Do you have a favorite Habsburg? Mine is Maximilian I, the first and last ruler of the Second Mexican Empire. Americans may be vaguely aware of him because a defeat of his French allies is commemorated annually on Cinco de Mayo. His struggles echo the experience of many unlucky rulers supported by fickle foreign patrons: Abandoned by the French and besieged by belligerent locals, the ill-fated emperor stubbornly refused to abandon a throne he hadn’t much wanted in the first place. His last words to the firing squad were, “Aim well, muchachos.”

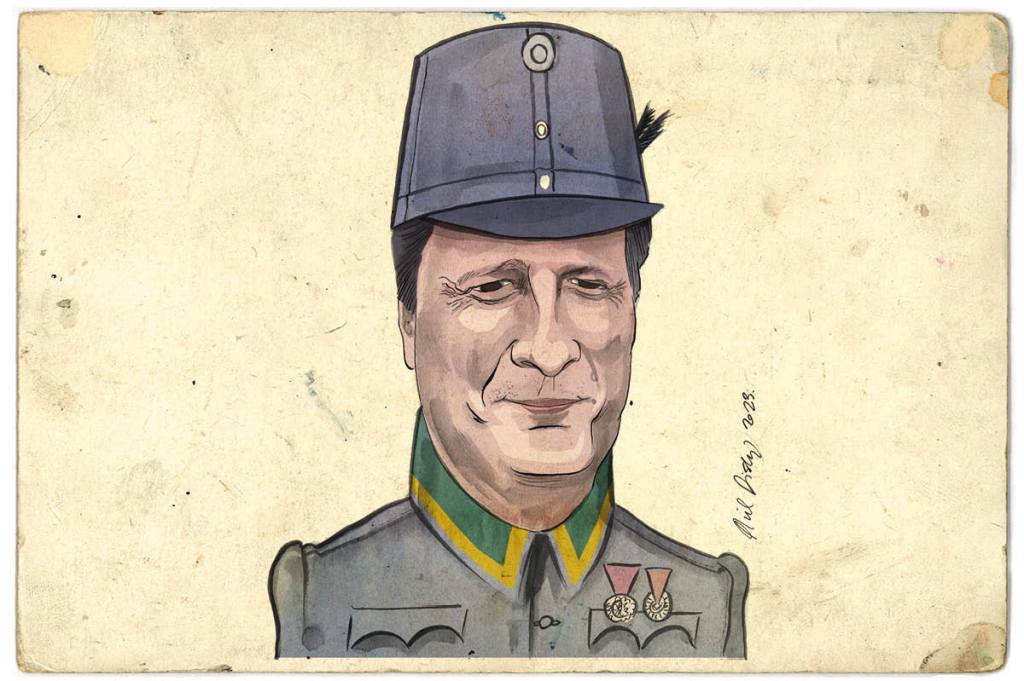

Poor Maximilian doesn’t appear in The Habsburg Way: Seven Rules for Turbulent Times, a short introduction to the family by Eduard Habsburg, Hungarian ambassador to the Holy See and great-great-great-grandson of Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary. This is not a reflection on Maximilian’s character. A book cataloging all the interesting or notable figures from a dynasty that dates back to the tenth century would require several volumes.

Luckily for casual readers, this is not an academic tome. Written in the breezy style of a travel guide or self-help manual, The Habsburg Way combines a readable introduction to the family with some surprisingly pointed ideas for navigating modern life from a Catholic perspective. The book’s tone mostly recalls tourist brochures from one of the charming European cities once ruled by Eduard Habsburg’s ancestors. There are plenty of interesting facts and quirky details, but you needn’t worry about cramming for a test.

Serious Habsburgophiles should look elsewhere for a comprehensive history, but readers in search of something more accessible will appreciate the ambassador’s light touch. They may also be surprised by the breadth of his family’s influence. From Spain to Holland to Mexico, to Trieste to Bucharest, the House of Habsburg and its offshoots collected an impressive array of lands and titles — the dynasty ruled the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire until its collapse at the end of World War One.

Ambassador Habsburg embodies many of his family’s characteristic traits. He has six children, fitting for a famously fecund dynasty that acquired much of its land through marriage and inheritance rather than conquest. Like his distinguished ancestors, the ambassador is quite cosmopolitan — he grew up in Germany, Austria and Venice, speaks perfect English, and had to take a crash course in Hungarian before assuming his current post (his Hungarian, he admits, is still only “so-so”). And, of course, he is very, very Catholic.

This may confound some people’s priors about committed Catholics: Habsburg is famously active on Twitter, posts YouTube tutorials on how to cook goulash and occasionally resorts to classic Americanisms like “weak sauce.” He prefers Dune to Star Wars, in part because the former’s ideas about imperial rule are much closer to the Habsburg model.

But he’s just as likely to share video of a beautiful liturgy or photographs of the baroque Counter Reformation churches that mark former Habsburg territories from Prague to Tyrol, or suggest to his Twitter trolls that they expand their frames of reference beyond Gavrilo Princip clichés to take in “something else for a change,” say, the defenestration of Prague.

