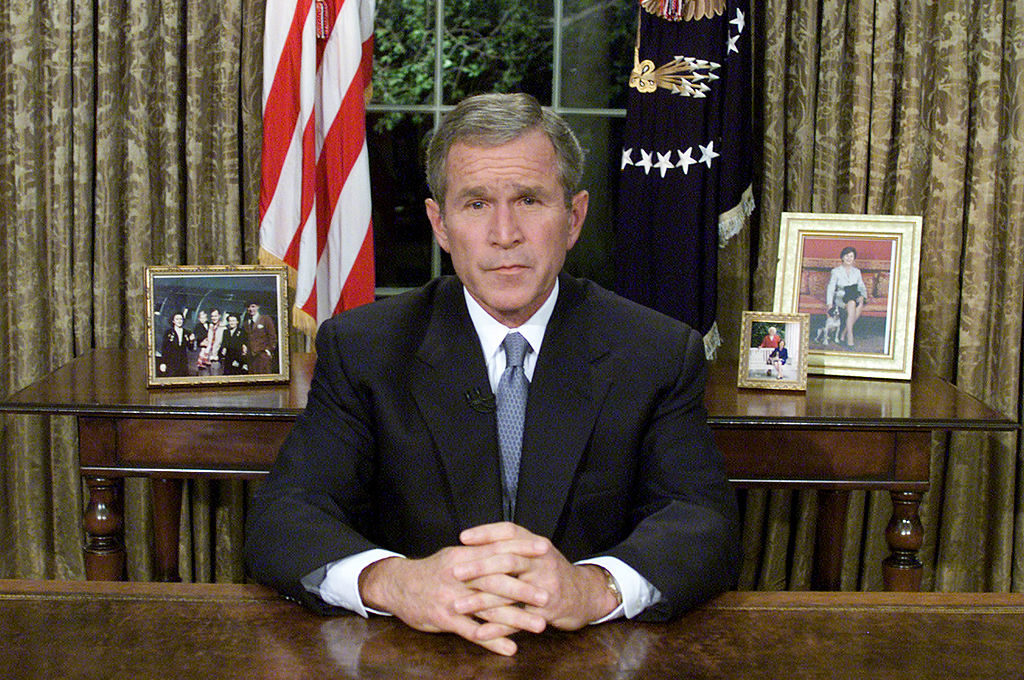

Justin Raimondo is dying. It’s October 2018 and I am headed to the ‘Raimondo Ranch’, in Sebastopol, northern California, to visit the home of the founder of Antiwar.com, the cult website that kept the faith in the early days of the net as Bill Clinton mindlessly bombed Yugoslavia, and George W. Bush leveled Iraq. No one cared, of course. And everyone else was wrong.

Raimondo is a legend. The ‘ranch’ is no paleoconservative plantation. It’s a quaint shack with a garden that looks like it’s used to grow marijuana, but charmingly probably isn’t. The property will go to Yoshi, who Raimondo describes as his boyfriend, though in fact the pair are married. Raimondo wouldn’t like such talk: if you want a spouse, get a wife, seems to be his sentiment, but he will bend the knee for those he loves.

Raimondo cuts an ascetic figure: wiry, chain-smoking, dressed punky but plainly. His reputation is the same to friends and enemies: warrior-monk and asshole.

There is no God, Raimondo says. This is it; this is all there is. ‘My country’s fucked up,’ he tells me, through tears. Time is short.

Back to the house: it’s prime real estate, nestled in the more remote part of the famed Russian River Valley. It’s wine country, but Raimondo doesn’t drink. Good thing he did everything else with his life.

*

Justin died, finally, on June 27, 2019, after a longish bout with stage four cancer in his sixties, like his rival polemicist and Iraq War champion, Christopher Hitchens. As Hitch said, ‘there is no stage five.’ There was hope when I saw Raimondo that a new miracle drug, KEYTRUDA, would give him a hustler’s chance. It didn’t. Justin didn’t believe in miracles, anyways.

Raimondo once called Spectator USA the most essential publication in America, so if you’ve come for a testimonial fully scrubbed of bias, perhaps go elsewhere. I thought for a long time how to handle my 2018 interview with Mr Raimondo, research I undertook for a book I’m planning on the Trump Right and the new foreign policy. Raimondo may have been deliriously concerned for the future of his country, but he lived to see a political revolution that he supported. The ascension of Donald J. Trump, an acerbic critic of a whole generation’s foreign policy, vindicated Raimondo’s worldview: the wars are cracked, and that the only way out is in.

