgy and shoddily regulated industry will be to embarrass his family once again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.