Some readers have been asking me to comment on the latest London Bridge terrorism incident. And if I have some reluctance it is only because although ennui comes from writing the same article over and over again, that’s nothing like the feeling you get from writing the same article so often that you don’t even need to change the name of the location of the attack each time now.

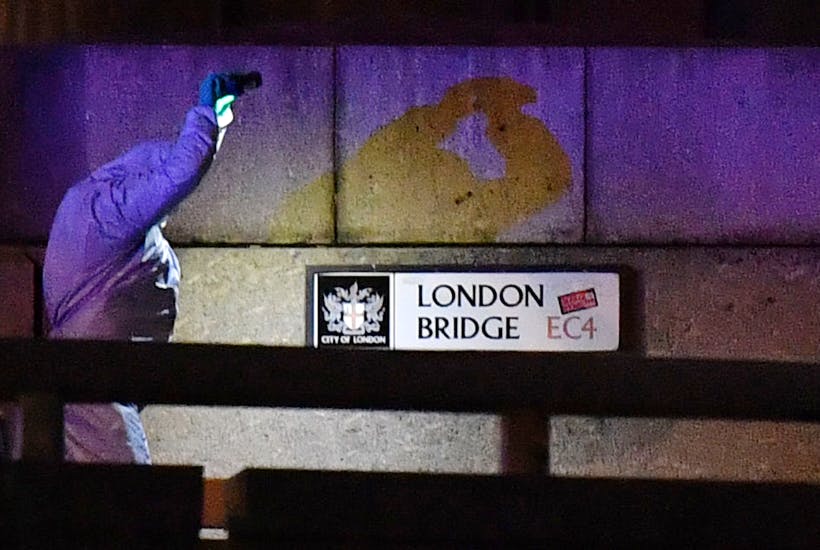

London Bridge 2 has been pored over enough in recent days. The heroism of certain members of the public has rightly been noted. Politicians of all the main parties have tried to pin the blame for the attacker’s early release on their political opponents. And everything goes on as usual.

But there are a couple of remaining things still worth noting about all this. The first is that if two innocent people hadn’t been killed and others wounded there would be something un-satirizable about Friday’s incident. A convicted terrorist is allowed out of prison after learning how to game the system, serves only half his sentence and then, at a prisoner rehabilitation session, goes full-crazy again and kills two of the young people involved in the rehabilitation business. The fact that the workshop Usman Khan was attending had one of those soppy modern Britain titles – ‘Learning Together’ – just completes the picture.

The problem remains that while we are happy to get caught up on discussions about prisoner release protocols and the like, we avoid the wider, and more skeptical, conversation we should have had by now. Conversations like the one we ought to have had about the whole de-radicalization business, or industry.

Here in October, I mentioned in passing the whole phony academic ‘discipline’ of ‘de-radicalization’. I wonder whether now mightn’t be a good time to reassess some of our reliance on the claims and expertise of that industry?

The truth is that as well as some good people, an awful lot of people have emerged in recent years, and a variety of organizations have been set up, claiming to be expert in this business. They claim to know how to ‘de-radicalize’ people and seek money from government, social media companies and others in order to develop this ‘expertise’ and sell it on for cash. The reason I have become increasingly skeptical about this whole business is not just because I think many of these people don’t know what they are talking about, but because the stakes are far higher than they like to remember.

Saskia Jones (23) and Jack Merritt (25) — who have been named as Usman Khan’s victims — appear to have been smart and idealistic young people. But they lived in a society in which the parameters of ‘radicalization’ (what causes it, and how it might be undone) had already been decided. People older but perhaps less wise than them decided to treat Usman Khan like any other prisoner and get him back into the community as fast as possible. And if there is anything to learn from the incident it shouldn’t be only a couple of narrow legal issues, but a consideration of whether we aren’t consistently hampering ourselves by deciding in advance what our problems can and cannot be.

The problem in countries like Britain isn’t just that we don’t seem to learn anything together. The problem is that we don’t seem to learn anything at all.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.