Like a priest standing before the bronze gates of a temple, the British ambassador to Washington serves as the guardian of one of the great modern myths: the idea, conceived by Winston Churchill, that a special relationship exists between the UK and the US. The impression that British ambassadors can wield disproportionate influence in Washington is a legend successive British governments have been eager to burnish – so much so that it has arguably become the central pillar of UK foreign policy since 1945. But the reality – as Donald Trump’s spectacular defenestration of Sir Kim Darroch shows – is rather different.

Perhaps only one ambassador has really ever lived up to the myth. During the 1960s, David Ormsby-Gore, later Lord Harlech, enjoyed extraordinary access to JFK, a family friend who had asked Macmillan to post him to Washington.

From this privileged position, Ormsby-Gore was able to provide unmatched insight to London and it is to him that we also owe the early description of Kennedy’s populist successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, as ‘one of the most egotistical men I have met’.

This was, the British ambassador said, a man who ‘likes low interest rates’, ‘has little interest in the history or affairs of other countries’ and ‘hardly ever reads’ a book, for whom ‘the frustrations…of supreme power are less than the frustrations of not having supreme power.’ It is a sign of how sensitive such pen portraits are known to be that the Foreign Office only agreed to declassify it 10 or so years ago, even though Johnson had died in 1973.

Secrecy is central to the maintenance of the myth and the British had guarded the temple gates zealously until the recent leaks. The Foreign Office admitted a few years ago that it retains over a hundred meters-worth of files concerning the United States which it refuses to declassify, even though they are no longer covered by the 30-year rule. It is best not to let too much light in on the magic.

Yet relations between London and Washington are not – and have never been – as special as Churchill would have liked. In 1951, once Churchill was back in Number 10 and ahead of a meeting with Truman, the American ambassador sent a character assessment back to Washington. The prime minister, he warned the president, was ‘definitely aging’. He was ‘increasingly living in the past and talking in terms of conditions no longer existing. These developments in his personality mean that he is more difficult to deal with.’

The State Department, incidentally, did not treat that delicate assessment of Churchill’s senility with anything like the caution the Foreign Office treated Ormsby-Gore’s pen-portrait of Johnson. It was published in the widely available Foreign Relations of the United States series, in 1977. So much for a special relationship.

Truman evidently took on board Churchill’s nostalgia, but managed to give him the most marvelously insensitive present. This was a photograph from the 1945 Potsdam conference. Since the photographer had been standing behind Churchill, Truman dominated the picture. All that could be seen of his British counterpart was the bald spot on the back of the prime minister’s head. ‘Truman was quite abrupt…with poor old Winston,’ wrote one British official who witnessed the meeting. ‘It was impossible not to be conscious that we are playing second fiddle.’

The British were delighted when Eisenhower became president. But when Churchill put the idea of a special relationship to Ike, Ike was unconvinced. In his diary, he described Churchill’s faith in such an arrangement as ‘almost childlike’, and dismissed it: ‘any hope of establishing such a relationship is completely fatuous’.

The problem was that, while Churchill was proposing a partnership of equals, Britain was grossly indebted to the United States and clearly entering a period of rapid decline. The evidence nourished Ike’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles’s skepticism about the people he referred to as ‘our cousins’. ‘He had absolutely no regard for them internationally,’ recalled one of Dulles’s advisers. ‘He felt that they were being clumsy and inept, as opposed to their carefully nurtured reputation of being the opposite, and he…had no admiration for them.’

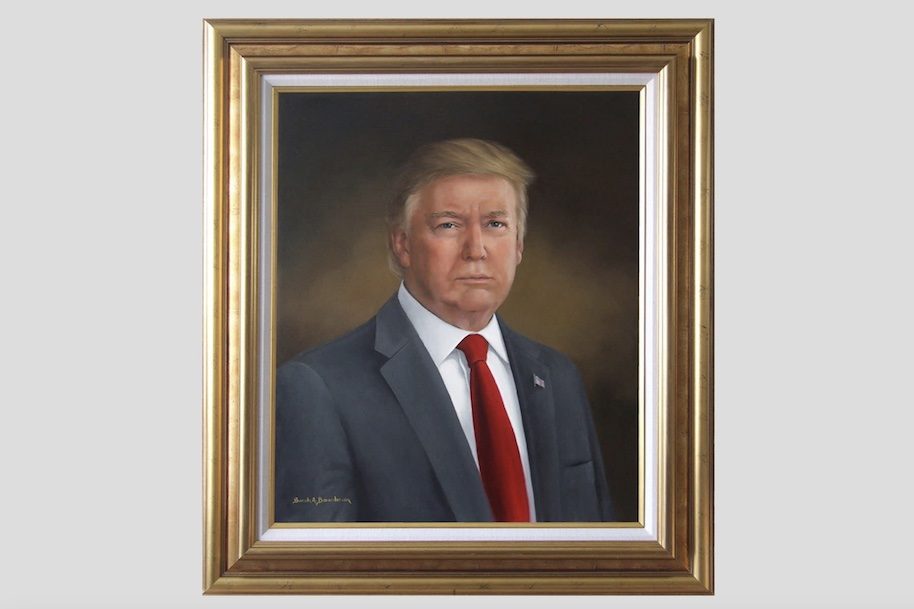

It is a peculiarly British triumph, of sorts, that the idea of the special relationship has survived despite the evidence to the contrary piling up on the American side. It may struggle to survive the splenetic tweeting of the disinhibited incumbent of the White House, however.

That matters, and not simply because it might dent our pride. The presence of what Macmillan called the ‘special Atlantic “super scrambler”’ at arm’s length on his desk in Downing Street has not simply been a comfort as London’s power relative to Washington’s has waned; we have used it to persuade many other countries that we matter. And that is what makes Donald Trump’s announcement that he will ‘no longer deal with’ Sir Kim Darroch – who is an honorable and decent victim of this row – so bad.