Now that the government has kindly allowed us to go out again, I wonder if anyone has discovered the same social challenge I have encountered? Which is that almost nobody agrees on anything. I should pre-empt a possible line of attack here and acknowledge that I am aware of the case study I am basing this on. Still I fancy the problem is wider than myself.

Of course we never did agree on everything. But, after a year of seclusion, it seems that as we de-bubble, the divergences are far greater than before. Not least regarding what we have just been through.

It forks off at the very beginning. For instance there are people — few in number, and perhaps not in your own circle of acquaintance — who basically disbelieve the whole COVID thing. They think it is a hoax or fraud or some great ploy by Klaus Schwab, the IMF or others. These people then have a million little divergences and fallouts of their own. But among those of us who believe it is real we have an equal range of divergences.

There are those who think that it is an exceedingly deadly virus which demanded the shutdowns and isolations of the past year, and those who believe that to varying degrees the virus is not much worse than an average flu year and that we have just inflicted a wholly unnecessary act of collective self-harm. I have noticed that these two relatives get on especially badly, for obvious reasons after a year of sacrifices.

All this is before we get on to the fork in the road on the origins of the virus. As Matt Ridley brilliantly showed the other week, there has recently been a very swift and sharp turnaround in the official narrative about the virus origins.

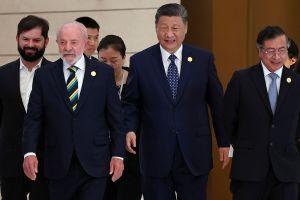

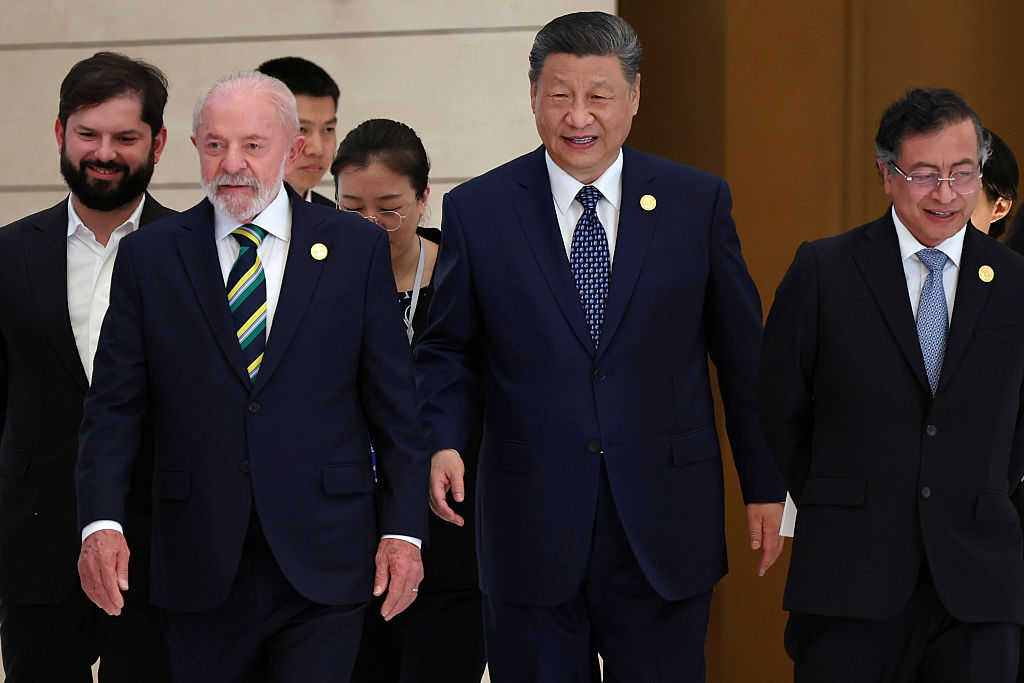

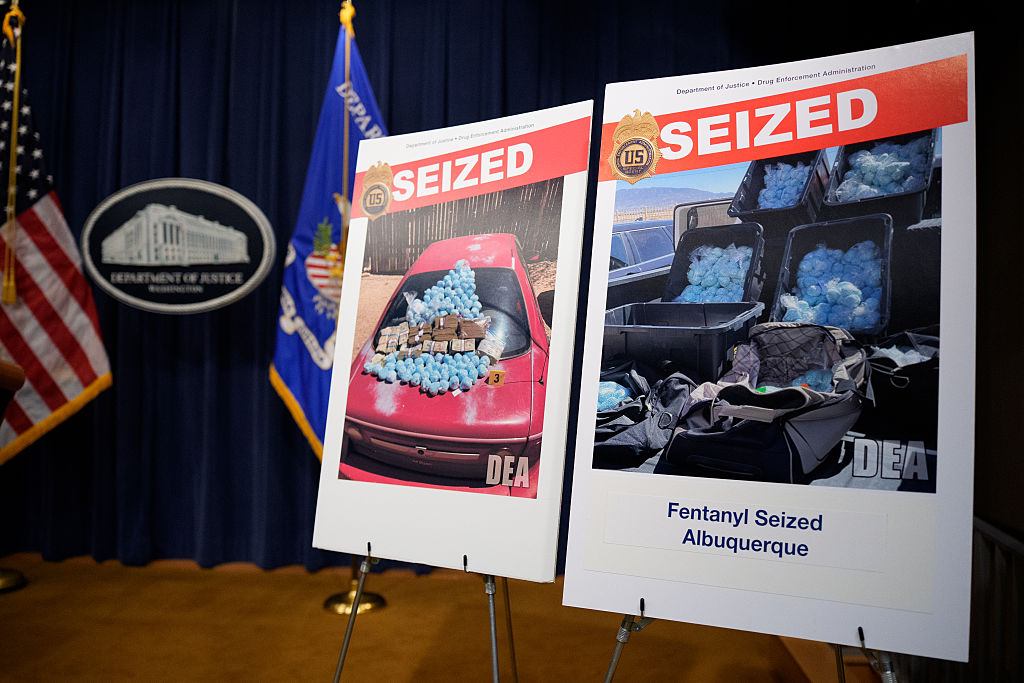

Those of us who said from the start that there was something fishy about the coronavirus leaking from an area that happened to have a CCP laboratory looking into precisely this type of virus have spent a year being derided or shushed. It was conspiratorial nonsense, we were told. The bat-eating story was the only palatable one that any decent person would discuss over our then virtual dinner parties. Now the story has changed and the wet-market people are coming over to the laboratory side. But not in overwhelming numbers.

Even that forks out again. Both the adherents to the bat story and the adherents to the laboratory story now each have a further fork to navigate, which is whether this was deliberate or not. You may say it does not matter, or you may say we will never know. But the question of whether China deliberately or accidentally leaked a virus that shut down the world’s economy might in due course be regarded as a matter of some interest.

