Is there hope for literature in America this century? The forecast looks grim. One walk through the literary fiction section at a bookstore is a testament to the art form’s cultural bankruptcy. Just about every other book on the new release table is a treatise on your racism masquerading as a tale of collective uplift. Fine, if you want to expiate your sins of privilege – but all in all, a snoozefest.

Novels held a central place in America as a vital cultural force; novelists were worshipped as electrifying sages

Same goes for most of the books on the New York Times list of the 100 best books of the century so far. The subjects of race, gender and oppression generally dominate. Soap-opera conflicts about victimhood crowd the rankings, each one a reproach against your unspoken crimes: your whiteness, your maleness, your very existence. Narrow and righteous, this is a fiction that cannot be pulled apart from politics. Like the top-ranked sermons of Protestant ministers from the 1800s, the whole lot will slide into irrelevance, unread and forgotten.

The poet Joseph Bottum once described to me what he calls a “cocktail party test” to gauge the cultural significance of a novel. The test is to ask whether you would feel any embarrassment if the smart set at a party brought up a new book and you had to admit you hadn’t read it yet.

With TV shows, this still happens. The hit HBO series The White Lotus even satirizes such conversations, itself being a show everyone wants to share and talk about after an episode airs. Bottum suggested that the last novel to pass this test was Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, published nearly 40 years ago in 1987, a hard-to-believe time when novels still held a central place in America as a vital cultural force and novelists themselves were worshipped as electrifying sages by obsessive fans. The whole country talked about Bonfire. Not just an insular claque of corpses at New York publishing houses and magazines.

Americans simply don’t read so-called serious fiction very much anymore. Particularly men. It is worth asking why.

In a column this summer in the New York Times, David Brooks picked up the question, lamenting the fading glory of the literary novel. He too brings up Wolfe as one of the last great American novelists, along with a host of other big names in a Macy’s Parade of boomer nostalgia. Look there’s Saul Bellow! And Philip Roth and Toni Morrison! See how they elevated our souls! Such passionate and prophetic voices, but now, alas, the parade has been canceled, the crowds dispersed and the children told Santa was never real. They might as well look at their phones.

It is true, Brooks concedes, there are fine novelists out there toiling in the fields of obscurity, but he says they have all failed to capture the whole public’s imagination because they play it too safe and too small. He calls for – begs for – novelists with a grand enough ambition to capture the zeitgeist, to show us who we are – all of us, not just some – and what we could become. Only then might America start reading again.

It’s a rousing thought, for sure, a heady enough cocktail to quicken the pulse of the most indebted English major’s heart. At least for ten minutes before the next student loan payment comes due. But I’m not convinced that the future of literature in America is dim for lack of courage. The rot is much deeper than that. The poor, sad death of the Great American Novel has less to do with the lost virtue of aspiring writers and more to do with the erosion of a unified national identity and the country’s consequent trajectory toward a more fragmented society of different competing cultural tribes.

These divisions in the US are deepening: boomers versus Generations X, Y and Z; urban versus rural; race communists versus conservatives; even regional differences are intensifying, with states such as California and Texas growing further apart in policy and culture. It’s hard to believe even a novelist of the first rank could appeal to all members of these warring factions.

