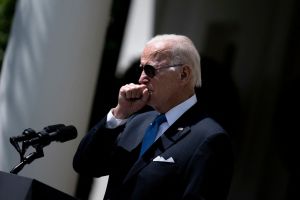

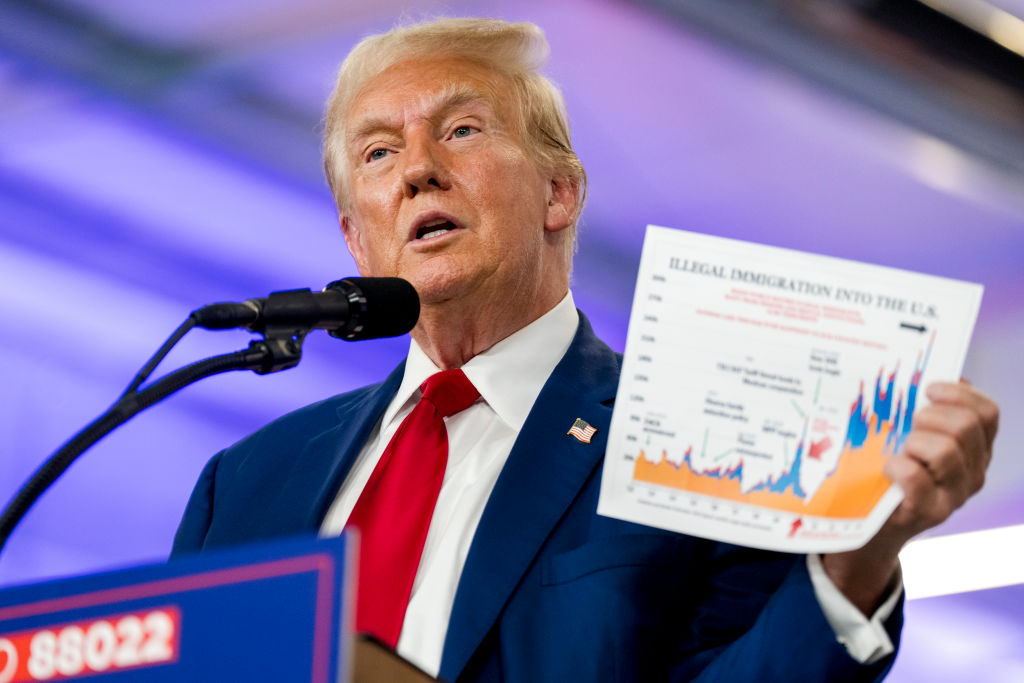

With the end of Title 42, Donald Trump’s helpful bequest to Joe Biden of a means to exclude asylum-seekers on grounds of a health emergency that has long since passed, the administration is bracing for scenes of alien hordes thronging the border. But if there’s one picture the Biden administration least wants to see again, it’s that striking image from September 2021 of a mounted border patrolman appearing to whip a cowering Haitian migrant with his reins.

Then-White House press secretary Jen Psaki reported at the time that Biden found the photo “horrific” and “horrible,” adding “that’s not who the Biden administration is.” That same month, the US deported over 6,000 Haitians, flown with shackled hands and feet to a country many of them had left years before. Overall, Biden has deported three times as many Haitians as the last three administrations combined.

Haiti is notoriously a humanitarian disaster. It thus poses a particular dilemma for an administration spurred by political necessity to appease anti-immigrant sentiment while at the same time exhibiting a modicum of compassionate concern for the benefit of Democratic Party base constituencies. Its preferred solution to the problem was unveiled in January in the form of a “humanitarian parole program,” designed, in the words of Homeland Security secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, to “provide humanitarian relief consistent with our values.” The program, which also applies to Nicaraguans, Cubans and Venezuelans, grants migrants admission to the US and the right to stay and work for two years. Applicants must provide a US-based sponsor and a passport. Anyone attempting entrance any other way is immediately deported and barred from applying for the parole program in the future.

Predictably, demand for a “Visabiden” exploded in Haiti. Most Haitians lack IDs such as driver’s licenses, let alone passports, so relevant offices were quickly swamped by thousands desperate for a passport so they could then apply for the visa.