And all of these divergences come before we arrive at the vast divides over what to do about it. In social situations I have noticed that people now observe a nervous, uncertain game over what to do with each other. All social greetings have taken on the tentativeness of a couple of teenagers trying to work out who should make the first move. I’ve done my share of cheek-kissing, hugging and even handshaking again of late, largely in the belief that if you think it’s safe enough to leave your front door then you should accept the fact that someone might extend a hand at you. But not everybody is pleased with this arrangement. Some people leap back. Social niceties we all performed till March last year have taken on the delicacies of the #MeToo movement.

Then there are the mask wearers, of course. I doubt some people will ever be prized out of theirs. Double-vaccinated people who have no health risks still have them clamped to their faces as they walk down the street. Will they ever discard them? One woman recently told me stridently ‘So you’re just going to kill me, are you?’ as she spotted me maskless at something. And though the thought hadn’t occurred to me before, as I contemplated her the idea did begin to take on a certain appeal. And this is all before we get to the vaccine debate, the debate about vaccinating children against a virus that does not affect them, and the question of whether the vaccinated ought to view the vaccinated as irresponsible. Or vice versa.

So on a cursory recce back on the social scene here are the things we disagree on. We disagree on where the virus came from; whether it is an act of biological warfare or not; how dangerous it is; what to do about it; how to mitigate the risk of it; and how, if ever, we might return to normal life.

It is possible that I have a more varied and difficult circle of friends than other people. I would certainly hope so. But in my circle of acquaintance I would say that I have friends who cover all of the above categories of thought, and all with their unique cocktails of different elements which it is hard if not impossible to predict. I know octogenarians who have been racing out of their houses and younger people who have needed to be prized out of theirs. I know sane people who have become conspiracy-minded and conspiracy-minded people who are currently glowing from the satisfaction of certain of their warnings being borne out.

And as I contemplate all this, it strikes me that this, incidentally, is what plagues in history always do. The plague of Justinian, the Babylonian plagues — all of them. The record shows that when they sweep across the land, they do many things apart from killing people. One of these is that they cast a great blanket of doubt over everyone. They make people suspicious of each other, and fearful of others. People who don’t know where death might come from develop deep doubts and uncertainties. The society’s underlying fears and fractures come to the surface and new ones also present themselves. A form of chaos emerges in the land. So it is history in action, I suppose. A thing which it is always interesting, if not especially pleasant, to live through.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.