America is a free country in which the law criminalises almost everyone. The web of nanny-state regulations and bureaucratic technicalities is so dense that anyone can be snared. The law criminalises far more people and far more activities than prosecutors can possibly tackle. So they act on their discretion, and that discretion is often informed by political considerations. Prosecute a high-profile figure, and you can present yourself as David slaying Goliath.Donald Trump’s frankly political pardon of Dinesh D’Souza—admirably frank, even—should be less cause for outrage than the use of prosecutorial power to score partisan points. Not that D’Souza was a hapless innocent caught in the complexities of U.S. campaign law. He has been involved in politics long enough to know full well that reimbursing friends for giving campaign donations to another friend is illegal. But the context matters, and the context here involves a U.S. Senate election in the state of New York, where the odds of D’Souza’s friend Wendy Long, the Republican nominee, winning against incumbent Democrat Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, were so slim as to be infinitesimal. D’Souza’s crime, which was real enough, was an act of misguided friendship, not a serious scheme to sway an election that his college pal was absolutely certain to lose by a landslide. The outcome, even with D’Souza’s illegal donation, was a Gillibrand victory of 72 percent to Long’s 26 percent. D’Souza received a punishment out of proportion to the magnitude of the crime: eight months of nightly detention in a halfway house, five years’ probation, and a $30,000 fine. Arguably, the case was not worth prosecuting at all, though one could say—and in other contexts, Republicans would say—that even inconsequential election-related fraud must be punished. In D’Souza’s case, however, prosecution was certain not because of the sanctity of our elections but because the prosecutor, Preet Bharara, was a politically ambitious Democrat eager to claim a prominent conservative’s scalp. Bharara would later be fired by President Trump, and now makes a living as a celebrity in his own right, as commentator for CNN. As the New York Times reported in September, “Rumours that Mr. Bharara may be considering a political career have also persisted, and his decision to take a role at CNN is likely to reignite speculation about his plans.” The writing has long been on the wall, right next to scalps like D’Souza’s.But by pardoning D’Souza, hasn’t President Trump politicised the process? The pundits who make this accusation are not being sincere—or if they are, their naivete is disqualifying. What Trump has in fact done is to make clear for ordinary conservatives and progressives how the already thoroughly political pardon power works. D’Souza is, if not exactly a household name, certainly well known to grassroots activists on both left and right. Marc Rich, by contrast, is someone most politically involved Americans had never heard of when he received a pardon from President Clinton on the latter’s very last day in office. Rich was a hedge-fund billionaire who owed some $48 million in taxes. He was charged with scores of other offenses and was a fugitive from justice. But through his ex-wife, Denise Rich, he was also a high-dollar supporters of the Clintons and the Democratic Party. As Time recounted, Denise “donated an estimated $1 million to Democratic causes, including $70,000 to Hillary Clinton’s successful Senate campaign and $450,000 to the Clinton presidential library fund. She also lobbied heavily for Marc’s pardon.”The Rich scandal resurfaced in late 2016, when shortly before the election the FBI released redacted files on the case. James Comey even makes an appearance—he prosecuted Rich at one point and later investigated the Clinton pardon. But Rich was hardly the only controversial last-minute pardon to issue from Bill Clinton’s pen: he pardoned or commuted the sentences of a variety of family cronies, left-wing terrorists, and jailed Democratic congressmen, including one convicted of soliciting child pornography. Wikipedia has a convenient summary here. Democratic presidents were not the ones to issue political pardons before Trump cleared the records of Dinesh D’Souza and Scooter Libby, of course. President George H.W. Bush pardoned a half-dozen figures in the Iran-Contra scandal. But what Trump is doing is not repaying hefty donors or wiping out a political embarrassment. Instead, with the D’Souza and Libby pardons, Trump has shown loyalty to conservatives who believed that these men had been wrongly prosecuted and punished. (The posthumous pardon of boxing legend Jack Johnson also deserves a mention here.) Trump’s critics believe he is also sending a strong signal to members of his own administration that he is willing to use the pardon to get them out of legal trouble, as long as they don’t cooperate with prosecutors. But there is another angle to consider: Trump is picking a fight with political prosecutors, starting with Bharara but likely extending to Comey. Trump has mooted the possibility of pardoning Martha Stewart for the dubious offenses—making misstatements to the FBI in a financial case—that Comey prosecuted her for. Trump is robbing prosecutors of their celebrity trophies. This is an affront to the entire ego-driven ecosystem of the ambitious prosecutor.There is politics throughout this story, but it doesn’t start with Trump: it is embedded in the way prosecutors have behaved for decades. They have tried to capitalise on popular resentment of the rich and famous, while also communicating to the public that they should be grateful to such mighty officials for mercifully refraining from going after every American businessman or car driver or other petty rule-breaker with the same zeal. Prosecutors are powerful people who appeal to the weak by making scapegoats of high-profile victims, though most victims of the legal system are the weak and obscure. Trump has turned the tables: he stands to win the public’s favor—certainly the favour of D’Souza’s grassroots fans—as a powerful man willing to stand up to powerful, arrogant prosecutors. Trump’s enemies believe he is entirely in the wrong. On the contrary: Trump is fighting a necessary battle, one that should lead not to outcry about political pardons, but reforms of and restraints on the abusive power of prosecutors.

