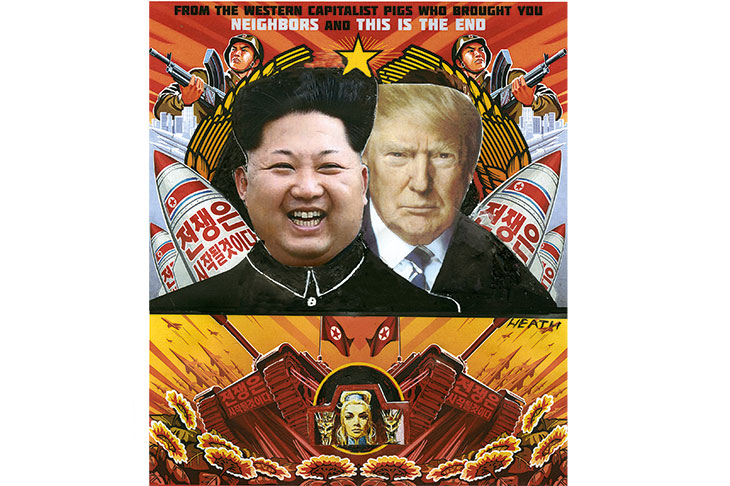

On a humid summer’s day in Singapore three years ago today, Donald Trump became the first incumbent US president to meet with his North Korean counterpart. For all of the summit’s theater, Kim Jong-un’s pledge to ‘work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula’ seems unlikely to be realized. Three years on, and the country shows little intention of either abandoning its nuclear ambitions or reforming Pyongyang. Instead, the regime has tightened its control over society, not least ideologically, after the failure of the Supreme Leader’s five-year economic plan.

In 2018, the leadership assured North Koreans that the country had achieved its primary geopolitical aim of becoming a ‘fully-fledged nuclear state’. That April, Kim announced a shift in party focus to a ‘new strategic line’ — focusing exclusively on domestic economic development. Yet just like the international community’s quest for North Korean denuclearization, domestic economic development has failed to materialize.

Of course, the pandemic has had no small part to play in the stagnation. North Korea was one of the first countries to enter lockdown: the closure of the Chinese border last January had an impact that even the most stringent sanctions have been unable to emulate. What’s more, despite recent reports of Chinese trade picking up, the regime has taken a notably pessimistic turn. State media has declared that vaccines may be unable to protect individuals from mutant strains and that the North Koreans must recognize that the pandemic is ‘unlikely to end soon’.

In response, we see a return to the state’s unique ideology of juche, defined roughly as political and economic self-reliance. The quasi-religious doctrine, formed under the country’s founder Kim Il-sung, is a bastardization of Marxist-Leninism, eventually replacing the latter as the country’s guiding ideology: it prioritizes autarky over internationalism and places human agency above historical materialism. In other words, it is the Kim regime leading the Korean people towards the utopia of a unified, Pyongyang-controlled Korean peninsula. But as more information about the outside world has seeped in, individual belief in the ideology has waned. Yet, the regime is now resurrecting the rhetoric of juche to maintain domestic control.

Kim himself has stressed that the country should prepare for an ‘Arduous March’, a term euphemistically used by the regime to refer to the famine of the 1990s. Beyond preparations for hardship, Kim has also sought to toughen his ideological grip over society. The party has launched a clamp-down on ‘anti-socialist behavior’, particularly focused on younger North Koreans. In April, Kim ordered national youth leagues to adopt ‘a correct view of morality’ and improve their ‘words and acts, hairstyles and attire’.

Teenagers have reportedly been sent to reeducation camps for ‘crimes’ such as listening to K-pop music and watching South Korean drama. While unverified, these reports are plausible given the increasingly harsh tone emanating from the party. To dismiss such rhetoric as mere bluster would be naive. Pyongyang has cut off backchannels with Washington while the prospect of greater inter-Korean economic co-operation has dimmed. With the outside world retreating, Kim will need to focus on domestic control.

An ‘anti-reactionary thought law’ criminalizes the import and distribution of South Korean media and books, punishable by re-education or even execution. Despite the growing illicit access to outside information, Kim is keen to ensure that the party remains paramount. Certainly, defectors speak of the importance of outside contact — books, articles, films, television and music — in broadening North Korean minds.

Much akin to authoritarian leaders in eras gone by, Kim Jong-un is seeking to stamp out any possibility of ‘reactionary’ forces from the bottom-up. Of course, it is erroneous to assume that Kim is the state and the state is Kim. Factions within the party and between the party and Korean People’s Army do challenge and influence Kim’s decision-making.

But the need for a nuclear North Korea is agreed on by all in Pyongyang. Beyond direct military deterrence, the nuclear program also serves a domestic purpose — it legitimates the regime. Three years after Trump and Kim’s meeting, the goal of denuclearization has become increasingly elusive. It remains a waiting game as to whether the Biden administration’s policy of ‘diplomacy and stern deterrence’ will lead to a return to the status quo ante. But the handshakes of Singapore are already a distant memory.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.