There’s a online blacklist of men you should avoid dating and I’m on it. I discovered this over the summer when a colleague gave me a nudge and showed me a screenshot of my dating profile. “That’s you, isn’t it?” A wave of fear passed through me. I had been posted on a Facebook group named “Are we dating the same guy?” I set out to discover more.

The group itself was easy enough to find. It was started in New York last year to help the city’s single women avoid “red flag” men. The group describes itself as a place where women can “warn other women about liars, cheaters, abusers or anyone who exhibits any type of toxic or dangerous behavior.” Now it has more than 2 million members from 120 cities across the world. The London group has nearly 73,000 members.

Joining the group was going to be less easy: for starters, you have to be female. To gain access, members have to go through a rigorous and tightly controlled screening process. Applicants must regurgitate, “in their own words,” the group’s 900-word rules-cum-manifesto. No men, no sharing outside the group. Moderators do reverse-image searches of profile pictures to catch fake accounts. There’s more than a hint of paranoia: you’ll be banned if you “mention this group or the existence of groups like this on social media, on a podcast, on the radio, to the media, or anywhere else public.”

A friend kindly lent me her Facebook account and I passed the application. Inside, there’s a general format to the posts. Someone will post pictures of a guy and ask the crowd if there is any gossip about him. People will respond with intel if they have it. Sometimes it’s an ex-lover, other times a friend-of-a-friend, on rare occasions a heartbroken wife. One anonymous user asked about Joe, twenty-six, from north London. The photo was of him in his bathroom wearing a tank top and sunglasses. “He only seems present while I’m with him,” she said. “When I’m not there it feels like out-of-sight out-of-mind.” There was one response below: “Matched on Hinge with this guy, chatted, had a call, then he ghosted me.” Another girl asked for advice on her boyfriend. He had recently cheated and she didn’t know what to do. “Expose him,” was the advice. “If you have pictures of him with you, expose him. He played you, it is time that you play with him.”

The group addresses the main problem with modern dating: the fact that you don’t know who you’re meeting. Unlike with traditional matchmaking, on a dating app there is no real vetting process. Instead, you learn about your match in a piecemeal fashion. Dating apps make cheating easy, when every swipe is a fresh slate. So at a time when a large proportion of the under-thirties rely on them to initiate romantic relationships, this kind of group makes sense.

In theory it’s akin to a benevolent, city-wide sewing circle. The posts varied from innocuous to catty, concerned to tearful. Voyeuristic, sure, but not inherently harmful. It felt very different when I found myself on the chopping block, though.

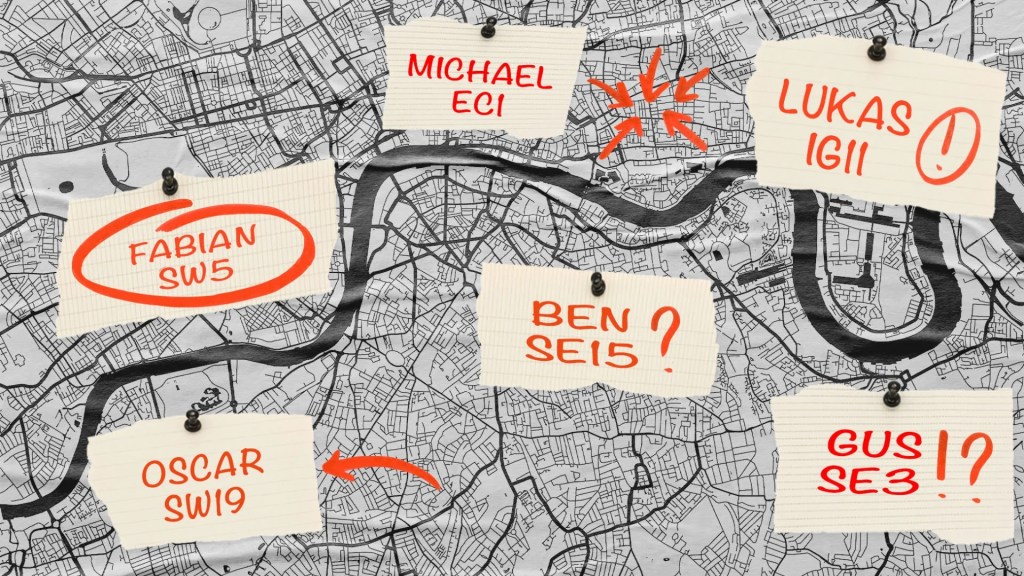

“Fabian, SW5,” it said, accompanied by a screengrab of my dating profile. “He really rushed the relationship along very quickly and asked me to be his girlfriend, invited me to go to Paris etc. Last week when he was meant to be visiting my family, he canceled and wanted to drop the girlfriend-boyfriend label while he ‘figures himself out.’ Found out yesterday that he had taken another girl to Paris on the weekend.”

She was right — she exposed my lies. I told her I was committed while I pursued a relationship with a French girl. It was bad behavior, I know. But love is complicated.

I was unlucky but lucky. Unlucky because I’ll have an association with the group indefinitely — any woman can join it, search my name and read the post. The crawling feeling you get when a very personal part of your life is available for the world to see will take a while to fade. Lucky, however, because she posted the truth. There is no verification of the stories on there, no fair hearing. Any woman with a vendetta has the potential to do a large amount of reputational and emotional damage. One Reddit user who found himself on the group said: “It’s weighing on me and leaving me depressed. It seems that every date carries the penalty of an ignominious and dishonest public shaming.” Had my ex decided to stick the knife in with a few untruths, it could have been a lot worse.

It was an embarrassing experience, but I learnt from it. Before, I dated in a way that could have been designed by Jez from Peep Show. (“Sometimes I tell them I love them early on on a first date just to get things off to a good start!”) Now, I’m more open and honest. The French girl and I are in a happy, stable relationship — we’re even getting a cat.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine.

Leave a Reply