One of the first rules of politics and policy is to keep expectations low, lest you disappoint your constituents and embarrass yourself for being hopelessly naive. Apparently President Joe Biden didn’t get the memo.

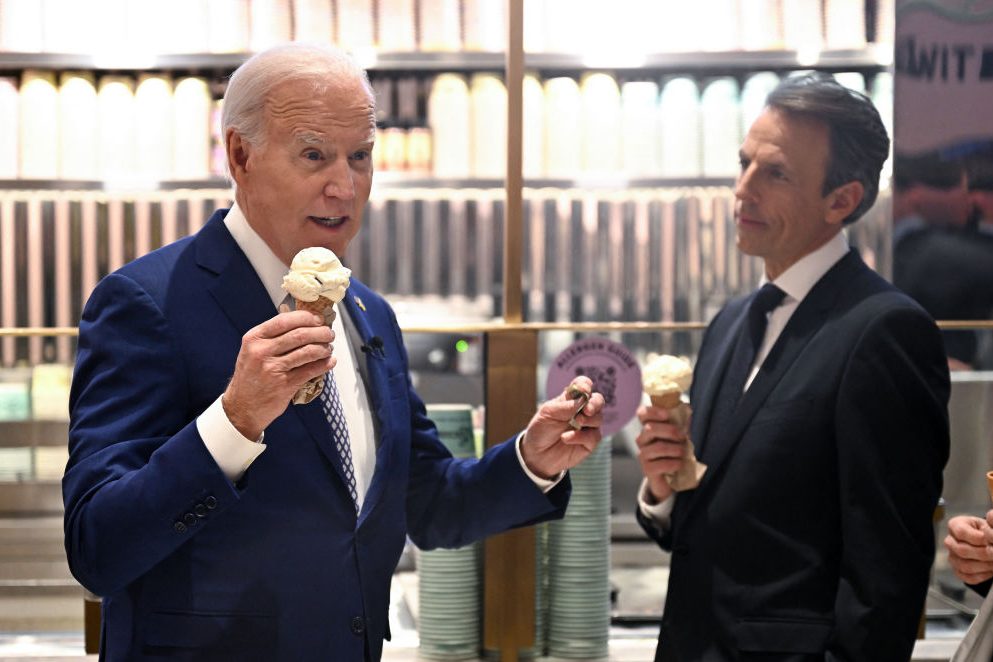

During a stop in New York City this week for a taping of NBC’s Late Night with Seth Meyers, Biden was eager, if not downright giddy, about the prospects of a temporary ceasefire in Gaza. Ice cream cone in hand, the president told the White House press corps that Jake Sullivan, his national security advisor, believes a truce is close at hand.

“My hope is that, by next Monday, we’ll have a ceasefire,” Biden said. Hours later, he followed up those comments with an even more hopeful assessment, telling Meyers and his studio audience that Israel agreed to cease operations during Ramadan, which begins on March 10.

All of this was news to Israel and Hamas, the two parties who have been haggling over terms about a possible truce and hostage release deal ever since the first week-long cessation of hostilities broke down about three months ago. Basem Naim, the chief of Hamas’s political division in Gaza, told the Guardian the next day that the group is still waiting for Israel’s latest draft proposal. An Israeli official was even more grim about the possibility of a deal emerging on Biden’s timetable. “If the conditions that Israel requested were accepted, the deal would have happened today,” the official commented to the Washington Post. “But right now there is no deal, and the deadline is not Monday or Tuesday. I don’t believe we’re as close to a deal.”

None of this is exactly eye-opening. If negotiations between Israel and Hamas were easy, an agreement would have been made weeks ago. Biden’s optimism can’t paper over the fact that the two sides are still working to bridge some pretty wide differences in their respective positions. The general framework isn’t in dispute: weeks of calm to accelerate freeing of the remaining Israeli (and foreign) hostages, the release of Palestinian prisoners and a significant boost of humanitarian aid into Gaza. It’s a similar outline to the week-long truce established by Qatari and Egyptian mediators back in late November, which traded about 100 hostages for 240 Palestinian prisoners — only at a grander scale.

The details and technicalities, however, are mind-numbingly difficult. Those details include the duration of any ceasefire, the ratio of Palestinian prisoners for Israeli hostages, which Israeli hostages Hamas will release first and whether any high-profile Palestinians sentenced for killing Israelis (and if so, whom and how many) will be gifted a second chance. Some reports suggest the length of the ceasefire could be as long as six weeks, while others say forty days. The Israelis are hoping female soldiers will be part of the any hostage-for-prisoner exchange, whereas Hamas will try to hold onto them either for future bargaining or as an insurance policy in the event Israel violates the truce.

Then there is the end-game. Assuming Israeli and Hamas negotiators strike an accord, where would a truce lead? While Hamas is nowhere near being destroyed as a military entity (Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s rhetoric notwithstanding), the group is under intense pressure after nearly five months of incessant Israeli military operations and is thus insisting on a complete end to the war and a full Israeli troop withdrawal from Gaza. Netanyahu, though, has shot down both demands as “delusional” and even ordered his negotiators back home earlier this month to pressure the terrorist group into moderating its terms.

Having tied his entire political persona to the war and repeatedly promising total victory to the Israeli public since the war began on October 7, it’s hard to foresee any circumstances short of Hamas’s leadership handing themselves over to the Israeli authorities in which Netanyahu would cut the war short — particularly when doing so would result in Hamas extending its seventeen-year-long writ over Gaza. And given the make-up of his governing coalition, Netanyahu wouldn’t be able to sign an end-of-war ceasefire even if he wanted to. Two of his most hard-right coalition partners, national security minister Itamar Ben-Gvir and finance minister Bezalel Smotrich (among others) are highly opposed to any concessions to a group that murdered 1,200 Israelis and could very well express their displeasure by bolting the government and throwing Netanyahu out of power, where a corruption trial awaits him.

Ultimately, whether the ongoing truce talks succeed or fail will depend on this fundamental point: would a deal be a short-term respite for the combatants (and the civilians forced to live in a war zone) to breath a bit before for the next round? Or will it be the beginning of a long-term ceasefire? Biden may be giving unconditional military and political support to Israel, but it’s likely he wouldn’t shed a tear if the war stopped. Gaza is proving to be one of the rare issues damaging Biden’s relations with key segments of the Democratic Party’s base, including people of color, progressives, young voters and Arab Americans in pivotal swing states like Michigan, whose Democratic primary is today.

Nobody can fault Biden for expressing his preferences. He clearly wants a ceasefire of some kind, both to stop the bleeding inside Gaza and to start the journey of repairing ties with core constituencies back home. But in raising the bar, Biden risks seeing his hopes crushed by the idiosyncrasies, complications and realities of the Middle East’s longest conflict and looking almost inexperienced in the process.

Leave a Reply