Mark Zuckerberg is in a lot of trouble. He has turned away from the slog of running Facebook to focus almost entirely on his “metaverse,” a vision of the internet where people enter interactive virtual spaces using virtual reality headsets. He has pledged investment of at least $10 billion a year for a decade, and investors have been told that profits will be lower for the next decade as a result. He saw the digital future once. Can he repeat the trick?

Right now, it seems not. His company’s stock price has more than halved, wiping $600 billion off its market value. Shareholders are worried. Meta is to cut expenses by at least 10 percent in the coming months, in part through redundancies. More cuts are expected.

Last week’s Meta conference — held in the metaverse, aptly enough — failed to change the mood. The announcements of a $1,499 VR headset and the dramatic introduction of legs for metaverse avatars did little to convince the markets this really is the future: Meta’s share price is down almost 25 percent just in the past month. Zuckerberg’s personal wealth has shrunk by more than $76 billion this year so far.

There’s an obvious problem with Zuckerberg’s vision: who wants to wear a clunky virtual reality headset, watching outdated graphics that induce nausea? In a world where most of us use the internet via our mobile phones, can this really be the future? The figures suggest not: Meta expected 500,000 active monthly users on its VR platform, Horizon Worlds (which is accessed by VR headsets), by the end of this year; the current figure is fewer than 200,000. Leaked internal documents show that most of those who visit Horizon tend not to return after the first month. Meta staff themselves are reportedly unsure of the product: “The simple truth is, if we don’t love it, how can we expect our users to love it?” wrote Meta’s metaverse vice-president Vishal Shah in a memo last month.

Even the small slice of people who think the metaverse is the future don’t want Zuckerberg in their club. The metaverse isn’t meant to be dominated by a handful of tech giants in the way that has happened to social media. The utopian idea — known in Silicon Valley as “Web 3.0” or Web3 — is decentralization, helped along by technologies such as crypto-currencies and blockchain. The man who came up with the term “metaverse,” the sci-fi author Neal Stephenson, is in fact part of a rival virtual reality team producing “THEE METAVERSE,” to be powered by blockchain. There are many others.

Despite this, Zuckerberg is betting his house on the metaverse: Meta employees tell me he has all but clocked out of running the embattled Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. Why worry about fixing their issues if the end goal is to make them obsolete?

Facebook may have been passé for a decade or more now, but until recently it maintained an impressive revenue stream thanks to a somewhat dubious bit of activity tracking across cell phones: if you had the Facebook app, it could see elements of what you did outside that app. This provided useful information for advert targeting, on Facebook and elsewhere, keeping profits high for years. Then Apple introduced the option to “ask app not to track.” More than 97 percent of users opted out of ad tracking — and Facebook’s revenue took a huge hit.

Sometimes such companies appear too big to fail, but in the tech world, empires can crumble as quickly as they are built. Ask Rupert Murdoch: in 2005 he forked out $580 million for MySpace when it looked like the world’s hottest internet firm. Two years later, it had 300 million registered users and was valued at $12 billion. Yet it was overtaken by Facebook (launched a year after MySpace) and later offloaded to an online ad company for around $35 million. When users decide to ditch one platform in favor of another, change can be brutal.

Instagram is also tanking because of TikTok. Zuckerberg’s site recently tried to offer a TikTok-like feature of short video “reels.” This type of copycat tactic worked well for the company when Snapchat was the new rival. This time, though, such imitation didn’t go down well. Users — including the Kardashians — so hated the new TikTok-style feed that Instagram was forced to reverse the change. Meanwhile, the latest social media app to make waves, BeReal, has billed itself explicitly as the anti-Instagram option. It sends a notification at a random point in the day demanding you post a picture of whatever you’re doing. The spontaneity is a reaction to the excessive editing of Instagram posts.

Despite his unpopularity among tech figures, Zuckerberg looks set to leave all of this behind in his move to the metaverse. The big question is whether he can build something responsibly. What’s to say that the metaverse doesn’t become a way to be abused and sexually harassed in virtual reality? The Wall Street Journal recently reported that when one of their female reporters visited one of Horizon’s most popular virtual worlds, the Soapstone Comedy Club, she was asked by a user in the virtual room to expose herself. With a user ratio currently of one woman to every two men on Horizon Worlds, this sort of behavior is likely to be quite prevalent.

