This week, a malign foreign actor invaded the British media, spreading disinformation and seeking to meddle in the general election. A malevolent force exploiting our democracy to advance its own interests. That’s right, Hillary Clinton has been in London. She has another book to promote, The Book of Gutsy Women, and she’s again talking about male authoritarian-ism, why Britain needs to be ‘forward-looking’ (i.e. not leave the European Union), and the menace of Russia. It doesn’t take an intelligence expert to decode her message: ‘I didn’t win in 2016 and I’m still livid.’

Clinton says she is ‘dumbfounded’ that the British government has decided not to publish a parliamentary report on Russian meddling in UK politics until after December 12. ‘Every person who votes in this country deserves to see that report before your election happens,’ she says. ‘I find it inexplicable…and shameful.’ She may have a point there: some funny politics are being played about the report’s publication. But it’s hard to take her seriously on the subject because poor Hillary has succumbed to Russia Derangement Syndrome: a malady that means you see the hand of Moscow everywhere.

She fully believes that Vladimir Putin played a decisive role in her losing to Donald Trump. Last month, she called the Democratic presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard a ‘Russian asset’. She offered not a shred of evidence to back up the claim, but she does have evident animus. Back in 2016, Gabbard supported Bernie Sanders above Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. Gabbard must be a Putin plant, then.

That’s the trouble with a lot of the talk about Russia. It boils down to highly political people saying: if you are against us, you must either be for Moscow or one of those poorly educated digital troglodytes manipulated by Vlad’s social-media trolls. The Russia-did-Brexit idea has been floating around since at least June 2016. As conspiracy theories tend to do, it intertwines neatly with the other big one: that Russia hacked the American presidential election for Donald Trump. Both theories involve pro–Kremlin online bots, ‘concerted’ dis-information campaigns, and allegations of corruption. Trump had an interest in building a tower in Moscow; the Tories did fund-raising events with Russian oligarchs. Kompromat! What more do you need?

How about proof that Russian activity changed the minds of voters? There have been plenty of governmental and journalistic enquiries searching for such evidence. Embarrassingly little has been found. Yes, pro-Brexit or pro-Trump messaging emanated from the Internet Research Agency, that notorious troll factory in St Petersburg. It might be a good idea to try to stop that happening again. But does it explain Brexit? Or Trump? No.

Rather than confront this awkward point, Russia Derangement Syndrome sufferers double down. Like 9/11 truthers, or millennium apocalypse theorists, they come up with ever more wild ideas to validate their position. They claim, for instance, that Russians agents are everywhere. Last year, the Henry Jackson Society claimed that Moscow had 75,000 spies in London — that’s half the city’s Russian population.

Russia didn’t just hack the referendum, these paranoiacs say: the Kremlin may now be running Britain. Emily Thornberry, the shadow foreign secretary, recently wrote to Dominic Raab to express her concerns over Boris Johnson’s adviser Dominic Cummings’s connections to Russia. She asked about his links to ‘Oxford academics’ who knew about Russia, his relationship to the Conservative Friends of Russia Group, and his time working in Moscow between 1994 and 1997.

It’s worse than you think, Emily. The Spectator can further reveal that Dominic Cummings didn’t just live in Moscow during those years — he shared a flat with Liam Halligan, the Sunday Telegraph journalist and author of Clean Brexit, that influential pro-Leave tract. ‘It was the mid-Nineties,’ Halligan admitted this week. ‘I got a fax from [the late Oxford Professor] Norman Stone about a brilliant young graduate who was looking to come to Russia. So I gave him a sofa to sleep on in my old, Brezhnev-era flat. The next thing I knew he was running a bond desk and trying to launch an airline.’

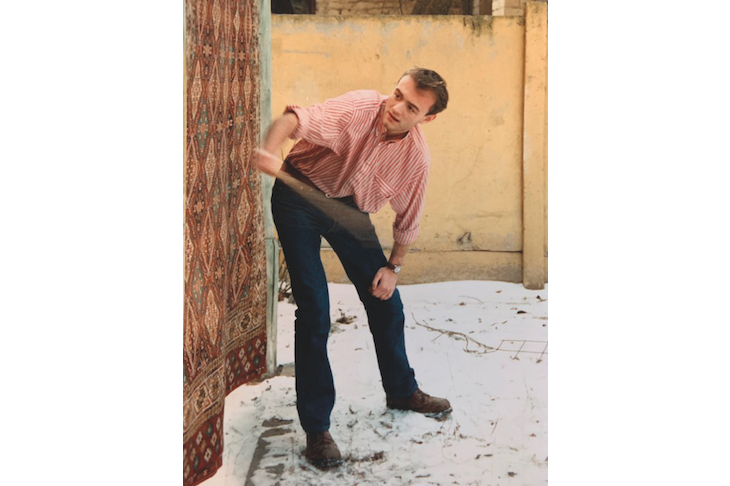

This, surely, is the moment Brexit was born. Halligan gave this magazine a picture (see above) of Cummings from that time, fascistically beating the dust out of a rug. Halligan confirmed that other influential figures were in Moscow in those years, including Michael Ellam, the Director of Communications at 10 Downing Street under Gordon Brown, and Peter Orszag, who went on to be an economic adviser to Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Does Hillary know about that?

‘Moscow was really buzzing back then,’ said Halligan. ‘There were all these young westerners out there who were interested in politics and economics in that fascinating moment after the Cold War. This was history on speed, and loads of bright people were drawn to it. There’s nothing sinister about it.’ Well, he would say that wouldn’t he?

Thornberry was probably briefed on Cummings by one of those intelligence goons who gravitate between security, political and hedge-fund circles. These people, some of them MPs, spread outrageous claims as if they were obvious truths.

For instance, Brexiteer Jacob Rees-Mogg must be a Putin operative because Somerset Capital, the emerging markets fund he founded, has invested in Russia. Another anecdote in Westminster is that Nigel Farage himself smuggled two thumbnail disks containing Hillary’s emails out of the Ecuadorian embassy in London after meeting Julian Assange, then passed them on to Donald Trump.

These rumors are not much more credible than the ones you hear about the Clintons running pedophile networks from the basement of a pizza parlor. The big difference is that the anti-Clinton theories are circulated by loonies on right-wing message boards and widely mocked. The Russia stories are said at smarty-boots parties and everybody nods along.

The more curious aspect of Russia paranoia is that it ends up achieving precisely what Putin wants. It gives the world a vastly inflated sense of Moscow’s strength. Russia’s GDP is considerably smaller than Italy’s. Yet we are led to believe that, with a little online legerdemain and a few bribes, its president can decide who rules America and who is part of the European Union.

That’s why Russian intelligence officials tend to tell suspicious western journalists exactly what they want to hear. It makes the Kremlin seem far more powerful than it is. In their shoes, wouldn’t you do the same?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.