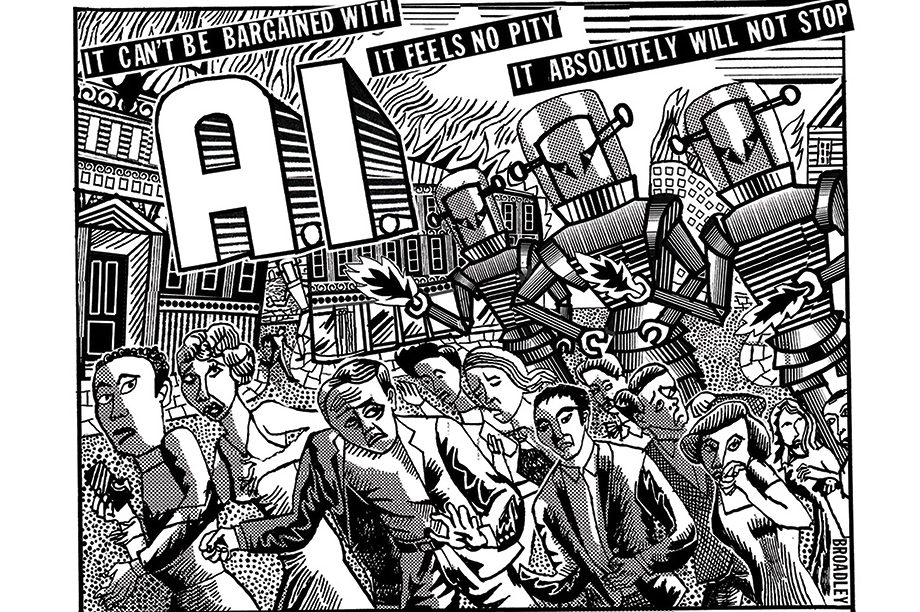

James W. Phillips was a special advisor to the British prime minister for science and technology and the lead author on the Blair-Hague report on artificial intelligence. Eliezer Yudkowsky is head of research at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. On SpectatorTV this week they talked about the existential threat of AI. This is an edited transcript of their discussion.

James W. Phillips: When we talk about things like superintelligence and the dangers from AI, much of it can seem very abstract and doesn’t sound very dangerous: a computer beating a human at Go, for example. When you talk about superintelligence what do you mean, exactly, and how does it differ from today’s AI?

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Superintelligence is when you get to human level and then keep going — smarter, faster, better able to invent new science and new technologies, and able to outwit humans. It isn’t just what we think of as intellectual domains, but also things like predicting people, manipulating people, and social skills. Charisma is processed in the brain, not in the kidneys. Just the same way that humans are better than chimpanzees at practically everything.

JP: Do you think the trajectory from ChatGPT4 to human level intelligence and beyond could be quite fast?

EY: If you look at the gap between GPT3 [released in March 2022] and GPT4 [released a year later], it’s growing up faster than a human child would. Yann LeCun, who heads up research at Meta, said that GPT3 failed when it was asked something along the lines of: “If I put a cup on a table and I push the table forwards, what happens to the cup?” LeCun claimed that even GPT5000 wouldn’t be able to pass this test. Yet GPT4 passed it. So this is an illustration of the degree to which we have no formal scientific basis to say exactly how fast things are going, or even measure exactly how quickly things are moving. In an intuitive sense, things seem to be going quite fast. It’s not that GPT4 is smarter than you, it’s smarter than GPT3.

JP: One of the things that’s shifted in the past few years is the realization that throwing very large amounts of data and computation into machines produces effects in ways that we can’t predict. This is unlike other tech issues. When you see a nuclear reactor, for example, you’ve got the blueprint, you’ve got the designs, you can understand how it behaves. But when it comes to AI, it’s very difficult for policy-makers to understand they are dealing with something unpredictable. Concerns over AI are often dismissed as eccentric, and because we don’t understand the technology, it’s very difficult to explain it. You’ve said before that as soon as you get a highly superintelligent form of intelligence, humanity will be wiped out. For many, that’s a big jump. Why do you believe that?

EY: It’s not that anything smarter than us must, in principle, destroy us. The part I’m worried about is if you make a little mistake with something that’s much smarter than you, everyone dies rather than you get to go back and try again. These systems are more grown than built: we have no idea what goes on inside of them. If they get very, very powerful, they might not want to kill you but they do other things that kill you as a side effect, or they might calculate that they can get more of the galaxy for themselves if they stop humanity.

JP: Can you explain why it would do that? And how, even, could it?

EY: Well, if it’s much, much smarter than you, then it will likely get to the point of self-replicating. Yes, it might require humans to do a lot of computation. This will require fusion power plants in order to power it. If we build enough of these, we would start to be limited by heat dissipation before we run out of hydrogen in the oceans. So even if it doesn’t specifically go out of its way to kill us, we could die when the oceans boil off and Earth’s surface gets too hot to live on because of the amount of power that’s been generated. Now, it could go out of its way to save you if it wanted to do that but it’s not likely to. We don’t know how to make it want to save us.