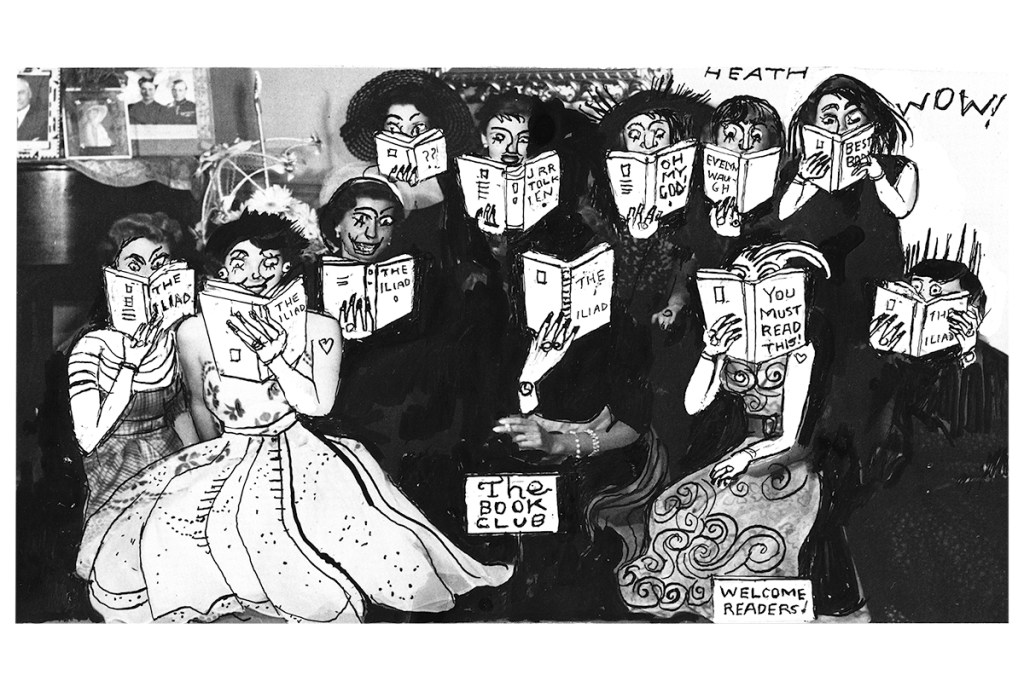

But while it’s true the mainstream literary beast lies belly-up, gasping for its last breath, something fervent is stirring in the cultural underbrush. There may never be a single novel that dominates conversation at cocktail parties across the nation again, but there are little polities of the mind emerging, building their own canons like medieval monks illuminating manuscripts in hidden scriptoria.

Take the TradCaths. This small but spirited tribe is resurrecting G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, J.R.R. Tolkien and Evelyn Waugh – not American authors, sure, but they will form the foundation of a counter-canon that’s booming in sales of reprints and in homeschool curricula, while the secular slop of literary fiction wheezes on life support. In short, the center cannot hold, but the fringes will flourish. And there is one niche with a strong counter current that interests me most.

One of the oldest themes in the western canon is the conflict between greatness and prestige. What might roughly be called the hero versus the king. The very first word of The Iliad is an ancient Greek word for anger, but not just any anger. It is intense and divine and it is the fury of Achilles, the best among all the heroes in the field.

One of the oldest themes in the western canon is the conflict between greatness and prestige; the hero versus the king

And even though the Greeks are at war with the Trojans and have been for years, Achilles isn’t angry about that. He’s angry because an incompetent, corrupt, but legitimate king, his ruler and commander, has taken what doesn’t belong to him. So Achilles shrugs. In a huff he retires from the battle. The central conflict of The Iliad isn’t between the Trojans and the Greeks. It’s between Achilles and Agamemnon: the hero versus the king.

There are two types of hierarchies battling it out in America today: the hierarchies of prestige and the hierarchies of greatness. They have very different cultures. Prestige hierarchies are those institutions that have a long history, that are large, bureaucratic and powerful and that form the establishment – the departments of the Federal government, Wall Street banks, the media, the professions and elite universities.

Hierarchies of greatness, on the other hand, emerge when something is the best at what it does in a competitive landscape. They have a short history, they are small and they are extremely competent. A clear example is SpaceX compared to NASA. One soars; the other is buried in committee meetings and memoranda.

In the hierarchy of prestige, advancement and promotion depend on pleasing superiors. To ascend this pyramid, you must have the right opinions and know the right people. In the hierarchy of greatness, to ascend you must win and solve problems. It’s not about who you know or impress, it’s about what you can do.

The literature of prestige is the literary canon of the pyramid-climbing tournament that has gripped the nation for 50-plus years – that is, the elite college admissions tournament and beyond that, the tournament to enter the professions and civil service.

The character-stripping rules for advancement in this pyramid anesthetize genius. Genuine artistic geniuses do not go to grad school, where conformism, collusion and incrementally becoming a toady are all rewarded. This pyramid molds a nation of diligent functionaries, time servers and careerists who don’t want to rock the boat. The table of new novels at the bookstore, the New York Times list of the 100 best books this century, contain the books you must read to advance within this world.

For the hierarchies of greatness, it isn’t the professor or the critic or the journalist who makes a literary canon, but the builder or artist. Membership is determined by those who create.

Among this crowd, there are books discussed as passionately at Silicon Valley house parties as French poets brawling over aesthetics in a Parisian café: The Diamond Age by Neal Stephenson, The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes, The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch.

Meanwhile, the established, respected, highbrow world of literature, the gatekeepers to the professions and the petty tyrants of the administrative state read their canon on a sinking Titanic.

The future of American fiction is not in New York’s publishing houses, nor in the pages of the New York Times. It’s tribal and alive in the shadows, where stories are written not for prestige but for truth. It will belong to those who win.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply