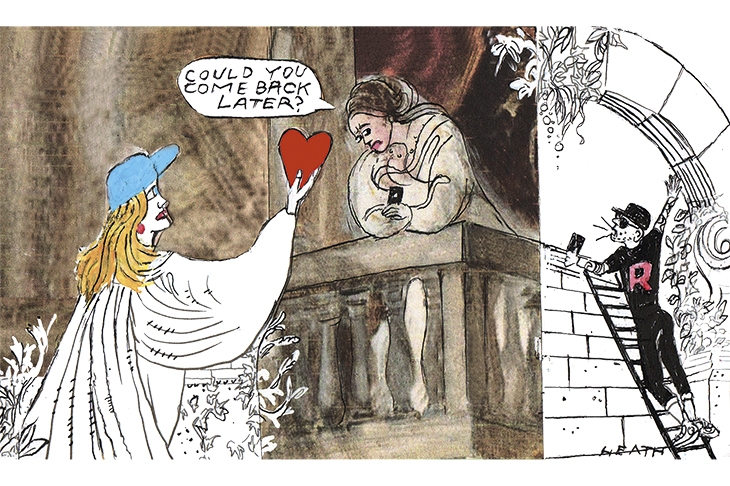

Have you made your “date-me doc” yet?

“Date-me docs” are, per an article in the New York Times last week, “long, résumé-like dating bios” — think of them as the antidote to terse, image-reliant dating apps.

They’re thus far confined to the digital outposts of startup, Rationalist and Post-Rationalist communities; at this point it would be more accurate to describe them as a specific cultural phenomenon than a reaction to dating apps. Whereas dating apps such as Hinge and Tinder are made for “normies,” websites such as OkCupid — where the term “sapiosexual” was originally popularized — or even Craigslist tended to attract a more eccentric caliber of dater. More than anything else, the “date-me-doc” is the cry of a certain type of (usually) San Francisco-based techie, yearning to return to an era where online dating was for and by people like them.

The personality types that these subcultures attract are better suited to wordier, more cerebral dating profiles, e.g., the ones for which OkCupid was once so notorious. These communities also tend to have very specific social norms, which may seem “dorky” or “unreasonable” to outsiders, making dating apps untenable. Looking at these profiles, it’s not just their length that stands out — they’re also jargon-heavy. They’re not intended for everyone; instead they’re full of signals to other people within the subculture. Even the act of creating one at all says something about the person.

The rise of matchmaking apps like Swan, Cuffed and Keeper, along with “wife bounties” — which also started growing in popularity within these same communities during the Covid-19 pandemic — came about for the same reason. Their users didn’t only want to get married; they wanted to marry “within network.” If your community tends to be biased against marriage or marriage within a certain age range, then matchmaking and incentives like thousands of dollars in exchange for an introduction to your future spouse suddenly make a lot of sense. (This also reflects the demographics of the people doing these things — is it a wife bounty or finder’s fee?)

In a wider sense dating app fatigue is real and not particularly new. However, the problems between the sexes run much deeper than just being “sick of the apps.” There’s a growing sense that things are irrevocably broken: depending on who you ask, we’re experiencing a masculinity crisis, a femininity crisis, a demographic crisis, et al.

Much has been written about the most reactionary expressions of this, like the appropriately-named “reactionary feminism,” influencers like Andrew Tate and of course, the incel. We see the content that encourages young women to see sex as a transaction in myriad forms. Yet the way these topics are discussed makes it seem like the dissatisfaction expressed by these groups — and their popularity — is a tool of radicalization or a sinister trend. But young people aren’t being poisoned against one another by cynical influencers. Influencers are exploiting and amplifying a group already in despair.

One young man I spoke to, who is definitionally an “incel” but does not identify with the subculture, says that he feels like the sexes are two very segregated cultures. He described the growing gap between the sexes to me as if it were a prison. Other men online say modern women are a waste of time, with some smaller communities saying that the wholesome woman they deserve, as a matter of self-respect, doesn’t exist outside of anime.

The term “femcel” has also been popularized in the last couple of years. Like “incel,” “femcel” has been broadened to include a number of female personality types, but its emergence is indicative of a brewing discontent. Whether it’s voluntary or involuntary, women are struggling with romance just as much as men. It’s not surprising that it’s gained popularity alongside the increased visibility, and perhaps growth, of radical feminism on platforms such as TikTok and Twitter. It’s understandable that some women — especially young women who’ve spent most of their development online — would see it as a refuge in a sea of anti-woman content.

Unrestricted access to the internet has given women and men the chance to be exposed to the darkest corners of the psyche of the opposite sex. While these clearly don’t accurately represent masculinity or femininity, nor are they necessarily meant to be taken literally, the result has been a souring on online dating. What comes next — whether date-me-docs or having to talk to people in real life — will be interesting to watch.