America is complicated. It’s hard to predict what it’ll do next, despite all the time and money spent observing it. Not without reason is Walt Whitman — with his long beard, loose morals and love of ambiguity — its national poet.

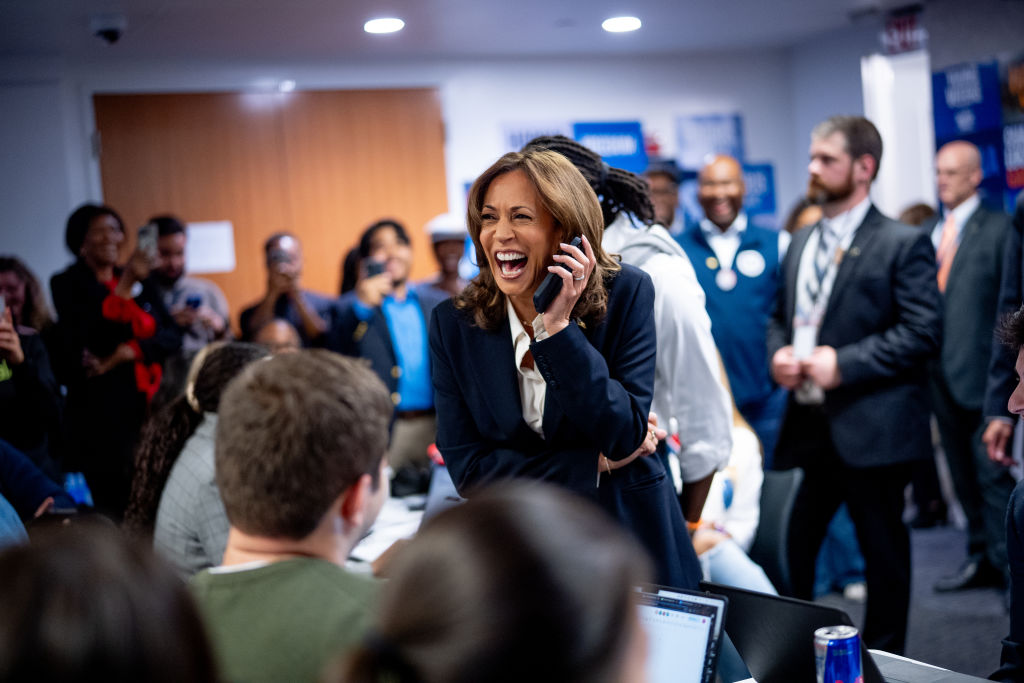

In an election year, plumbing the country’s mood is especially crucial. But that doesn’t make it any easier. Once bitten in 2016, the liberal portion of America’s establishment is twice shy, and terrified about slipping into the same complacency over Biden’s chances as it did over Clinton’s.

While not an American institution, the Economist fits neatly into the same footloose, cosmopolitan club as the more neoliberal-minded of Democrats. The paper’s 2020 election forecast, launched last month and updated daily until November, is a visually slick, apparent triumph of disinterested analysis. Based on hundreds of polls (and a lot of other data besides), graphs chart the changing potential spread of electoral college votes, the likelihood of each candidate winning each state, models of the potential popular vote, and the overall likelihood of who becomes president.

All very impressive, and most likely accurate. But why do it now, for this election? Why do quite this much? Buried between the charts and projections, and among the countless paragraphs detailing the project’s methodology in minute detail, is a deep, unshakeable anxiety.

The worldview the Economist exemplifies shattered the day Trump won the presidency. For all Biden’s late-developing radicalism, he’d still represent a soothing lurch back towards that status quo if elected. The obsessive number crunching and countless graphs are best thought of as an intellectual fidget spinner — a way of assuaging nerves by proving Trump’s electoral doom again and again.

The model was launched on June 11, when Biden had established a clear poll lead and an apparent 85 percent chance of winning. The days in early March, when the data begins and when Trump and Biden were trading polling supremacy, look like brief dogfights on the graphs, after which Biden sails serenely upwards and Trump drops lower and lower. A Trump second term is presented as a historical relic before the election has even taken place.

On one level, all these stats are a welcome contrast to the thick fog of misinformation that hangs around the current White House. Yet relying on it seems to misdiagnose the Democrats’ problem in 2016 — too much rationality and not enough emotion — as simply being that the spreadsheets weren’t big enough.

Data, as the pandemic has emphatically proved, is slippery to handle. Not only are we overwhelmed by the amount, but we never quite know if it is what it says it is. It emerged this week that Public Health England had been counting everyone that had had the disease and later died as a COVID-19 fatality, regardless of whether they had recovered from it and then succumbed to something else.

[special_offer]

James Bridle’s 2018 book New Dark Age explores how the exponential growth in recorded information leads to all sorts of dangerous presumptions. ‘Automation bias’ is one — we tend to trust conclusions reached by machines and algorithms, despite the fact that there’s always a fallible human writing the code somewhere. The paradox the Economist has to grapple with is that the more individual human responses they collate from polls, the more artificial processing is needed to combine them into something presentable.

Bridle describes the internet, the ultimate store of human-generated information, as a ‘hyperobject’: ‘a thing that surrounds us, envelops and entangles us, but that is literally too big to see in its entirety… Because they are so close and yet so hard to see, they defy our ability to describe them rationally.’

America, with its wildly varying geographies and culturally disparate inhabitants, could well be one as well. No one within it, from coastal elite to heartland patriot, can properly see the country in its entirety. Whitman’s over-quoted maxim — ‘I am large, I contain multitudes’ — should be taken to heart by the data-driven. There’s wisdom in contradicting yourself.