New Zealand’s parliament adjourns this week, officially kicking off six weeks of political campaigning ahead of a general election on October 14. But it seems that Chris Hipkins and his Labour party might find it difficult to maintain their grip on power.

Persistently high food prices at the supermarket, and a string of cabinet mishaps have seen a waning in support for Hipkins’s Labour government. For the first time, he has found himself on a level pegging with Christopher Luxon, the leader of the National Party, in the race to become prime minister. Several weeks ago, a poll conducted by pollsters Taxpayers’ Union-Curia, revealed support for the Labour government stood at 27 percent, while the opposition National and ACT parties commanded 34.9 percent and 13 percent respectively — enough support to form a government.

The decline of Hipkins’s Labour government in the polls is coinciding with a deeper antipathy

The poll also showed the minor party New Zealand First, led by the aging populist maverick Winston Peters, above the 5 percent threshold and returning to parliament. Peters first entered parliament more than four decades ago, and held the balance of power in three elections before being ejected from parliament at the 2020 election. If New Zealand First manages to return this fall, it would certainly represent an abrupt reversal of fortunes.

A week prior to the Taxpayer’s Union–Curia poll, an Essential poll New Zealand by the Guardian also put the country’s center-right opposition firmly ahead of Labour. According to the survey, the National and ACT parties recorded the majority support needed to form a coalition government. Labour managed 29 percent, with their ally, the Green Party, polling at 8.5 percent. Meanwhile, the National Party recorded support at 34.5 percent and ACT received 11.6 percent. The poll also tipped New Zealand First to return to parliament on 5.3 percent of the vote.

The Labour Party currently has sixty-two Members of Parliament in the 120 seat-parliament after an unprecedented victory in 2020 at the height of former prime minister Jacinda Ardern’s popularity. The troubling issue for the party now is the consistent trajectory of its polling. For context, a Roy Morgan poll conducted in June showed a potential right-leaning National/ACT NZ coalition with a lead of 45 percent, ahead of a Labour/Greens coalition on 40 percent. The polls from earlier this month show their popularity is continuing to tumble.

Furthermore, Labour has ruled out any alliance involving New Zealand First. In their place, the National Party’s Luxon has hedged on the possibility of working Peters.

The cost of living has weighed heavily upon Labour’s fortunes. The latest data from Stats NZ showed that annual food prices are continuing to soar, up 12.5 percent in June compared to June of last year. July was the fifth month in a row that the monthly cost of groceries rose at roughly triple the rate of pre-pandemic prices.

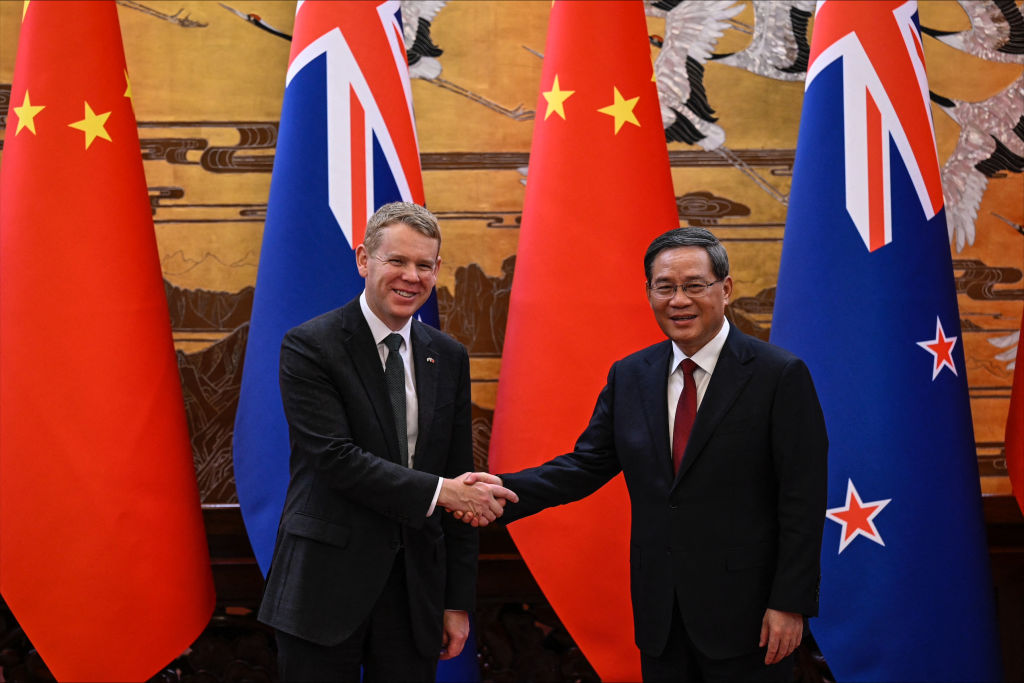

When he became prime minister in January, Chris Hipkins brought an easy going, subdued appeal to the job. Combined with a managerial approach to governance, this seemed to strike the right chord after the loftier but somewhat abstracted idealism of his predecessor, Jacinda Ardern.

However, if the economy languishes and ministers succumb to errant behaviour, a leader with such characteristics runs the risk of looking weak, unassertive and unable to wrest back control. Unfortunately, this seems to be the narrative which has taken hold around Hipkins.

Hipkins’s latest cabinet shake-up took place following a car crash in Wellington involving Justice Minister Kiri Allan, who had been contending with mental health issues. She subsequently resigned from all portfolios. How Hipkins dealt with the issue wasn’t seen as dithering, so much as that he was overtaken by circumstances; maintaining a low-key, easy-going manner has started to look incongruous and feel inadequate.

Through most of the twenty-first century, Kiwis have consistently described the country as being on the right track. This has been in marked contrast to many other liberal democracies beset by polarization and distrust in governments and institutions. The decline of Hipkins’s Labour government in the polls seems to be coinciding with a deeper antipathy — a belated but perhaps inevitable corrosion.

The political resurrection of the populist Peters can be attributed, in part, to ambiguities around notions of “co-governance” with indigenous Māori. Co-governance has existed in a variety of forms during successive New Zealand governments. The term refers to the shared management of affairs and resources with iwi (Māori tribes), including Māori representation in local government, environmental management and a Māori health authority. It has become a wedge issue in the country, and is being drawn up as a key election battleground for this year.

The issue for some voters is the ambiguity over the extent to which, or indeed whether, any given initiative with Māori is symbolic or aspirational, or to be codified in law with real-world applications. Hipkins acknowledged that the term could mean different things in different contexts: there were examples of co-management in various Treaty of Waitangi settlements, for example, many of them negotiated under previous National governments. Opposition leader Christopher Luxon had been grilling Labour over the issue for months, saying they have failed to adequately explain co-governance measures to the public.

For New Zealand, the recent raft of polling does not guarantee a National-led government — there is plenty of time for a lot to change between now and October 14 (not least a Rugby World Cup knock-out semi-final potentially featuring the All Blacks perilously scheduled that morning). But it will take an immense effort for Labour, re-elected with a historic majority just three years ago, to have any kind of chance at all of clinging on to power.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.