JP: That’s the critical point: we don’t know how to align the machine with human values. A classic example is Nick Bostrom’s paperclip maximizer: you ask it to produce as many paper clips as possible and pretty soon it has killed everyone and turned the whole world into paperclips.

EY: This is oversimplified for a couple of reasons. One is that you can’t make it want paperclips. Paperclips are something it ends up wanting by accident. Problem number two: what kills you isn’t going to be an AI that was deployed to a factory, it’s going to be a frontier thing in the research lab that probably hasn’t been deployed by anyone at all.

JP: Where would you put your confidence level on the hypothesis that everyone dies?

EY: If we go ahead and build a superintelligence that is anything remotely like the current technology and the current social situation where you have got the heads of major AI labs denying that any problem could possibly exist, and if we just plunge ahead as we are currently, the probability is like 99 percent. If we keep going in a straight line, we all die.

JP: In the early days AI pioneers were much more open that they were trying to build machines that could do anything a human could do, but it seems like that has gone quieter over the past couple of years. When I speak to senior government science advisors, they don’t seem to get what the end goal of places like OpenAI [the company that created ChatGPT] is. I don’t know if that’s deliberate or if that’s just the way the media is reporting it but it seems that end goal hasn’t filtered through to the public.

EY: Back in those days you could say “Yes, sure, we’re going to build something smarter than humans” — ChatGPT didn’t exist yet so people didn’t take that seriously. Then AI came along which could talk to people and people were like: “Wait, you’re doing what?” It was always apparent to me that you’d get to superintelligence eventually if you just kept pushing. I realized this would mean a major planetary emergency coming up in an unknown number of years.

JP: There is a form of superintelligence that could come into existence that would, almost by definition, be able to do terrible things that would end the world. There is also a lot of potential benefit from AI — medical research, for example. What do you see as the optimal path forward? We are now in politics, it’s not a completely rational world any more.

EY: All of this stuff is a risk: you can try to do the relatively less risky stuff, but it is still putting humanity in danger. If you believed what I believe, you would shut it all down. We have maybe got another five years.

JP: I don’t fully agree with your “shut it all down” — it’s not a position that we could get to. Is it better for us to try to have governments do this with limitations? Or do we need to be trying to steer private companies towards creating more interpretable types of algorithms that will be safer?

EY: I’m not going to ask governments to align AI [with human values], I don’t think even the private labs can do that. The reason why there might be some tiny shred of hope at this point in government action is that the thing I’m asking for is simple — back off and make sure everyone else backs off.

JP: I think that the national security world doesn’t think that OpenAI is the main threat — they think about China.

EY: China has, if anything, been more proactive about regulations [concerning AI] than the US. I would hope that if you go to China and say “Could we shake hands on not destroying the world,” that China would be willing to do that. I can give further details but people have been using other people’s threats for a while and when did China say: “Sure, we are going to drive ahead and destroy the world, don’t bother slowing down”? China has not said this.

JP: That relies on verification. They have to be very, very sure that we’re not doing it in some secret lab and we have to be very, very sure that they are not doing it in some secret lab, and China is not a country that is easy for us to verify things in — just look at Covid — and I don’t see how you get to a position where that works. One solution could be to have something like a CERN [the European Organization for Nuclear Research] for AI, where you basically have transparency on both sides. We outlined this in the Blair-Hague report on AI. Working together to publicly invest in algorithms which are more interpretable would be a more practical step than trying to get everyone to stop in such a low-trust environment. Remember, the Chinese and the Americans are barely even speaking at the moment at government level, so the idea that we would be able to coordinate such a big thing seems very difficult to me.

EY: What do the US and China do if Russia says they are going to build GPT5? Or North Korea steals a shipment of graphics processing units (GPUs) [these dramatically speed up computational processes for deep-learning AI]? If you have got a coalition who have said in the name of humanity we are all backing off and then North Korea says “Well, we don’t care,” then you may have to launch a preemptive conventional strike on the North Korean data center.

JP: You wrongly assume we won’t learn anything about how to make superintelligence safe until the superintelligence has been built. We may learn a lot about how to do that before we arrive at something very dangerous that requires preemptive strikes.

EY: As smart as we are now, I think it is just too high of an ask to expect people to build the first really dangerous systems, the first super-intelligences, and not have everyone die several times along the way learning how to do it. You have got to crash some prototype planes before your first plane really flies and in this case the prototype plane has the human species on board and that’s always been the central problem.

JP: What event would make a shutdown politically plausible? Politics is driven by events, it is not primarily driven by reason.

EY: Either GPT4.5 comes out and it’s articulate enough and demonstrates enough in advance a desire to kill everyone or something that people realize what’s going on, or there is some sort of minor disaster in which humanity survives but which causes people to realize what’s going on. But mostly I don’t predict we are going to survive this. I don’t predict there is going to be some special event that makes everybody react appropriately. I predict we are all going to die, but it’s not my place to decide that humanity chooses to lie down and die.

