Donetsk

It’s past midnight and I am standing in silence with the crew of a military ambulance on the edge of the Donetsk region. The village is dark to avoid attracting the attention of Russian drones. The paramedics move with quiet determination, lifting blood-soaked stretchers and ferrying moaning, injured soldiers from one vehicle to the next. I see a wounded man with bandages where his legs used to be. His severed limb sits next to him in a bag.

There are no figures for how many Ukrainians have been maimed in this war. Nor are there proper figures for the dead. Kyiv doesn’t give body counts, saying only that Ukrainian casualties are “ten times less” than Russia’s. Keeping the numbers secret prevents scrutiny. The US estimates that at least 17,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed in action. Another official told the New York Times the number could be as high as 70,000.

Many of those lost in the war die while they are being moved back to safety rather than on the front line

I am told by those working here that many of those lost in the war die while they are being moved back to safety rather than on the front line. The long journeys to hospital, sometimes up to ten hours, can be lethal, and the availability of adequate first aid is the difference between life and death.

Ukrainians believed that the very best care would be available for their soldiers. But the stark truth is emerging: soldiers are dying in their hundreds or even thousands due to poor medical provision. The problem is being ignored by the military hierarchy, whose focus is on sourcing weapons and pushing the counteroffensive rather than prioritizing injured fighters.

Word of this has spread, and Ukrainians are responding by donating to independent medical units serving on the front line. I’m with one such group, the Hospitallers. It is a Ukrainian volunteer medical battalion that works closely with frontline troops.

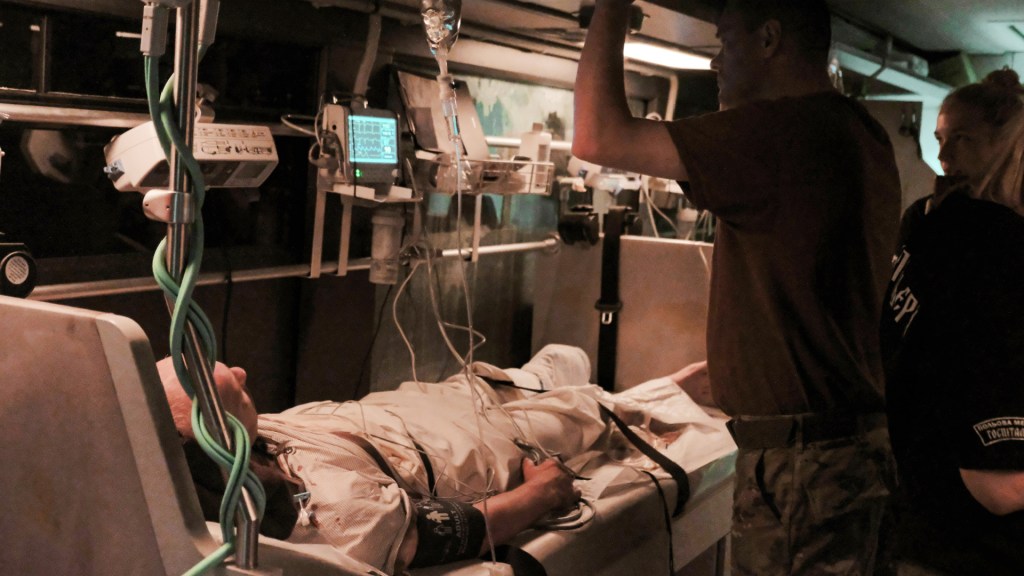

I see the Hospitallers take in six injured soldiers who have been handed over to them by combat medics. These men were hurt about five hours ago; it then takes four more hours to get them to the hospital in Dnipro. “This is a fight for life. Our task is to keep them going until they reach the hospital, to help them survive. Once there, they will receive more advanced medical assistance,” explains twenty-eight-year-old Toronto, a paramedic. I ask him who would be rescuing these soldiers were it not for the Hospitallers’ volunteers. “Nobody,” he replies.

Ukraine has mobilized more than half a million people into the military, and it badly needs tanks and aircraft for the war effort. This message is the one Ukraine’s allies have received: give us the tools, and we will finish the job. But there is also a far less publicized but no less urgent need for medical aid, including for vehicles to transport the injured to hospitals.

The bureaucracy surrounding the first aid process is to blame for many of the shortages. If a hospital vehicle is destroyed by enemy fire, it is not registered as being out of action until an official investigation has been carried out. This can take up to six months. Until the paperwork is done, the vehicle stays on the books and is not replaced. It’s common to find military brigades that have lost 80 percent of their evacuation transport, but that can’t be resupplied because the official report does not acknowledge that the vehicles have been destroyed.

As a result, volunteers are taking matters into their own hands. I’m shown around Avstriyka, a $125,000 mobile hospital bus, funded by donations. It is a unique unit which can carry up to thirty-three soldiers, with six on stretchers.

One of the paramedics I meet is an American volunteer, thirty-four-year-old Victor Miller, who served in the US navy and last year joined Hospitallers. “If you have it within yourself to go and do something and help people, you should do it,” he tells me. “It’s only a matter of time till the war moves past Ukraine.” He talks about the shortage of medics and says far fewer foreign volunteers are there now than there were last year: “We had fifty. Now we have fewer than ten foreign paramedics.”

Another problem is that corruption has been allowed to flourish. One example is the proliferation of low-quality medical supplies being used to treat Ukrainian soldiers. A few weeks ago Volodymyr Prudnikov, the head of Ukraine’s Medical Forces Command’s procurement department, was accused of supplying 11,000 uncertified Chinese tactical medical kits to the front line. It is alleged that Prudnikov awarded $1.9 million-worth of contracts to a company co-founded by his daughter-in-law and was attempting to pass the Chinese kits off as NATO standard. He has been fired and now faces an investigation, but has yet to comment.