Such urgency is in no way surprising, given that Haiti is in a state of near-total anarchy. In the Canapé Vert neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, just a seven-minute drive from the main passport office on Avenue John Brown, thirteen members of the Kraze Barye (Breaking Barriers) gang, on their way to reinforce comrades pinned down in a gun battle, were recently stopped at a (rare) police roadblock and beaten to death or burned alive by angry residents. On a recent Sunday in a big Port-au-Prince church, Eglise de Jesus-Christ Full Gospel, the pastor led his flock in a call and response: “Bless my machete, so that when I use it against a bandit, it cuts flesh, that it cuts bone, that it makes them shit their pants,” he intoned, with the congregation echoing each line.

Such sentiments have excited eager speculation among progressives in the US that Haiti is somehow on the verge of a “new revolution,” in which people power will drive out the gangsters and corrupt government. Informed opinion on the ground disagrees. “There’s the narrative of a community defending itself, fighting horrible gangs. But this is not a good thing, it’s a sign of the complete breakdown of society,” Jean Marc de Matteis told me. He is CEO of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital which miraculously continues to function as the sole health provider for 700,000 people in the Artibonite valley inland from Port-au-Prince. “There’s a complete absence of the state. In a country of twelve million people, there are just 12,000 police, on paper, but only about a third of them are on duty at any one time.”

There have been no police guarding the road between his hospital and the capital since the last police station was sacked and its seven officers were executed a month ago. Recently, a truck carrying $100,000 worth of desperately needed medical supplies on its way from the port was hijacked by a neighborhood group to use as an anti-gang barricade. It took De Matteis days to negotiate its release. Ninety percent of Haiti’s food, he reminded me, is imported (largely thanks to Bill Clinton, who ruined Haiti’s farmers by forcing the government to drop tariffs on imported rice). “But there’s no fuel to bring the food up from the docks, so over 500 people a day are dying of hunger.” A further 20,000 are on the verge of starvation, and fully half the population, 6 million people, are going hungry. The country depends almost entirely on generators to supply electricity. But with no fuel to power the generators, “banks cannot open, schools cannot open, hospitals cannot function.” (His own providentially runs on solar.) Day and night, Port-au-Prince echoes to the sound of automatic gunfire, and the chaos is reaching deep into the countryside.

Given this apocalyptic situation, it comes as no surprise that Haitians who can take advantage of Biden’s parole scheme will do so, which means, in effect, those educated Haitians with connections in the US to sponsor them and the skills and necessary internet access to navigate the bureaucracy. As a result, Haiti is losing the people essential for any prospective reconstruction of the state. A third of the remaining police have already applied. The doctors and nurses are leaving — some hospitals have lost 40 percent of their skilled staff. Marc Julmisse, executive director of Partners in Health, which operates fifteen hospitals and clinics around the country, told me “we’re losing midwives, which Haiti already lacks. We’re even losing drivers and security guards. They don’t want to go, but they have no other option.”

While the state disintegrates at an accelerating pace, there has been no shortage of appeals for international intervention, appeals that have largely fallen on deaf ears. “Haiti has asked the UN and the OAS in October of last year for help to stem the massive level of violence afflicting the country,” lamented Christobal Dupouy, special representative in Haiti of the secretary-general of the OAS. “After months of discussions, the needle has not budged, and Haiti continues a downward spiral.” Roberto Alvarez, foreign minister of the neighboring Dominican Republic, listed for me the various excuses forestalling international action, including the rules governing UN peacekeeping operations that preclude use of force and require prior agreement of all parties — difficult to obtain from the 200 gangs that currently control 90 percent of Port-au-Prince.

It is fair to say that such interventions have an unsavory reputation in Haiti. Most recently, a UN peacekeeping operation between 2004 and 2017 imported cholera which killed thousands and left a legacy of rapes and abandoned children. Nevertheless, a February poll commissioned by Reuters revealed that 70 percent of Haitians favor some kind of international force. De Matteis feels confident that such action is ultimately inevitable. “People say, there’s no appetite for it. Right now, yes. But next week, next month, when there’s a fully laden wooden sailboat with 300 pregnant women on it, that capsizes in front of TV cameras, or more and more images people being hacked and burned alive, there will be no choice but to intervene.”

However, it may be that the Biden administration is not that worried about unpleasant images of capsizing sailboats or large numbers of seaborne fugitives turning up on Florida beaches. The US Coast Guard, after all, patrols off the island to prevent any such egress.