‘Labour are in so much trouble here you can’t even believe it,’ says Nigel Farage as we sit in a parked blue bus in Dudley, West Midlands, in the pouring rain. Outside, a group of campaigners in anoraks wave Brexit party banners and sing ‘Bye bye EU’ to the tune of ‘Auld Lang Syne’. A mix of locals and supporters from out of town have assembled to hear Farage. A Japanese camera crew rush to film the circus around him. Reporters from New York are following the pack. Keeping up with Farage is exhausting.

When Farage was last in Dudley, the town went on to vote overwhelmingly to Leave, by 67 percent. Back then, he tells those assembled, the sun was shining. The change in weather, he says, reflects the change in our politics. The story he now has to tell is as much of humiliation as betrayal. Brexit was meant to be a moment of hope, but instead has become a national embarrassment, he says, and it’s time to do something about it. The crowd — made up of a mix of traditional Labour and Tory voters — goes wild as he calls for a no-deal Brexit and asks: ‘Are we going to be a great independent self-governing nation?’ Yes, comes the loud reply.

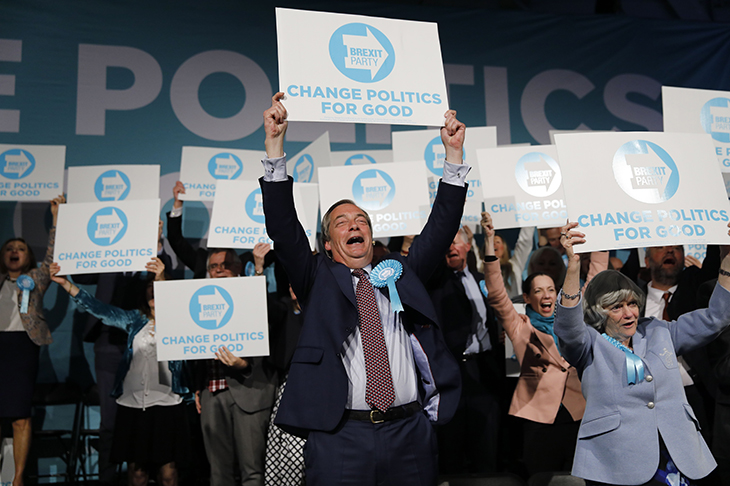

Farage has been making speeches like this for the best part of two decades, yet his latest project has a reach far beyond what Ukip ever had. Before the Brexit party’s launch last month, he placed a £1,000 bet that it would finish in first place in the European elections. Since then it has defied all expectations — surging in the polls, packing out venues across the country and going viral on social media. It is now polling first in Wales and ahead of Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives in Scotland. Barring a major upset, the party is predicted to come first by a comfortable margin when the votes are announced on Sunday. The big question: what next?

Farage is keen to quash suggestions that support for the Brexit Party in the EU elections can be dismissed as a protest vote: ‘We’ve already won this battle once and it’s been denied us so people have made the connection in their minds that the problem isn’t winning a Brexit vote, the problem is getting a political system in Westminster that is prepared to reflect that view’. The threat the Brexit party poses to the Conservatives has been well-documented. One poll suggests that most Tory councillors — let alone voters — will go with Farage. He hopes to pose as great a problem to Jeremy Corbyn by targeting the millions of Labour supporters who voted Leave and have since been left alienated by the party’s ambiguous stance on a second referendum. ‘This is about breaking the two-party system,’ he tells me. ‘It’s about massive political change in this country. It’s about getting Westminster closer to the people.’ But what about his getting closer to Westminster? ‘It’s very difficult to break through in first-past-the-post politics. I know that more than any human being alive. Here I am again, I mean I must be off my rocker.’

After standing for Westminster seven times in 25 years without success, Farage can speak with authority about this. People who had voted Ukip in the European Parliament elections then went back to their old party. ‘They’d lend their vote to Ukip in a European election thinking “well I’ve said what I think and that’s great and then at the general election I can go back to voting for the same party my grandad did” because that’s how tribal that allegiance is. But this is different,’ he says. ‘A lot more people now are saying: “No, no, we’re going to stay with you all the way through”.’ In the 2015 election, Ukip got nearly four million votes but only one MP — paving the way for a Tory majority. But Farage is certain the Brexit party would be far more successful: ‘I believe that if there was a general election in the next few months, the Brexit party would get a lot more than four million votes.’

Dudley North, which Labour held by a majority of just 22 votes at the last election, is one of the Brexit party’s better hopes. The crowd I meet are fed up. One lifelong Labour voter, Sharon, says she won’t be backing Corbyn any time soon. ‘I’ve always been a Labour supporter in the past. But when I voted Out, it was my opinion it meant Out. We’re not being treated fairly.’ The Brexit party MEP candidate Martin Daubney, a journalist, is aiming at voters like her. A coal miner’s son, he says he thought he would ‘die Labour’ but concluded that Ed Miliband’s leadership was final proof that the party followed a metropolitan agenda and ‘abandoned the working classes’. He believes more Labour voters are deserting the party. ‘We’ve been betrayed and as a consequence now we have this scorched earth. And the opportunity is rampant. Talk to people around here and they are disaffected Labour, disaffected Tories. All abandoning their parties after lifelong membership and commitment.’

At any Brexit party rally, you can see little trace of Ukip — or the man who once said the UK should reject migrants with HIV. Even immigration is barely mentioned. Instead the narrative focuses on a betrayal by Westminster and the need to protect democracy. And, also, the variety of supporters: alongside the likes of Ann Widdecombe and Annunziata Rees-Mogg you have candidates such as Claire Fox, a former member of the Revolutionary Communist Party, who is as surprised as anyone to be in the same party as Farage. But that’s the Brexit effect.

At a packed rally on the outskirts of Bolton near the local football stadium, Fox is awarded a standing ovation with a speech to ‘plumbers and philosophers’. She finishes with a quote from Tony Benn. Attempts by Labour to paint the Brexit party and its supporters as extreme have backfired, she tells me afterwards. ‘One guy just said to me: “How dare they. We’re anti-racist, we’re traditional Labour voters. That’s why we are in the Labour party. Then to have our own party label us that.” In a way that’s a kind of double betrayal.’

All of this is easy — for now. But once the political discussion moves beyond Brexit, how could a former Marxist like Fox and a Thatcherite like Farage stay in the same party? Farage has given a few hints as to a broader policy platform: scrapping HS2, for example, or scrapping the BBC license fee. There are some issues that could unite left and right — but enough to fill a manifesto? It’s unclear. For now though, Farage’s £1,000 bet looks pretty safe.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.