I couldn’t disagree more with Sir Keir Starmer (it was ‘completely wrong,’ ‘it shouldn’t have been done in that way’) or with Boris Johnson (‘if people wanted the removal of the statue there are democratic routes which can be followed’). No, there was something magnificent about the sight of the Bristol mob throwing into the harbor the statue of a man whose trade was notorious for throwing sick slaves with no monetary value into the sea. 1890s Britain raised that statue. 1890s Britain — the decade in which my grandparents were children, for heaven’s sake — had only just closed the slave market in Zanzibar: and if you want to know more about that stain on our fairly recent history, read Alastair Hazell’s enthralling, horrifying The Last Slave Market: Dr John Kirk and the Struggle to End the East African Slave Trade.

If we’re entitled to feel pride at the achievements and virtues of our forebears, why should we not feel shame at their sins? If there is significance in erecting monuments to those we admire, who can deny the significance of tearing down monuments to those we don’t? Be honest. The sculpting of a massive representation of Sir Edward Colston for public display was not an exercise in either history or biography, it was a salutation plain and simple. And if 1890s Britain was free to raise a monument to a man whom many of the residents of Bristol wished to salute, 2020s Britain should be free to raise two fingers to a man whose memory their successors hate. Toppling that statue was not an attempt to ‘erase history’, as disgruntled conservatives like to mutter. Of history: ‘The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ, /Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit / Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, / Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.’ No, that statue was not about history but estimation. Our era is entitled to its own response. Far from this being a ‘writing out of history’ it was a writing in of history. History is what happened.

How dreary, then, to recommend that instead of letting people show their passion unbidden and un-minuted, the statue should instead have been demoted by a deliberative committee of municipal worthies, followed by the sending of a van with council workers in hi-vis jackets, and the despatch of the bronze to some dull and unvisited corner of a museum somewhere. Sir Edward went out not with a whimper but with a bang, and the video of the statue going into the harbor is now already in the modern museum that is the internet. That day has become, itself, history: history made not by an item on the agenda for councillors and bureaucrats, but by the impulse of an angry crowd.

Watching the videoed scene of the mob toppling the bronze Sir Edward over the quayside last week, I felt a kind of thrill at the beating heart of human beings responding viscerally to a piece of art. The statue, of course, was more than an item of fairly un-exceptional art: it served as proxy, as ‘heroic’ sculpture does, for its subject, in this case Sir Edward. But then serving as proxy for the things it may represent is what a great deal of art is all about. Just as it is good when art lifts, inspires, ennobles and pleases us, it’s good too when art infuriates, hurts or inflames. Good in both cases because art has engaged. As something in me resonates at people’s rage against a material object serving as proxy for what they hate, so I also thrill to people’s rage against art itself, art they do not like: for this too is a function of art — to engage.

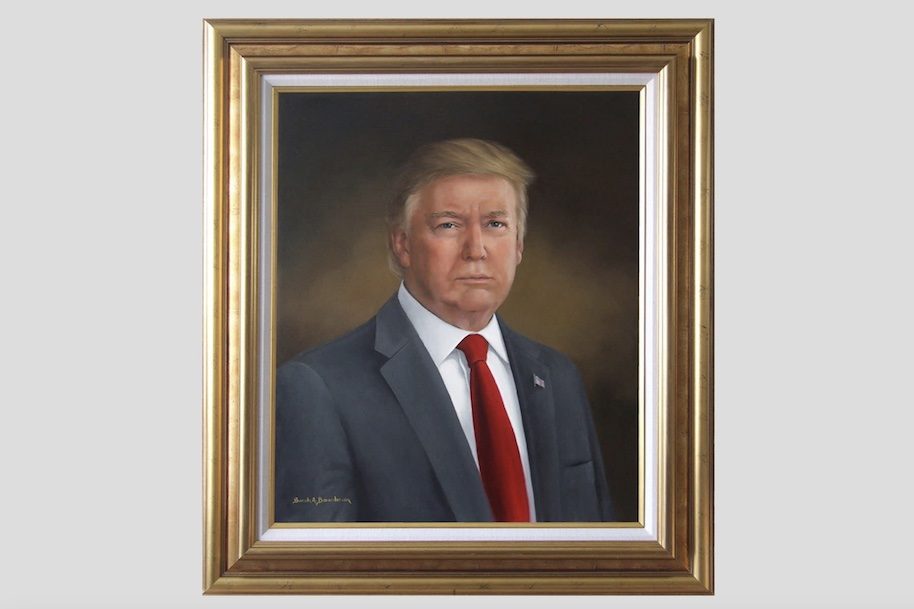

In November 1954, on his 80th birthday, Winston Churchill was formally presented with his portrait by one of our most notable 20th-century artists, Sir Graham Sutherland. The painting (in my view a masterpiece) is of a figure at the same time peevish and heroic, obdurate and defiant, fat, bull-necked and irascible, with a hint of hurt in the eyes. The portrait is completely and infuriatingly him. His political enemies tended to think it was rather good; his friends mostly took the other view.

Churchill detested it, said it made him look like a drunk propped up from the gutter, accepted this gift of both Houses of Parliament with what grace he could muster (not a lot), took it to Chartwell and sent it down into the basement. After Lady Spencer Churchill’s death, it emerged that she had had it removed and burned.

[special_offer]

I call that act of aggression against art a triumph for art. Art should delight, wound or enrage. Lady Spencer Churchill’s vandalism was the ultimate tribute to honest portraiture. I see the whole episode as a celebration of the power of figurative representation to arouse passion in the breast of the viewer; and passion will take its natural course. Sutherland’s art had cut his subject to the quick. Sutherland was entitled to his artistic response to Churchill, and the Churchills were entitled to their response. This is where art should be: not on elaborate plinths or the walls of hushed galleries, but at the center of attention and human passion. Whether the passion is sympathetic or antipathetic is secondary.

Heroic sculpture is multidisciplinary, hovering between art, craftsmanship and historical tribute. Colston’s bronze, like Sutherland’s oils, is a commentary. To see these commentaries engulfed in the flames of a wife’s anger, or drowned by Bristolians in Bristol harbor, is to see art come out of the galleries and textbooks and tourists’ snapshots, and into our hearts and spleens.

Thus perished most of the innumerable monuments to General Franco that I remember from parks and squares in pre-1970s Spain; thus came down the statue of Saddam Hussein, whose toppling in Baghdad was (so far as I remember) unaccompanied by much regret from we who are of a conservative habit of mind. And thus fell a slave trader’s monument. In the destruction of art’s handiwork, art shows it matters, comes alive.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.