Dinesh D’Souza’s pardon may be political, but that isn’t Donald Trump’s fault

The president is showing loyalty to conservatives who believe he was wrongfully prosecuted and punished.

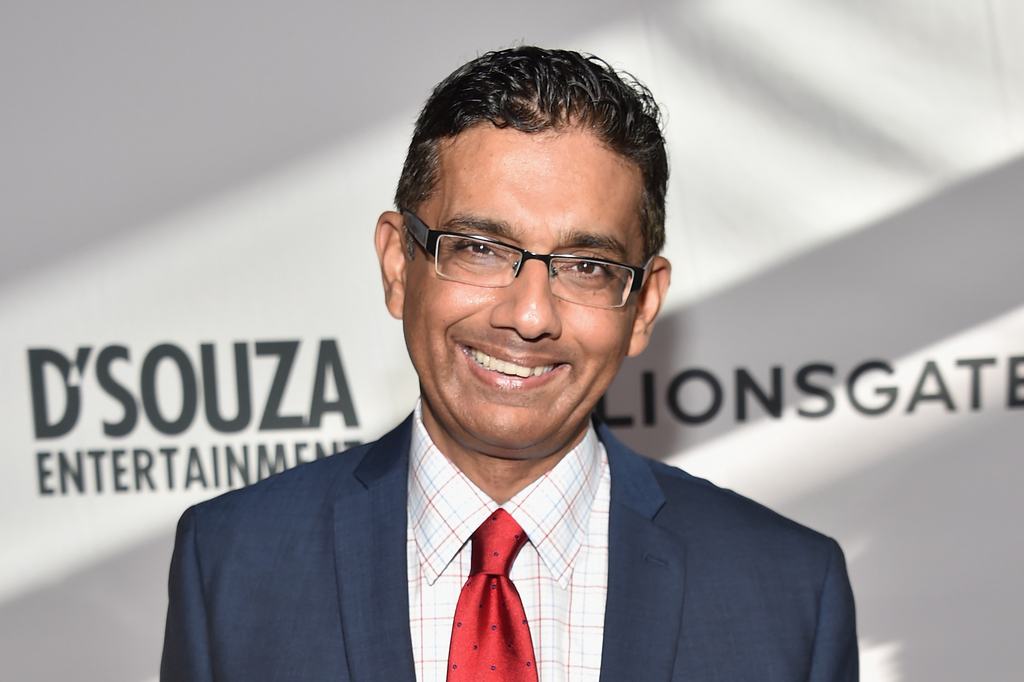

LOS ANGELES, CA – JUNE 30: Writer/director Dinesh D’Souza attends the premiere of Lionsgate Films’ “America” at Regal Cinemas L.A. Live on June 30, 2014 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images)

America is a free country in which the law criminalises almost everyone. The web of nanny-state regulations and bureaucratic technicalities is so dense that anyone can be snared. The law criminalises far more people and far more activities than prosecutors can possibly tackle. So they act on their discretion, and that discretion is often informed by political considerations. Prosecute a high-profile figure, and you can present yourself as David slaying Goliath.Donald Trump’s frankly political pardon of Dinesh D’Souza—admirably frank, even—should be less cause for outrage than the use of prosecutorial power to score partisan points….

Comments

Share

Text

Text Size

Small

Medium

Large

Line Spacing

Small

Normal

Large