How can the next British prime minister survive without a majority and with Brexit to solve? It defies the imagination. Yet if they do survive Brexit, against all odds, there could be an even bigger horror waiting around the corner: global recession.

For three years the economy has defied doom-laden predictions by aggrieved Remainers. Suddenly, though, the economic news is looking ominous. In May, retail sales fell by 2.7 percent compared with a year earlier. The manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), an indicator which runs a month ahead of Office for National Statistics data, plunged from 53.1 in April to 49.4 in May, where any figure below 50 denotes shrinking activity. It was inevitably blamed by many on Brexit, but the gathering downturn is global. In the eurozone, the PMI for manufacturing has been below 50 for four months —and in Germany it is down to 44.3. It isn’t just Germany’s industrial sector: the economy as a whole avoided recession in the last three months of 2018 by the skin of its teeth. Italy was not so lucky, although it did succeed in clambering out of recession — just — in the first quarter of 2019.

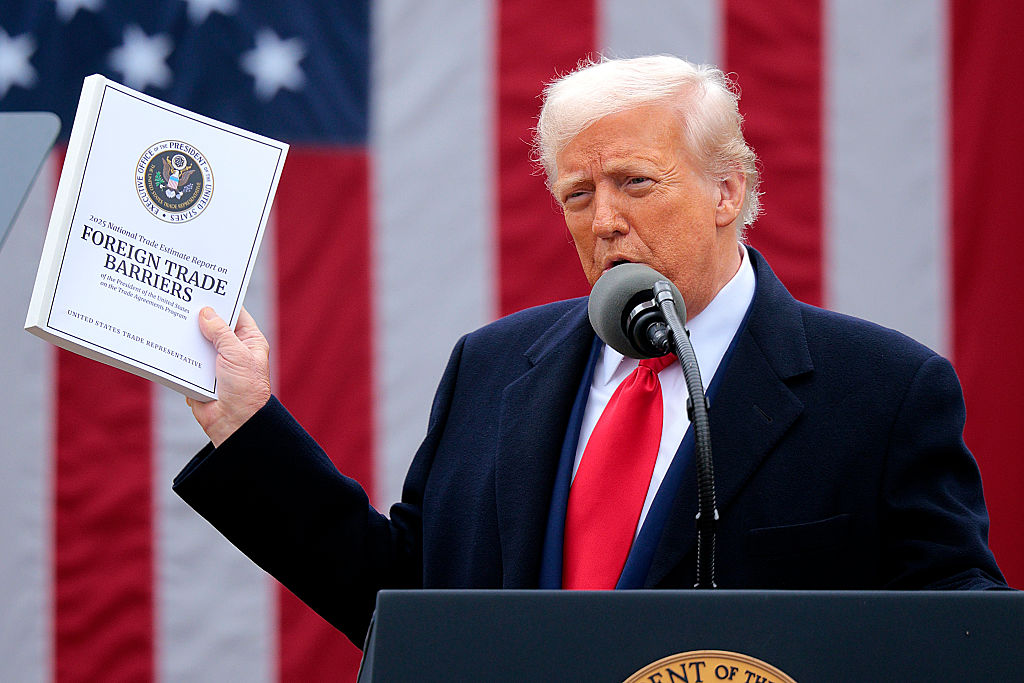

Last month, manufacturing moved into contraction territory in Japan and South Korea, too. Emerging economies have been stuttering. And now comes Trump’s trade war. Trade wars, the president claimed on taking office, are good and easy to win. But perhaps not good and easy enough. The imposition by the US of punitive tariffs on nearly all Chinese goods has unnerved markets, which had so far remained robust. The effect on world trade is beginning to show. In April, the global trade index published by the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis showed its first year-on-year fall since the 2008/09 crisis — although it did rebound last month to annual growth of 0.5 percent. It is a measure on which a British PM needs to keep a very close eye.

There is still no inevitability about a recession, yet they have a habit of creeping up on us every few years with little warning. We have now had what is beginning to look like a remarkably long period without one. But a recession now would be politically devastating. For the moment, the word ‘deficit’ has all-but disappeared from political debate. Last year, the government borrowed £23.5 billion — down from £153 billion in 2009/10. In terms of percentage of GDP, the deficit has fallen from an 9.9 percent to an innocuous-sounding 1.2 percent. Yet after years of economic growth, public spending ought to be in surplus. Gordon Brown showed how devastating the consequences are if you enter a recession with a deficit: within three years the extra demand on the public purse through rising unemployment and reduced tax receipts sent the deficit soaring from £38 billion to £153 billion. As Nigel Lawson discovered, running even a modest surplus is no guarantee of avoiding fiscal disaster — the recession of the early 1990s reversed a surplus equivalent to 1.7 percent of GDP to a deficit of 5.1 percent of GDP in three years.

We have just been through a decade of what the Conservatives’ opponents have damned as ‘austerity’ — a term which Philip Hammond has unwisely adopted himself. How will a future Conservative chancellor make the case for restraint in public spending when his predecessor has sanctioned the idea that balancing the state’s books amounts to a kind of monkish denial? The next chancellor (Hammond surely cannot keep his job after threatening to bring the government down in the event of a no-deal Brexit) could find himself with a ballooning deficit and no political authority to act to contain it.

It has become commonplace over the past fortnight to claim that Theresa May is leaving office with no discernible legacy. It is also unfair. The lowest unemployment rate in 45 years is surely an achievement worth shouting about. Yet for unemployment to carry on falling requires the economy to carry on growing, and that is far from guaranteed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.