What would Adam Smith think of cancel culture? Many advocates of banning books now hide behind a veil of free-market purity: If Amazon bans a book, it’s not really banned because the online megalomart is, a private company. But it controls an outright majority of book sales in the United States, and even that remarkable measure may underestimate the power Jeff Bezos’s company wields over individual titles. Bestsellers can be found elsewhere perhaps, but most books have few other outlets.

So Amazon doesn’t ban books. It just makes them much harder to buy and read. If a private company chooses to do that, who are you to complain? If you’re a reader, you’ll just have to hunt elsewhere — though you might find other large retailers, such as Walmart, have adopted the same corporate censorship policies. If you’re the author or publisher of a megacorp-disapproved text, you still have nothing to complain about: can’t you always start your own bookstore?

As I write, that’s thankfully not necessary for one Amazon-canceled book: When Harry Became Sally, a critical look at transgenderism by Ryan Anderson of the Ethics & Public Policy Center in Washington DC. It hasn’t been suppressed everywhere. But you can’t buy Anderson’s book on Amazon — at least not anymore. It was published in 2018, and until February of this year Amazon saw no grounds to withhold it from the reading public.

What changed? Amazon doesn’t say. A private company owes no one an explanation, as far as Bezos and his thought police are concerned. Walmart’s website offers a wide selection of books, including others by Anderson, but not When Harry Became Sally. Thank God for Barnes & Noble, who deserve the thanks of all who still believe we should be able to read what we want, not just what the nannies and commissars of corporate America deem fit for our eyes.

And if Barnes & Noble goes bankrupt or succumbs to the censors? Doesn’t matter — just start another bookstore chain. Fine idea, except that businesses, and not just books, are getting canceled by Big Tech. Parler, for example, was an attempt to start a new social network. Conservatives feeling smothered by Twitter’s abridgments of political speech were willing to overlook Parler’s technical inadequacies, so eager were they for an alternative. The business found a niche. But Big Tech’s market-dominant players decided to snuff out the upstart they could not control.

After Twitter banned Donald Trump, Parler rocketed to the top of the download charts on Apple’s app store — until Apple abruptly removed it from sale. Parler tried to carry on, so Amazon booted the defiant social network off its web servers. The lesson was clear: if you adopt free-speech policies that the tech titans dislike, they will converge to shut you down and shut you up.

Adam Smith staunchly defended private enterprise, but he warned in The Wealth of Nations that ‘people of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.’ The tech companies that control and constrain online communications in the United States are indeed ‘a conspiracy against the public’, not to raise prices — though that warrants a closer look — but to impose their politics and morals on everyone.

Monopoly is not the relevant category here. The Big Tech cartel is not the sole purveyor of its products, but its members have such a dominant position in online communications as to threaten both individual liberty and open public discourse. Even the most traditional medium of First Amendment freedoms of the written word, the newspaper, is now a creature of the tech cartel, as Google controls the web advertising on which for-profit print publications depend. Jeff Bezos’s ownership of the Washington Post is an apt metaphor for the relationship between the tech oligarchy-oligopoly and the press as a whole.

Breaking up the tech companies might not be the answer, however: a cartel with a dozen members can be just as ruthless as one with only five or six. When all the players follow the same politicized hiring, management and human-resources policies, their intuitive collusion is self-reinforcing: to be canceled by one tech giant is to be blacklisted by all.

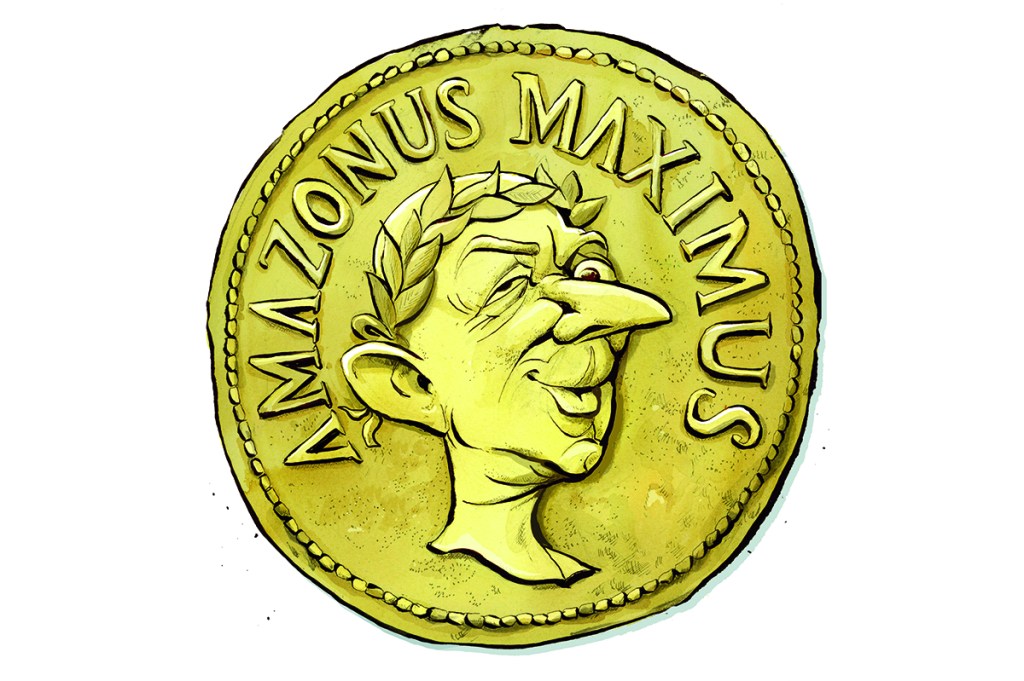

Big Tech does not truly compete. This poses a problem for conventional economic thinking: such non-competition has a psychological aim rather than a commercial one. The tech cartel has the private business world’s freedom from public accountability, yet it commands more wealth than whole nations and has a singular chokehold on published speech in the US. All this unchecked power serves a moral vision as comprehensive as that of any religion. For Big Tech, as for religions of old, error has no rights. And the public has no right to know or debate anything — not on Lord Bezos’s estate.

The Democratic party benefits politically from the suppression of speech online and the privileging of a single ideological point of view. Yet it is far from certain that Republicans understand what is required to restore the intellectual commons. There’s an obvious contradiction between GOP complaints about censorship and calls on the right for stricter libel laws and new ways to sue tech companies for what gets said on their platforms.

But if policy remedies are elusive, the cultural prerequisites of the cure are not: Americans must understand that their freedom to read what they choose and to think for themselves is opposed by an ideology that calls itself progressive and liberal, and by a concentration of unaccountable power over the tongue and mind unlike anything this country has encountered before. A new philosophical critique of this power and of the commissars who wield it must be devised, a critique as radical as the thought of Adam Smith was in 1776.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.