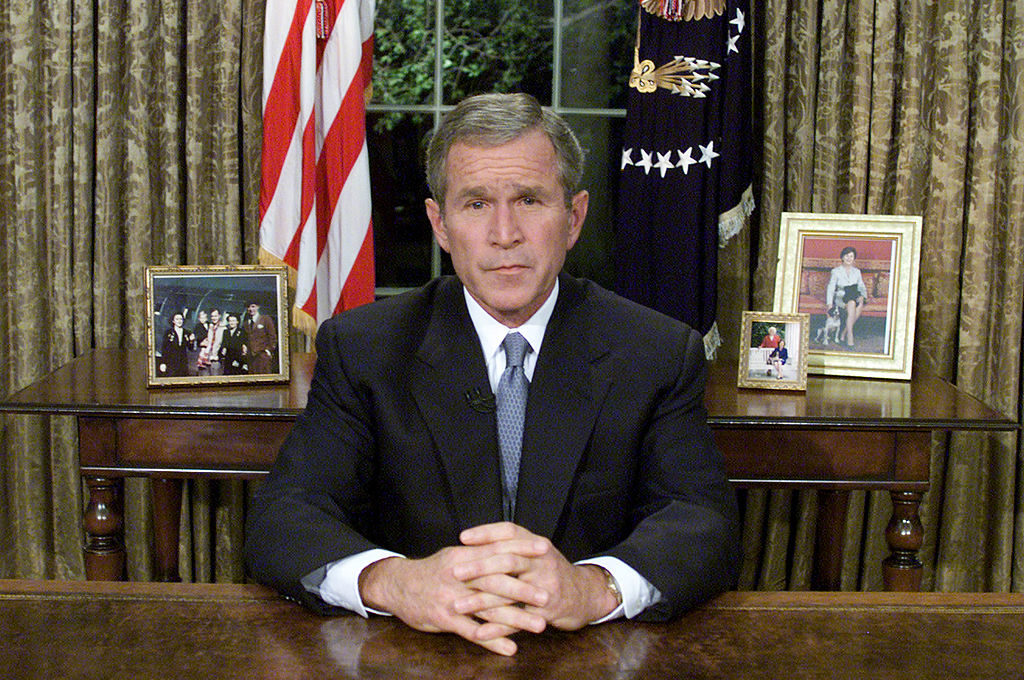

I’ve been thinking about where I was on the eve of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, and my memories of the event are quite depressing. What have we learned?

As a research fellow at the Cato Institute at that time, I was working with other analysts preparing research, authoring commentaries, publishing op-ed articles and giving interviews to the broadcast media, warning about the consequences of the coming American military conquest in the Middle East.

It’s not polite to toot one’s own horn, but we were right. A quick search of Cato’s archives demonstrates how, without any access to intelligence reports, satellite photos, or, of course, the mind of Saddam Hussein, we questioned whether Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction and sounded the alarm about what would happen if the US invaded Iraq, ousted its leader, and tried to establish a liberal democracy there. We had been warning for years that American policy in the Middle East would draw the US into a quagmire in the region.

In the invasion’s aftermath, we challenged what had become a bipartisan axiom: that Washington would advance US interests and values by launching campaigns of “regime change,” “nation building” and democracy promotion in the greater Middle East and elsewhere. We insisted that Pakistan was not a US ally in the fight against terrorism, that Americans would not be able to remake Afghanistan into a stable and functioning democracy, that we needed to leave the place ASAP after destroying al-Qaeda and then also get out of Iraq.

Republicans expressed support for Cato’s plans for privatization and deregulating the economy, and Democrats applauded our ideas on advancing civil rights. But in Washington, the voice of Cato and others opposed to the war in Iraq received scant attention in Congress or from the media. Our positions on the war were eventually mainstreamed — but twenty years too late. When almost everyone in Washington finally abandoned the interventionist strategy in Iraq — and agreed not to repeat it in Iran — it was because it hadn’t worked, having made the Middle East more unstable and strengthened the power of Iran.

I had hoped the lessons of how misguided conventional “wisdom” had led US policymakers into a disastrous foreign policy would be heeded, that policymakers would now consider more contrarian views aimed at avoiding costly overseas entanglements.

Yet here we are again. The foreign policy consensus in Washington is evolving in an interventionist direction, with Republicans and Democrats, liberal internationalists and neoconservatives alike, developing a new dogma that obligates the US to divert its military power and economic resources to contain and even fight two global powers, Russia and China, that supposedly threaten US national interests and values. Even daring to question this new dictum — which unified pundits repeat nonstop, like parrots on crack — will have you branded by the masses as betraying the very legacy of the Founding Fathers.

Just as the 9/11 attacks resulted in more than twenty years of wasteful regime changes and so-called “nation building,” the Russian occupation of Ukraine will prompt a major push for another series of similar interventions to be hailed as another step closer toward America’s global dominance.

What such a move will amount to, though, will be a bonanza for the national security establishment and the military-industrial complex. It will also bolster the influence of liberal internationalists and neoconservatives, while marginalizing that of non-interventionists.

How did we arrive to the same spot we were in on the eve of the Iraq War, when those calling for a more restrained strategy in response to al-Qaeda and international terrorism were shoved to the margins of the foreign policy debate?

Anti-interventionists will always be dealt a bad hand in the war of ideas for several reasons. When it comes to issues of war and peace, Westerners, when faced with a threat to their existence and sense of identity, expect their leaders to “do something” instead of engaging in analysis. Leaders feel the pressure and are eager to exploit the situation with a call for action.

It doesn’t help, either, that policymakers rarely even take the time to read policy papers issued by anti-interventionist think tanks before making their choices. Yes, more people die each year falling in their bathtubs than in terrorist acts, but when images of innocent civilians suffering and being killed in Ukraine produce a powerful public backlash, interventionist politicians gain the upper hand.

What’s more, while most Americans have a basic grasp of issues that affect them directly, like education, healthcare and taxes, they do not have the time to assess complex problems like nuclear strategy, or to follow events happening in places they’ve never heard of. Thus it’s easy for policymakers to simplify foreign policy issues to a good-guys-versus-bad-guys storyline.

The imperial presidency also remains a dominant force controlling resources, information and manpower, which explains why even Congress, let alone a mid-size think tank, finds it difficult to contest the arguments made by the president and members of his bureaucracy.

Advocates of US intervention in response to international crises will always win the debate in the short-run. Only when the balance of power is reversed, and America seems to be losing, will public attitudes change. Or to put it another way: warnings of a quagmire become relevant only when the US finds itself in a quagmire.

This does not mean that challenging the interventionist consensus in Washington is a waste of time; it is certainly better than doing nothing. As one might say to a person complaining he has not lost weight after going to the gym for a long time: “Imagine how much you would weigh if you did not exercise at all.”