Beneath the polarized political spats that characterize the national conversation, there is a surprising degree of consensus between left and right on what is wrong with society. Selfishness, corruption, tribalism and a failure to build for the long term — these are universally decried. We can all see the same glitching appliances, but we seem determined not to follow the leads back to the same plugs.

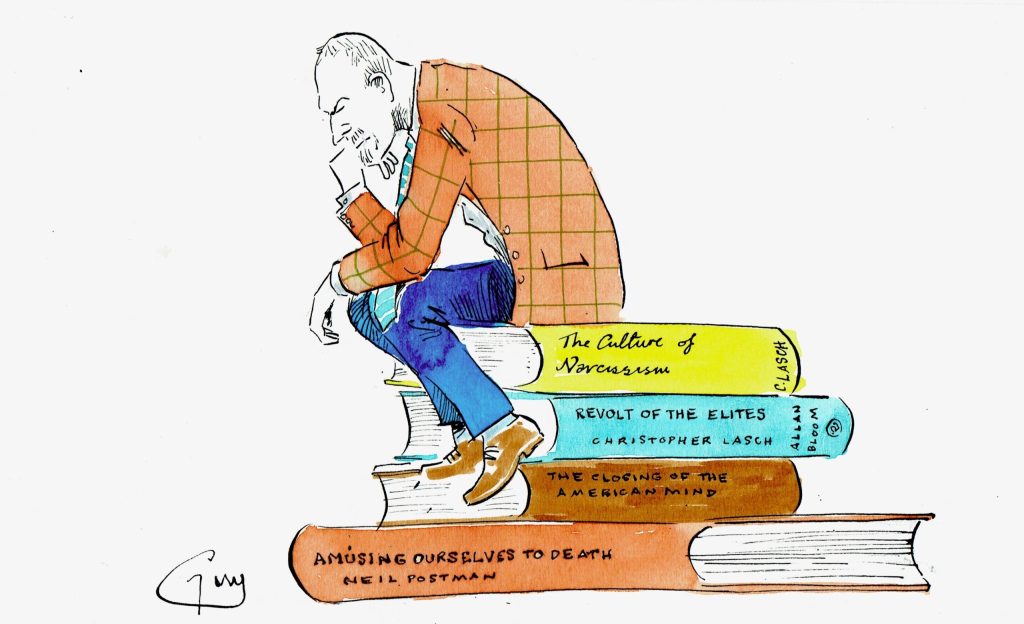

Occasionally thinkers appear that dig beneath the political fray and offer insight into how these political differences have come about. Three such writers that were published a generation ago, and have since been proved unequivocally right, are now available in my new preferred medium, the audiobook. I thought it might prove instructive to revisit them.

Christopher Lasch, a Nebraskan Cassandra who anticipated not only America’s coming woes but many of Britain’s, too, is perhaps the best of them. Lasch, a genial fellow who shared a room with John Updike at Harvard, made that familiar intellectual journey, exemplified by Christopher Hitchens, from neo-Marxist in his Sixties youth to sound good sense in his later years, before being cut off cruelly by cancer at just 61.

His breakthrough work, and still his best-known, was The Culture of Narcissism in 1979. If you wanted a primer to the era, a non-fiction counterpart to Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, you couldn’t do much better. And it is good to have narcissism discussed by someone who actually knows what it means, beyond ‘fancies himself something rotten’.

But for me it’s his last work, Revolt of the Elites, that resounds today. It is a well evidenced and elegantly argued defense of the traditional virtues of common decency, of laying aside gratification and putting your shoulder to the common wheel. It is Lasch’s suspicion that these traditional virtues were being eroded by a neoliberal meritocracy, which had somehow managed to subvert the original American Dream and twist it into something ugly instead.

For Lasch, the whole point of the Republic was that you didn’t have to be upwardly mobile, to deserve and demand respect. You earned it by fulfilling your role with diligence and humility, whatever and wherever it was.

The new elites, Lasch observed, ‘retained many of the vices of aristocracy without its virtues’ and had detached themselves from the great unwashed, both physically and in all legal and moral obligations too. Anyone who was paying attention four and a half years ago saw where that got them.

It’s the clarity and detail as Lasch recounts this gradual inversion of values that makes this essential listening, like finding cool clear water in a desert, or rather, in an overheated shopping mall.

Showing its age a little more, Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind was a huge hit in its day, rather confounding its author’s expectations and indeed his own argument, which was that the American public no longer had an appetite for this sort of thing. A Chicago professor’s detailed lament on the unwillingness of his students to engage with historical context and heavyweight philosophical debates — to think they know it all, in short — it is the kind of thing you might imagine David Starkey rattling off now, perhaps after being forced to watch something about the 1619 Project.

Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche and Max Weber get half a page each in the index, Jacques Derrida and the Buddha get a single entry each. But it is well-suited to the audiobook format as you can mentally skim when it gets too heavy and still benefit from something very close to the reading that Bloom denounces ‘kids today’ for being unwilling to do. If you harbor a suspicion that demands to ‘decolonize the curriculum’ are really just a cover for the age-old demand to make it easier, you will enjoy this.

Finally, Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman is a fantastic listen. Pithy, trenchant and furnished with vivid historical detail, it plays like a Town Hall address. Postman argues that serious debate has become impossible, as politics has devolved into a branch of show-business, due to our transition from a typographical society to a televisual one, obsessed with surface gloss. Writing in 1985, his Exhibit One was the presidency of former Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan. I doubt he would feel terribly reassured by the events of the last few years.

Quite where Postman would situate audiobooks on the text/TV spectrum I won’t presume to guess, but I’d argue, much closer to the former, and as capable of communicating complex thought, paradox and irony, nuance and precision as anything on the printed page. And with the speed function in play, you can easily get through Postman’s superbly pessimistic polemic in a single evening, before catching up with the latest on the 24-hour news channels in time to unsettle and disturb your ordered thoughts before bed.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.