Despite Habsburg’s obvious sense of humor, though, his book’s marriage of popular history and Catholic-inflected conservatism can be a bit awkward, especially when Habsburg himself falls prey to using overdone right-wing tropes. He decries “hook-up culture” and makes a case for, if not arranged marriage, marriage embedded in the Catholic faith. An Austrian archduke who faced down Napoleon is praised for not “lead[ing] from behind,” a stale reference to a widely mocked Obamaism from 2011. The United States, we are told, “was built on the principle of subsidiarity,” a term for political decentralization presently in vogue in some American Catholic circles. There are some interesting parallels between American federalism and Catholic political theory, but this would be news to the motley collection of deists, Enlightenment rationalists and Protestants who made up most of America’s founding generation.

Perhaps you’re wondering why anyone should care about a family whose leading lights are no longer archdukes or emperors but mere civil servants. The Habsburgs have more than a whiff of anachronism about them. Aren’t we well rid of royal dynasties and their old-fashioned issues?

Alas, the problems that bedeviled this ancient house are not unique to time, place, or protagonist. While the Habsburgs ruled, reformers, rebels and revolutionaries could blame the woes of east and middle Europe on a convenient imperial target. The dynasty is long gone, but the problems remain.

Indeed, the best compliments paid to the Habsburgs are the varieties of fraught national, economic and ideological programs the region has experimented with since the fall of Austria-Hungary. The dynasty’s record has been burnished by the struggles of the successor regimes, from Horthy’s to Ceaușescu’s and beyond, which have grappled with the same challenges that once confounded Ambassador Habsburg’s great-great-great-grandfather, usually with less success and often with more brutality.

Modern political science has also risen to defend Habsburg honor. In its heyday, the Austro-Hungarian Empire deployed a legion of officious bureaucrats to survey territory, collect taxes and manage its diverse and often unruly citizenry. This creaking edifice was widely mocked, but a 2011 study found that former Habsburg territories still enjoy less corruption and higher trust in public officials than their neighbors. Even in death, the dynasty continues to serve its subject peoples.

The foreword to The Habsburg Way is written by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán, Ambassador Habsburg’s controversial boss. By rights, Orbán should despise the Habsburgs, a dynasty that spent considerable time and energy suppressing Hungarian nationalism. Yet, in an interesting twist, even Orbán has learned to appreciate his imperial predecessors. “We shaped each other, and sometimes it hurt,” writes the usually combative prime minister, in a wistful tone that suggests a bygone but fondly-remembered love affair.

Orbán is not alone. Almost as soon as the dynasty disappeared, there was a sense among its former subjects that something ineffable had been lost. Habsburg nostalgia inspired a cottage industry of post-Imperial literature, from Gregor von Rezzori’s The Snows of Yesteryear to Joseph Roth’s The Radetzky March to Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday. Around the turn of the last cen- tury Zweig wrote, “It seemed merely a matter of decades before the last vestiges of evil and violence would finally be conquered.” He would kill himself in 1942, despairing for Europe’s future.

Ambassador Habsburg laughingly avers that he never reads these “dusty books,” preferring sci-fi epics (this is the sort of thing you can get away with saying if your family’s lineage reaches back over a thousand years), but the peculiar, nostalgia-drenched subgenre of novels and memoirs from the twilight of the dynasty is a testament to the Habsburgs’ hold on Europe’s cultural imagination. Even Dune, a galaxy-spanning epic about a crumbling empire beset by squabbling nobles and rebellious subjects, owes something to them.

The Habsburg Way is dedicated to Charles I, or Blessed Emperor Karl as he is known to Catholics, the last ruler of Austria-Hungary. Charles had the misfortune to inherit his throne amid the carnage of World War One. Having fought on the front lines, he sought to make peace with the Allies, but by this point Austria-Hungary was too dependent on Germany to conduct an independent foreign policy. After the war ended, Charles was forced to give up his crown. He made two attempts to recover the Kingdom of Hungary before dying in exile of pneumonia.

By conventional standards, the younger Habsburg notes, Charles I is one of history’s losers: he couldn’t win the war, broker a favorable peace deal or even save his tottering dynasty. The last emperor’s postwar attempts to reconcile his multiethnic realm with Woodrow Wilson’s insistent (and disastrous) program of national self-determination have the air of a desperate suitor pursuing an indifferent lover. Charles’s later efforts to become king of a much-reduced and defeated Hungary are almost pathetic. Why bother with such a thankless task when you can enjoy a life of comfortable exile in a Swiss chateau?

Faithful to the end, Charles I’s noble but doomed labors recall his cousin Maximilian, who had to be cajoled into accepting a Mexican throne that would eventually cost him his life. Maximilian was supposed to be a reactionary figurehead, propped up by conservative landowners and the French army, but he proceeded to alienate his political allies by backing modest land reforms. When Maximilian left the empire for Mexico, he was in the middle of building a snow-white palace on a seaside promontory outside Trieste. He would not live to see it completed.

“People have a certain melancholic desire for leaders we trust,” says Eduard Habsburg. “Melancholic” and “dutiful” are fitting adjectives for a dynasty that is gone but not forgotten. If you were to sum up the Habsburg way, doing your level best under trying circumstances would be a reasonable epitaph.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.