Ask three different people whether Russian President Vladimir Putin will approve an invasion of Ukraine, and you are likely to get three different answers. Yes, a Russian land, air, and sea blitz is inevitable and will come in fairly short order, likely without warning. Yes, a Russian invasion is possible, but could still be averted with some shrewd diplomacy. Or, no, surely Putin understands an invasion would be a disaster for his legacy and his country’s economy.

In the midst of all of this comes wild speculation about what Putin is thinking at any given moment, how the weather may factor into his calculations, and what the Russian government’s end goal really is.

What can be said for certain, however, is that diplomacy has picked up significantly over the past week. The aim: to find an off-ramp that would allow Europe to escape what could be the largest conventional military operation since World War II. The only issue is that the talks are moving at a snail’s pace, and nobody can tell with certainty when (or indeed if) Putin’s patience will run out.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s trip to Moscow last week, when he spoke with Putin for over five hours, produced little more than confusion over what was said. After the meeting, Macron’s aides boasted that Putin had agreed to refrain from any new military action for the time being, a suggestion promptly dismissed by Putin’s chief spokesman.

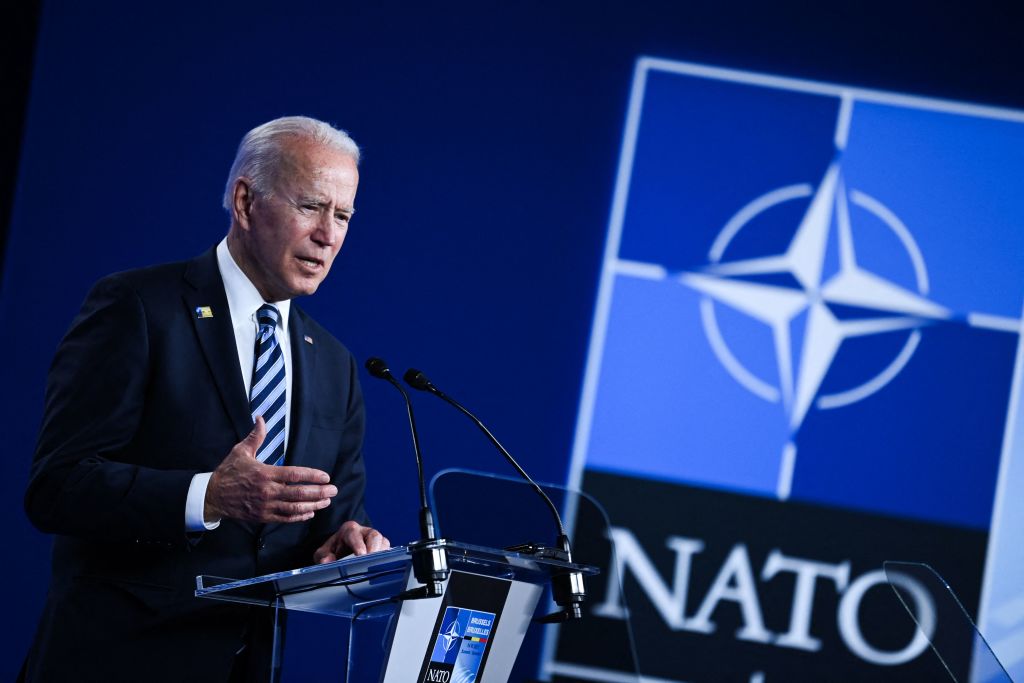

British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss flew to Moscow for her own talks with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, which for all intents and purposes was nothing more than a sanctimonious airing of grievances. President Biden spoke with Putin over the phone for an hour on Saturday, but this too resulted in nothing substantial (“There was no fundamental change in the dynamic that has been unfolding now for several weeks,” a senior administration official said). German Chancellor Olaf Scholz jetted to the Russian capital today.

All of these conversations come as news emerges of Russian forces redeploying some of their forces away from Ukraine’s border. Still, the Biden administration clearly doesn’t believe the Russian invasion threat is a bluff. Appearing on Face the Nation over the weekend, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said Putin has the forces, equipment, and military enablers in place to order an operation “this coming week.”

The US embassy in Kyiv is temporarily moving its operations to Lviv, and US officials have been screaming for days that Americans in Ukraine should get out of the country. The European Union, Britain, Germany, Canada, and Lithuania (among others) are paring down their embassies and advising citizens to leave. America and its allies in Europe are at the point where they are hoping for the best but preparing for the worst — and the worst, according to US intelligence estimates, is a Russian thrust into Ukraine that kills tens of thousands of civilians and pushes millions of refugees into Poland and the Baltics.

Of course, preparing for the worst is what responsible policymakers do. It’s the “hoping” that is troubling.

While it’s true that the US and Russia are at least sending proposals to one another about mutual security arrangements related to missile inspections and military exercises, Washington is still hoping Russia will blink on its core demand: Ukraine being iced out of NATO and the alliance shelving any further enlargement in the post-Soviet space. Russian gripes about NATO enlargement, however, have been a regularity for more than three decades. The NATO expansion issue didn’t come out of thin air, nor is it an obsession unique to Putin. Every Russian head of state since the fall of the Soviet Union has been on record opposing the idea of NATO pushing further east — even Boris Yeltsin, the closest person Washington ever had to an amicable Russian president.

The only difference between then and now is that, unlike the pathetic and hollowed-out Russia of the 1990s, the Russia of today can actually utilize the military power at its disposal to prevent further expansion in nations (like Ukraine) it deems off-limits. Commentators in the West can moan about this development, but it doesn’t change the underlying fact. Even autocratic powers can have security concerns.

The one proposal the US could offer to defuse a potentially disastrous war is to foreclose the option of Ukraine joining NATO, possibly through a moratorium, in exchange for a Russian troop withdrawal from Ukraine and an end to support for the separatists. Yet Washington and Brussels adamantly refuse to consider this. The hesitancy is due to a variety of factors, including reflexive opposition to anything that might be construed as a concession and a utopian belief that all states have an inalienable right to choose their own alliances. Unfortunately for the utopian crowd, the balance of power matters in international relations — and Europe, like it or not, won’t be stable until some of Russia’s concerns are mollified.

NATO isn’t going to bleed for Ukraine. Formalizing this reality is a small price to pay if it means sparing Europe a war.