The top commanders of China’s nuclear forces have been targeted by President Xi Jinping in his latest purge, adding an extra layer of intrigue to the unexplained disappearance of Qin Gang, the country’s foreign minister.

On Monday, Chinese media announced that Wang Houbin, a former deputy commander in the navy, has been appointed head of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, which oversees China’s conventional and nuclear missiles. This is the first time in forty years that the top job has gone to somebody outside the unit. Li Yuchao, the previous head of the force, has been missing for weeks and several other top officers, including two of Li’s deputies, have also disappeared. China has said nothing about their whereabouts, but the South China Morning Post reports that they are being investigated by the Central Military Commission’s anti-corruption unit, citing military sources.

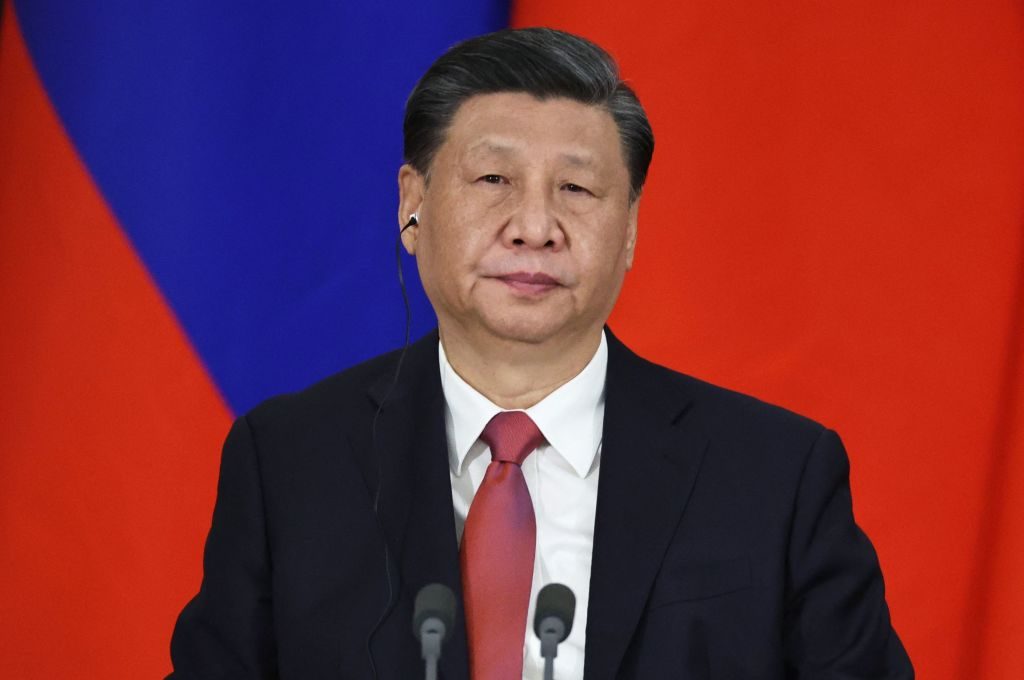

On state media a formal photograph of the new generals has been published, with a stern looking Xi standing at the front. In its news reports, the state media used Xi’s title of — “Chairman of the Communist Party’s Central Military Commission” — a reminder that the PLA is first and foremost a party organization. Last month Xi told PLA commanders they must enforce “the party’s absolute control over the military.” The Central Military Commission also called for an “early warning mechanism for integrity risks in the military.” Rumors about purges at the top of the most secretive and sensitive branch of China’s military have been circulating for weeks.

“Corruption” is a catch-all accusation used by the party as a cloak for all manner of misdemeanors, real or imagined. It is frequently a veil for the purge of political opponents or those deemed insufficiently loyal. Speculation has inevitably centered on whether the purged commanders leaked military information at a time when China is undertaking a substantial expansion of its nuclear arsenal.

What is harder to say is whether the turmoil among China’s rocket men is related directly or indirectly to the disappearance of Qin Gang, who has not been seen since June 25, and who has now been replaced as foreign minister by his predecessor Wang Yi. One suggestion is that Qin Gang was compromised in some way — even that his alleged mistress was a double agent.

China’s rocket force will have been of special interest to Western intelligence agencies. Studies have suggested that China is building fields of new missile silos in its western desert regions. The Federation of American Scientists, which identified the silos via satellite imagery, described them as, “the most significant expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever.” This also suggests a shift in China’s nuclear posture, which had previously been based on the principle of “minimum deterrence,” a policy in place since China detonated its first bombs in the 1960s. This policy entailed keeping its arsenal at a minimum level necessary to deter an attack. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that China has around 350 nuclear warheads, a fraction of the 5,550 possessed by the United States and the 6,255 by Russia. However, this stockpile is rapidly growing, and the Pentagon predicts the number of Chinese warheads will at least double in size over the next decade. Understanding China’s nuclear stance, especially with tensions soaring over Taiwan, has become increasingly important to Western analysts, but especially difficult because Beijing has rebuffed American suggestions for a nuclear dialogue.

The confirmation of the shake-up at the top of the rocket force coincided with intriguing comments from CIA director William Burns that the United States is making good strides in rebuilding its spy networks in China, which were heavily compromised a decade ago. The years between 2010 and 2012 were particularly difficult for American spies in China, with dozens of sources reportedly killed or disappeared. “We’ve made progress and we’re working very hard over recent years to ensure that we have strong human intelligence capability to complement what we can acquire through other methods,” Burns told the Aspen Security Forum. Whether the timing was coincidental, or whether there was an element of gloating is hard to say, but the comments certainly touched a raw nerve in China. Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said, “China will take all necessary measures to firmly safeguard our national security.” Chen Yixin, the Minister of State Security, has said that China must “severely crack down” on those who might steal China’s state secrets.

The PLA used to run its own businesses, and there was a time when money making seemed to be a higher priority for it than preparing for war. Corruption was deep-rooted. Cleaning up the military and instilling loyalty to him and the party were Xi’s key priorities when he came to power in 2012. They were seen as prerequisites for turning the PLA into a more modern and professional fighting force. The latest purges suggest this is still a work in progress.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.