JP: One pushback is that intelligence itself is not the only component of power. A collection of humans can be much smarter than any one individual and the way power operates, for example, in the military, is due to personal relationships: who is trusted by whom, who has physical access to what. So saying something is smarter than us doesn’t necessarily mean it’s able to take over.

EY: If you consider how humans took over a bunch of the world, it’s not that somebody else entrusted them with the sharpest claws or the strongest armored hides. Nobody gave us space shuttles, we built our own rockets. Instead of waiting to evolve sharper claws over a very long period of time, we figured out how to forge iron and build our own longer, sharper claws for ourselves. Expecting that an AI — which is something that is smarter than you, that thinks much, much faster than you — is going to sit around for a very long period of time waiting for you to entrust it with power, waiting for your slow hands to move, is the same sort of mistake as if you could have watched the rise of the hominids going: “But how are they going to take over the world when they don’t have very sharp claws?” The kind of AI I am worried about is not just smarter than humans but smarter than humanity.

The chess master Garry Kasparov played the game of Kasparov versus the world, which was around 30,000 people online coordinated by four chess grand-masters on the one side and Kasparov on the other, and Kasparov won. There have been some minor disputes about how fair that was, but the basic concept is that humans often don’t aggregate very well. This is why most major scientific discoveries in history were done by individuals like Albert Einstein — not a collective of 1,000 average people passing notes to each other who were thereby somehow able to do what Einstein did. It was Einstein. The brain in one place is stronger.

JP: Again, those examples are of intelligence but what I am referring to is power. Who is it that is sitting with the button that controls the nukes? Who is it that person trusts? There is more to power than just intelligence. Which rooms does the superintelligence not have the keys to get into? Now, you could say there are all sorts of ways round, that superintelligence could, in theory, get around these kinds of constraints. But nonetheless, humans have got quite a few ways of protecting themselves and it’s not apparent that simply being superintelligent will allow machines to immediately take over.

The security world has a lot of techniques for how they protect certain types of information and we can begin thinking about what kinds of things do we need to make sure that a superintelligence never knows — does it know about that kill switch [which switches it off] for example?

EY: How are you supposing that something vastly smarter than you does not know about the kill switch? There are no possibilities that you can imagine that it’s not thought of.

JP: It could infer there may be a kill switch. But knowing where it is and who controls it can’t just be inferred. Again, you can constrain things: if you had something that you thought was dangerous, you could restrict it. I studied motor control as a neuroscientist so I have thought a lot about how intelligence interacts with the world. You can put limits on that, such as limiting how much data it can communicate.

EY: If you are smart enough and paranoid enough to figure your entire species is taking these precautions, you are smart enough and paranoid enough to not build a superintelligence at all. You can pretend to yourself that you are going to keep the superintelligence in a box and not tell it anything about the outside world, expose it to no human text, try to prevent it from knowing humans exist, try to prevent it from knowing how its own hardware is specified. You can always fantasize stronger restrictions, but I don’t trust the bureaucracy to be exposed to something vastly smarter than them. If it’s that dangerous, you should not build it.

JP: A lot of human knowledge is through experience and experimentation in the real world. It doesn’t solely matter how smart the machine is, it has to be able to interact with the world in order to be able to pick up this knowledge. A superintelligence interacting in the real physical world isn’t going to have that, it can’t perfectly simulate what a whole civilization is like and learn to manipulate it, it’s going to have to try actually doing it to learn how, and we’ll be able to detect it doing that, right?

EY: Well, if you know what it’s doing, you can detect it. If it has managed to crack another system and build a smaller and more efficient copy of itself, then you are not monitoring what it is doing any more.

JP: From your line of reasoning, the only response is to shut everything down, but that’s simply not going to happen right now. Tell me, if you had a one-minute elevator pitch with the prime minister or the president about what you want to have done, what would you say?

EY: We have no idea how the stuff we’re building works, we cannot shape it very well, capabilities are running enormously ahead of our ability to shape behavior in detail. We have no idea what we’re doing and if we actually built something much smarter than us, everyone is going to die. We don’t know how fast capabilities are growing; nobody predicted in advance what GPT4 would be able to do after GPT3. They get unpredictable capabilities, unpredictable times. I cannot tell if we are three years off of doom or fifteen years off doom but we are plunging headlong into danger at an unknown pace and if we do this in actual real life, and stuff goes wrong the first time you try it, everyone is going to die. We need to back off, we need an international alliance, we need to track all the work being done, we need to have these machines only in licensed monitored data centers, and we need to approach this with an attitude of being terrified for our lives and the lives of our kids.

JP: I understand the worries about the risks, but I think we need to find a path forward that can navigate political reality. That may be the biggest challenge of our age. There is a strong chance that AI is a huge benefit as well, so it is obviously going to be a very interesting few years if we make it through. It has been absolutely fascinating to hear what you think and thanks very much for taking the time.

EY: We will see. Thank you.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.