It is just one example of the profiteering that is needlessly risking the lives of soldiers. Another example of corruption occurred last year in Lviv, where 10,000 tactical first aid kits worth $880,000 were sent by American volunteers and then mysteriously disappeared. It was recently reported that the US is investigating this case.

‘The military leadership can refuse to accept supplies because they are fully stocked with low-quality alternatives’

More questions arise when it comes to the contents of the first aid kits that do make it to the front line. Tourniquets are perhaps the most-needed first aid tool, particularly when the evacuation process is prolonged. But if tourniquets are badly made, they can be lethal. There have been complaints from the front line about Chinese-made tourniquets that either gradually lose pressure or come apart, leading to renewed bleeding with fatal consequences. A Chinese tourniquet costs just $2.50, while a Ukrainian “Sich” tourniquet is $19. An authentic American CAT tourniquet comes in at around $44.

Investing in decent tourniquets is money well spent. The medics I speak to say that two-thirds of Ukrainian soldiers die from blood loss. I meet twenty-four-year-old Bilka, a medic in the 243rd Territorial Defence Battalion, who has just returned from Bakhmut. She explains what happens to the injured person on the front line: “You have to drag a person with your hands approximately three to five kilometers. You can’t drive there even in armored vehicles because of the heavy shellings and mines.”

Medics, she says, try to avoid using the official first aid supplies issued to them, because of the admin that is involved. Each component of a government-issued medical kit must be accounted for, including equipment that is obviously sub-standard. “If a drug has expired, the write-off procedure is so difficult that it is easier to record that it has been destroyed by fire,” she says.

Some medical staff are funding equipment with contributions from their own salaries even though the average doctor in Ukraine only earns about $380 a month and a nurse half that sum. The situation has become so bad recently that medics at one hospital in Dnipro, which was overloaded with injured men from the front line, had to raise money to buy antibiotics, analgesics, gauze and even gloves needed for treatments. Meanwhile some $4 billion a month is spent on warfare.

I also talked to Yuri Kubrushko, the co-founder of the Leleka Foundation, another medical charity. He says that the surprise full-scale invasion last year was always going to mean there would be a shortfall of proper medical supplies. But eighteen months later, the situation still hasn’t improved. “The problem with providing equipment to combat medics is being hushed up as if it doesn’t exist,” he tells me. “The military leadership can even refuse to accept new medical supplies because they are fully stocked with low-quality alternatives. They think that asking charities for help would undermine the authority and reputation of the armed forces.”

When it emerged that 15 percent of medical supplies donated by the West last year had passed their expiry date, it led to public outcry and criminal prosecutions. Officials from Ukraine’s Medical Forces responded by saying they would inspect all medical kit in the army. But no guidelines or standards for these inspections have been issued. Senior officials in Kyiv do not seem prepared to complain, or bothered enough to do thorough checks before sending the first aid kits they receive on to the front line.

“The leadership of the old establishment doesn’t truly understand what is wrong,” says Kubrushko. Inspections are no use if the people commissioned for the task have no idea what to look out for. “They won’t suddenly become tactical medicine specialists just because an order came from above.” As a result, reports are tinkered with, which in turn distorts the statistics on how much medical aid is required. Why should Ukraine ask for more medical equipment, when officially the shortage doesn’t really exist?

Tetyana Ostashchenko, the commander of Ukraine’s Medical Forces, has said in an interview that the problems Ukraine faces have no precedence in modern times. No western country has experienced what Ukraine is going through. Two weeks ago, Ostashchenko was given a final warning and ordered to undertake an inspection of frontline equipment, but the promised report has yet to materialize. “If the criticism is constructive, then of course our reaction will be immediate,” she says.

To compound the problem, medics in Ukraine are also expected to fight. “You can’t sit and say, ‘I’m a medic, I won’t shoot.’ Everyone shoots. Only after the fighting is carried out, then you provide the first aid,” says twenty-seven-year-old Gurman, a senior combat medic with the 243rd Territorial Defense Battalion.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, combat medics sent out to rescue injured soldiers under Russian fire often lack both the training and the authority to deliver aid. Some have a medical background, but most must learn in the field, usually at the front line. A senior combat medic will teach junior members. In the whole of Ukraine, only one military base is capable of providing an official qualification for a “junior medical personnel.” That base turns out 300 medical cadets a month, but to allow for one medic for every thirty soldiers, Ukraine needs to train at least 15,000 combat medics. There are various private training centers which devise methods as they see fit.

The UK has so far trained 17,000 Ukrainian soldiers since last February, some of whom are medics. But all too often they are used to working with a standard of kit that is unavailable in Ukraine, and the training is not tailored to the war that is being fought. Gurman was trained in York. He tells me about the arguments he has subsequently had with his instructors. “The medical course is focused on gunshot wounds. But in Ukraine, soldiers are being blown apart. You need to piece a whole person together,” he says.

Russian attacks target Ukrainian medics as a priority, he adds. “If Volodymyr Zelensky was in a car and we were sitting in a car next to his, they would hit us first, because we save lives.” Russian forces use drones to track medical vehicles and then fire at them. Ukraine’s military medical institutions have seen over 1,000 attacks since last year’s invasion.

Russia is, of course, responsible for the lives lost in this war. But it seems undeniable that the Ukrainian authorities’ neglect of the medical necessities is leading to a far higher death toll.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.