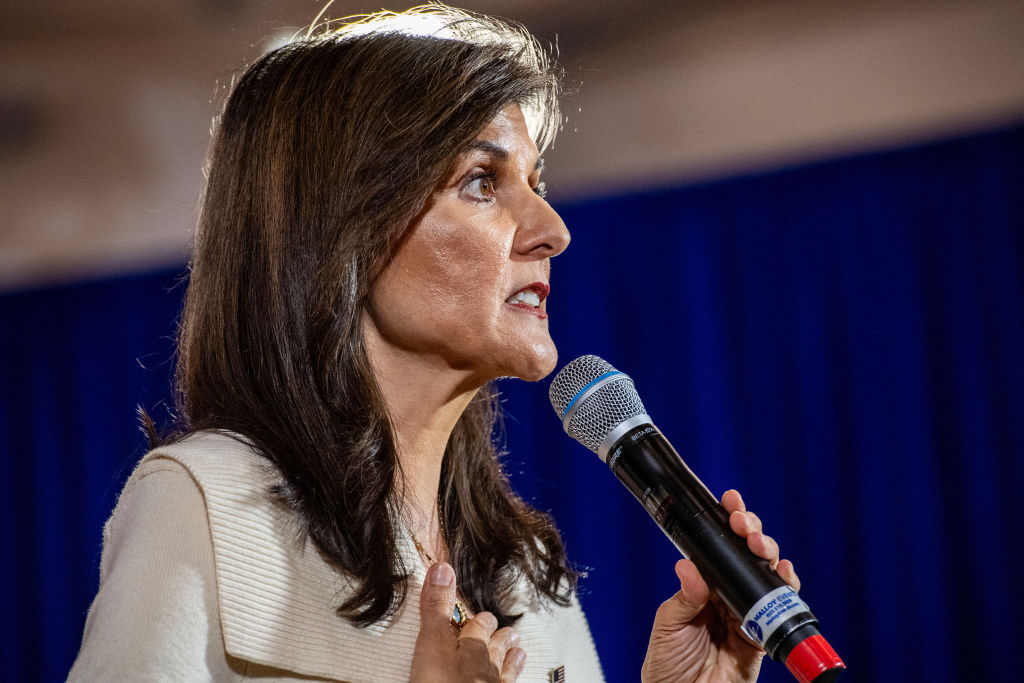

Nikki Haley reignited the battle over the cause of the Civil War.

Today’s racial protocol requires a reflexive one-word answer: “slavery.” Haley didn’t give that response, but neither did she give one that reflects our best historical knowledge. Instead, she blamed government for not ensuring “that individuals have the liberties so that they can have freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom to do or be anything they want to be without government getting in the way.” The media pummeled Haley.

In fact, the primary cause of the American Civil War was different from the pat answer. It was slave-produced cotton. Cotton and race-based slavery cannot be separated here. We need to consider them together because that is how they produced the most devastating crisis in our history.

It was the economics that made enslavement of African Americans intermittently very profitable in the ante-bellum South. Expectation of great wealth was firmly implanted. Social convention followed the logic of profitability.

The founding fathers understood the logic. They knew race-based slavery could not exist with that lucrative base. What blindsided them and their immediate successors was the unexpectedly swift rise in the scale and dreams of fortunes which swept the American South not long after the new nation was founded. That production was grounded in slave-based agriculture.

The facts are compelling. Cotton production increased from virtually nothing when the Constitutional Convention convened in 1787 to more than four and a half million (450-pound) bales per year on the eve of the Civil War. The insatiable demand by English textile mills wrought a revolution in hygiene and clothing. Southern planters met demand with enslaved workers, who planted, chopped and harvested the crops. That enslaved population quickly grew from 700,000 to approximately four million — the majority of whom were directly or indirectly involved in cotton production.

One indication of how closely slavery was tied to cotton is correlation of prices. The price of a slave went up and down with that of cotton. At ten cents a pound for cotton, slavery spread. When cotton was trading at four cents in the 1840s, the price of a slave plummeted. At two dollars a pound during the Civil War, the Union army was besieged by cotton-induced corruption. Another indicator is that slave prices rose when they were transported closer to cotton-growing regions. In the Deep South. That’s where they were most valuable. Finally, slavery only spread where cotton could be grown.

The connection between cotton and slavery was understood with special clarity by Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the most politically influential novel of the nineteenth century. There would be no support for slavery, she wrote, if “something should bring the price of cotton down once and forever and make the whole of slave property… a [burden] on the market.”

Of course, slavery in America long predates the rise of cotton and the political divisions that led to the Civil War. But the long history shouldn’t blind us to the fact that slavery, as an institution was precariously balanced on the fluctuating market price of cotton. Cotton was subject to volatile price swings and the South’s slave-based economy rode a roller coaster with it. The derivative relationship meant that the institution of slavery had a solid base only if cotton was profitable.

Why didn’t Southern planters simply turn to other crops? Because only slave-produced cotton had such high potential profit. Slave-produced cotton could be easily grafted onto the existing plantation. In time, it came to dominate that system.

True, other forms of slave-related agriculture and industry did exist in America, but they were either small or lacked significant export potential. Not so for cotton. It was the country’s leading export from 1803 until 1937, except for a few years during the Civil War and immediately after.

The use of slaves on plantations dwarfed its use in industry. In Richmond, for example, the Tredegar Iron Works employed eighty slaves out of 800 employees. In any case, iron works like that, and the use of enslaved workers within them, couldn’t compete with factories in the Northern states or Europe that relied on wage labor. Other possible slave-related schemes suggested are mere uninformed speculation given political context or economic viability.

Economists and historians sometimes miss the essential point about the limits of employing slaves profitably. So did the proponents and opponents of slavery in the 1850s. Grandiose Southern rhetoric about the expansion of slavery to the Midwest, Far West, or abroad had a huge political impact at the time. The battle for Kansas may have been bloody, but it was economically impractical on a large scale without the ability to grow cotton.

Understanding this role played by slavery is crucial to our comprehending our country’s history. But the exclusive use of racial lens to interpret the past distorts reality and harms us now by buttressing our attachment to racial separatism and ethnic divisiveness. That’s why it is wrong to trot out pat questions and answers and use them for litmus tests. That happens all too often to our detriment. If the question is what caused the Civil War; the required scripted answer is “slavery,” a purely racial phenomenon. A more accurate answer is slave-produced cotton.

It is probably too much to ask political candidates to avoid non-objective narratives in dealing with polarizing issues like this. Their goal is not to uncover some deeper historical truths but to use polarization to increase their partisan base. Still, it should not be too much to ask candidates who seek to lead our country to take our history more seriously and to use it constructively to address America’s divisions which are arguably as dangerous as those leading to the Civil War.

Gene Dattel is the author of Cotton and Race in the Making of America and Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure.

Leave a Reply