Facebook’s problems are widely known, from child pornography to jihadi material to election interference and everything in between. Last month, Amnesty International called on the company to pay more than $150 billion in compensation to Rohingya Muslims for propagating hate speech in Myanmar. That wasn’t the only headache for Zuckerberg, either. In the same week, Instagram came under the spotlight during the inquest into the death of the British teenager Molly Russell. The fourteen-year-old left an Instagram post that said “I’m just not good enough” before taking her own life in 2017. Her family argue that the content that she saw on Instagram depicting self-harm and suicide “influenced” her actions. The coroner recorded it as “an act of self-harm while suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content.” Instagram’s head of wellbeing, however, rather boldly claimed that the content Molly viewed was safe for children.

On the surface, WhatsApp might look like a simpler proposition. But that app, which Zuckerberg bought for just under $20 billion eight years ago, is also causing problems, both financially (he hasn’t found a way to monetize it) and politically (end-to-end encryption has led to friction with governments worldwide).

Meta employees I’ve spoken to say they despair that their boss has checked out from his three apps and isn’t interested in suggestions on how to improve them. “It could be quite frustrating — we would be trying to point out what I think were reasonable and universal technological or logistical realities, but they would be almost ignored,” said one former Meta staffer who worked in Europe. Zuckerberg appears to be trying to do enough to look like he’s fixing problems, while really just shunting them away from himself. Nick Clegg’s role involves handling the politics for Facebook, while the company has set up an expensive independent oversight board to adjudicate its thornier moderation decisions.

Another issue Zuckerberg faces is that while once he was able to buy his dominance in the market, today he is stifled by competition authorities with a much better grip on just how big Meta is now. Such authorities are warier of Meta buying up potential rivals as it did with Instagram and WhatsApp. British authorities this week successfully challenged its purchase of the gif company Giphy, which is hardly a multi-billion-dollar powerhouse.

Zuckerberg is not yet forty years old — so it’s no surprise that even with his $50 billion net worth he doesn’t feel ready to retire just yet. There’s no one within Meta who could oust him by force, as his shareholding is too large. But while he still seems to need Meta — and still wants to have one more signature achievement of his career — it is increasingly clear that Meta doesn’t need him.

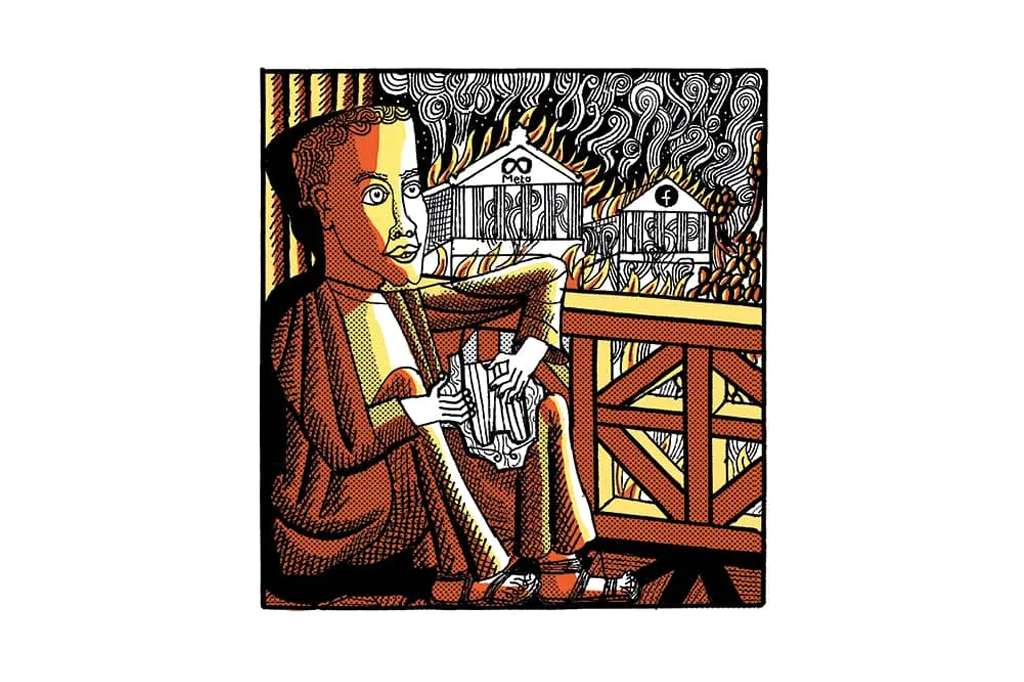

Four years ago, the Facebook founder revealed his admiration for Augustus Caesar. Zuckerberg honeymooned in Rome (his wife joked that Augustus was the third party on their trip), one of his daughters is called August, and his strange haircut is reportedly inspired by Augustus’s style. But as he fiddles in the metaverse, ignoring the fact that the rest of his empire is crumbling, he is beginning to more closely resemble Nero.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.