These days technology rules the roost. In the West at least, the Greeks (as ever) got there first. Like the Romans after them, they were fascinated by hydraulics, springs, pistons, gears, sprockets, pulley-chains — and experimented with them to produce a whole range of lifting, digging, and propelling devices, especially for military purposes.

A breakthrough happened when some Ancient Greeks, observing that the earth and heavens revolved in predictable circles, mimicked them in hand-cranked, bronze mechanisms consisting of complex, linked cogwheels to replicate and predict that movement — the first analog computers.

The single recovered example is the Antikythera machine (second century BC), named after the island off which it was found. It has at least thirty-five wheels, the largest of which has 223 teeth. On similar lines we read about Archimedes’ planetarium (third century BC) simulating movements of the Sun, Moon and planets, and Ptolemy’s astrolabe (first century ad), a sort of GPS system — and much else.

But the research did not end there. Greeks were equally fascinated by forces of nature — wind, gravity, vacuums, pressure — and designed a range of astonishing gadgets to exploit their potential. Among them were a wind-powered organ, a robot pouring glasses of wine, a glass that constantly refilled itself and a burglar alarm.

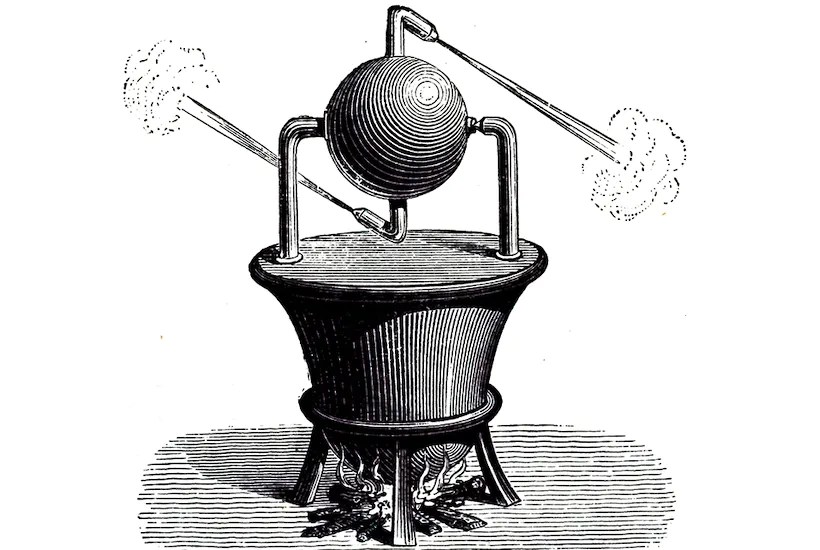

Even more dramatic was jet propulsion. Archytas’ animal bladder, looking likea flying pigeon (fifth century BC), was pressured up with steam from a boiler and then released. Heron’s steam engine (first century AD) might even have generated an industrial revolution. It consisted of a metal sphere, fitted with a curved nozzle on either side, propped up by two pipes which fed steam into it from a boiler. The steam, forced out of the nozzles, caused the sphere to rotate.

In other words, the Greeks’ curiosity extended far beyond the purely cerebral. They wanted to understand the nature of matter not in theoretical but in practical terms. What they would have given to be alive today!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.