The law of political gravity favours the Democrats in the midterm elections less than two weeks away.

They will gain seats in the House of Representatives no matter what they do, barring an upset of a kind that has happened only twice in the last 80 years.

Curiously, both exceptions to the rule that the president’s party loses ground in the midterms were either side of the 2000 election. The Democrats under Bill Clinton picked up five House seats in 1998; the Republicans under George W. Bush gained eight in 2002. There were unusual circumstances at play in both instances: Republicans in 1998 were getting ready to impeach Clinton, while in 2002 the Bush administration was preparing for the Iraq War while the memory of 9/11 was still fresh in voters’ minds. Is the Trump administration such an unusual circumstance in its own right that it, too, will defy what is otherwise one of the firmest laws in American politics?

We’ll find out in a fortnight. But Republicans don’t have to win in order for Democrats to lose — if Democrats fall short of the just over 20 seats they need to gain to take control of the House, that will be a stinging defeat. And if Democrats do take control, then what? Will they capitalise on their power to set themselves up to retake the White House in 2020? They almost certainly won’t, because the Democrats are deficient in political entrepreneurs.

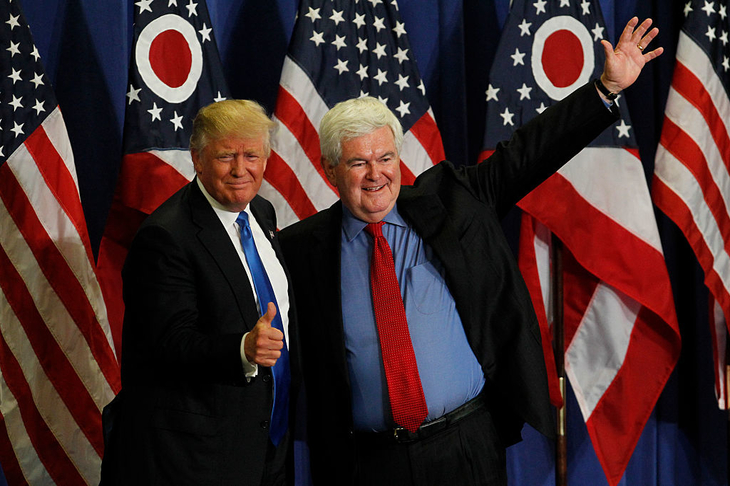

The Republican Party has produced three great ones in the last 40 years. Ronald Reagan was the first, Newt Gingrich the second, and today Donald Trump is the third. A political entrepreneur in this sense is someone who transforms a party ideologically or institutionally. They represent a break with the past, and with conventional rules. Reagan broke with the bland rhetoric and managerial practice of detente in foreign policy toward the Soviet Union. He ended the Keynesian consensus on economics at home. Supply-side economics was certainly a revolution in Republican economic thinking and muscled aside old Republican concerns about balanced budgets. In his relations with the Soviet Union, he did the impossible: he strongly spoke out against Communism and its oppression of Russians and the peoples of Eastern Europe — quite a change from the previous GOP president, Gerald Ford, who in a 1976 debate said there was ‘no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe’ — while also engaging in bold diplomacy with Mikhail Gorbachev. Reviled as a warmonger by the left, Reagan ushered the Cold War toward a peaceful conclusion. The outcome itself was hard enough for conventional political minds to imagine; the notion that Reagan would be the one to bring it about defied credulity. Yet Reagan proved the experts and elite wrong.

Gingrich may have dreamed of being as imaginatively transformative a leader as Reagan was. But his entrepreneurial talent in politics took another form: he was an institutional insurgent and revolutionary. Before Gingrich became speaker in 1995, Democrats had controlled the House of Representatives since 1931 with only two brief interruptions (in 1947-49 and ’53-’55).

The GOP’s House leadership had become accustomed to playing partner to conservative and moderate factions within the Democratic caucus, which they were happy to do rather than aggressively seeking to win a majority of their own. Gingrich was aggressive. He levelled ethics charges against the speaker of the House.

And he took advantage of a new technological development, C-SPAN broadcasts from the House floor, to draw attention to himself and his attacks on Democrats. Other Republicans took inspiration from his example. He remade the party’s attitude.

Gingrich remade Congress as well, not altogether for the better. Once he became speaker he changed the seniority system and introduced reforms that undercut the power of House committees and shifted the burden of responsibility for major legislation in the direction of House party leadership, including the speaker himself. This has made members feel less responsible for lawmaking, and without the discipline created by strong committees, speakers themselves have had a harder time exercising authority. The result has been speakerships like those of John Boehner and Paul Ryan — speakerships that speakers themselves have been glad to relinquish.

Of Donald Trump as a force of creative disruption in American politics, plenty has already been written. He does not respect the ‘norms’ of Republican ideology or professional campaigning or technocratic governing, and by revealing how hollow all those supposedly hallowed things are, he has transformed his party and the very practice of politics. He has brought back the campaign rally, turning what had been a dead ritual into an enliving experience. By returning the GOP to its roots as a nationalist party, he has brought about arguably the biggest ideological reorientation since Franklin Roosevelt made the Democrats the party of the New Deal. And every day he clashes with the machinery of technocratic administration. All of this, of course, is only a sample of the changes that Trump hath wrought.

Entrepreneurial leaders like these allow their party to do more than just live by the law of gravity — they make their own rules. Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by being anything but a conventional Republican, another Mitt Romney or Paul Ryan. Gingrich too had to innovate to gain power and innovated more in wielding it. Reagan rejected the constrained possibilities for economics and foreign policy that the mandarins of his age insisted upon.

These leaders created possibilities for their party — and at best, their country — to win where winning had before seemed impossible. In the last half-century, only one Democrat has done likewise: Bill Clinton. But Clinton’s entrepreneurship was above all personal: he did revise his party’s ideology, but in a direction that has proved dubiously sustainable. His Democratic Party was no longer a party of private-sector labour and optimism about government services. He was the president who declared, ‘The era of big government is over’ — a great slogan for a Republican, or for a charismatic Democrat in the boom times of the 1990s. In other circumstances, however, Clintonism, which is now the default mainstream ideology, has been singularly unsuccessful.

The same was true, in entrepreneurial terms, of Barack Obama. What did he change about his party or his country? Absolutely nothing, if truth be told, despite coming into office with majorities in both houses of Congress and much national goodwill at his back. Obama was unimaginative as a leader, and to blame the Republicans for that is just grasping for excuses.

Obama could have been stymied by Republicans in every initiative, as he largely was. Still the question remains, just what were those initiatives? What did he try to do that the Republicans prevented him from doing? Very little of any originality. His signature achievement when he had Democratic majorities in the House and Senate was to pass a national version of Mitt Romney’s Massachusetts health care scheme.

Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer are not entrepreneurial leaders, and neither are the Lilliputians already vying for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. For three years now, the Democrats have been running against Donald Trump — he defines them, just as he has redefined the Republican Party. That’s the achievement of an entrepreneur. The Democrats are just resellers, and that will cost them in two weeks’ time. They have the law of political gravity in their side, but not the entrepreneurial verse to make the most of it — or to make their own luck.