Like a lot of people who encountered him, I am still grappling with what to make of Justin Raimondo. He was a conservative, of sorts, committed at his death to the new Republican party as a vehicle of national salvation. When I asked him if he considered himself an intellectual, not merely a brawler, he answered hesitantly: ‘I would say yes.’

As a tween reader of Antiwar and kindred publication The American Conservative, anti-Bush staples, I found meeting Raimondo reminded me of that scene in Almost Famous, when the green reporter protagonist, William Miller encounters underground rock journalist Lester Bangs. Bangs tells Miller: ‘It’s just a damned shame you missed out on rock ‘n’ roll. It’s over.’

Proto-Trumps are dropping like flies. Raimondo’s demise was followed this week by the death of Ross Perot, the anti-Bush populist, whom acolytes Tucker Carlson and Laura Ingraham, remarkably for any viewer with long-term memory, paid moving tribute to on primetime Fox News Tuesday night. Justin Raimondo may be dead, but the sentiment that the country is to the dogs and the wars are very much to blame is alive as it’s ever been.

Raimondo’s death comes at an inflection point for Trumpism. On the one hand, if Trump leaves office today, he will be the first American president of my lifetime to not push the union into a new war. On the other hand, Trump’s been maddeningly sluggish on the promise of the 2016 campaign: we’re still in Syria, we’re still in Afghanistan, and we’ve riskily turned up the heat on Iran. Tehran’s already 120 degrees in the summer.

Consider Raimondo as a dying optimist – at least on Donald Trump – however. He was also, oddly for a libertine, a culture warrior.

‘The thing is,’ Raimondo told me, ‘why do you think Trump is going around? Have you ever seen a president give so many rallies? I have never seen that in my whole life. The masses. It’s rough. It doesn’t come out neatly. And it’s a struggle for power. And either they win. Or we win.’

After years of opposing the sitting president – backing Pat Buchanan’s challenge to Bush in 1992, heckling Clinton for the rest of the decade, excoriating Bush’s son in the 2000s, and later falling for, but then dumping Obama – Raimondo, at last, was comfortable with the incumbent.

His longtime consigliere, Eric Garris, as well as many colleagues at Antiwar quietly rolled their eyes at Raimondo’s last idee fixe. Broadly speaking, the Antiwar crowd, which along with Yoshi survive Raimondo, is both more ideological and more practical than Raimondo was. They’re clearly not opposed to Trump, but they view his administration, so far, as less of a watershed.

Raimondo heckled me mercilessly in 2018 for my reportage that insisted that John Bolton, an antichrist in foreign policy restraint circles, had the inside lane to be the next national security adviser. I turned out to be right, but that did not diminish Raimondo’s regard for Trump. But he soured somewhat on Antiwar and the anti-war crowd.

‘They want to feel good about themselves,’ said Raimondo of foreign policy realist critics of the administration, such as Daniel Larison of TAC, to which Raimondo grew increasingly hostile toward the end. ‘The whole point is to win.’

Raimondo, unlike many new Trumpists, never renounced his boyhood libertarianism. Neither did Eric Garris, who first met Raimondo in the Seventies in the volcanic San Francisco political scene. I met Garris at Ocean Beach’s Cliffhouse to chat about Justin. He tells me that Raimondo’s life really began in earnest when he left the east coast on a one-way ticket to San Francisco in his late teens. What followed was nearly five decades of agitation.

Raimondo broke early, for instance, with the libertarian powerhouse Koch brothers — a dispute too Byzantine to relay here. Raimondo insisted to me that he was still libertarian, and still fundamentally a follower of the eccentric Murray Rothbard. It’s unclear how support for a White House that’s backed a national industrial policy jives with Rothbardian market fundamentalism, but Raimondo insisted it did.

Garris, on the other hand, seem to know libertarianism is over: for instance, we’re likely to get universal healthcare in this country, he told me, and there’s perhaps little sense in fighting it. Immigration hawks have taken a similar view in recent months, it seems: foreign policy is now the fight that can be won.

Raimondo was the anti-war movement’s visionary. You got the sense that Justin Raimondo believed the Whiskey Rebellion was America’s last just conflict. If he was externally noncombative, he was internally rebellious. Garris asked me not to share the details of some of Raimondo’s more iconoclastic hijinks in the Seventies and Eighties.

Fundamentally, however, the United States in 2019 has a president of the United States who routinely castigates ‘endless war,’ a development that would have sounded like a pipe dream even five years ago. The hawkish Bill O’Reilly’s seat at Fox is now the dovish Tucker Carlson’s. War with Iran is concerningly possible, but it’s an extremist effort, not the groupthink of an uncritical establishment, as Iraq was. That’s progress.

I think it’s now Raimondo’s world, and he’s not living in it.