Los Angeles County has too many voters. An estimated 1.6 million, according to the latest calculations – which is roughly the population of Philadelphia. That’s the difference between the number of people on the county’s voter rolls and the actual number of voting age residents.

This means that LA is in violation of federal law, which seeks to limit fraud by requiring basic voter list maintenance to make sure that people who have died, moved, or are otherwise ineligible to vote aren’t still on the rolls.

Los Angeles County has made only minimal efforts to clean up its voter rolls for decades. It began sending notices to those 1.6 million people last month to settle a lawsuit brought by the conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch.

Los Angeles County may be California’s worst offender, but 10 of the state’s 58 counties also have registration rates exceeding 100 percent of the voting age population. In fact, the voter registration rate for the entire state of California is 101 percent.

And the Golden State isn’t alone. Eight states, as well as the District of Columbia, have total voter registration tallies exceeding 100 percent, and in total, 38 states have counties where voter registration rates exceed 100 percent. Another state that stands out is Kentucky, where the voter registration rate in 48 of its 120 counties exceeded 100 percent last year. About 15 percent of America’s counties where there is reliable voter data – that is, over 400 counties out of 2,800 – have voter registration rates over 100 percent.

This echoes a 2012 Pew study that found that 24 million voter registrations in the United States, about one out of every eight, are ‘no longer valid or are significantly inaccurate’ – a number greater than the current population of Florida or New York state.

Pew’s total included at least 1.8 million dead people and another 2.75 million Americans who were registered to vote in at least two states.

In sum, America’s voter rolls are a mess – and everyone knows it. While voter registration rates over 100 percent are not proof of fraud, they certainly create opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t exist, such as voting twice in different precincts or the potential for requesting and filling out invalid absentee ballots. At a time when both parties are warning of threats to free and fair elections, obeying federal law by updating the voter rolls would seem to be an easy fix.

Instead it has become a hot-button issue involving the tension between efforts to expand ballot access and those aimed at securing ballot integrity. The most contentious example occurred in Georgia’s 2018 governor’s race, where Democrat Stacey Abrams has still not formally conceded to now-Gov. Brian Kemp, because during his tenure as secretary of state, she observed, ‘more than a million citizens found their names stripped from the rolls.’

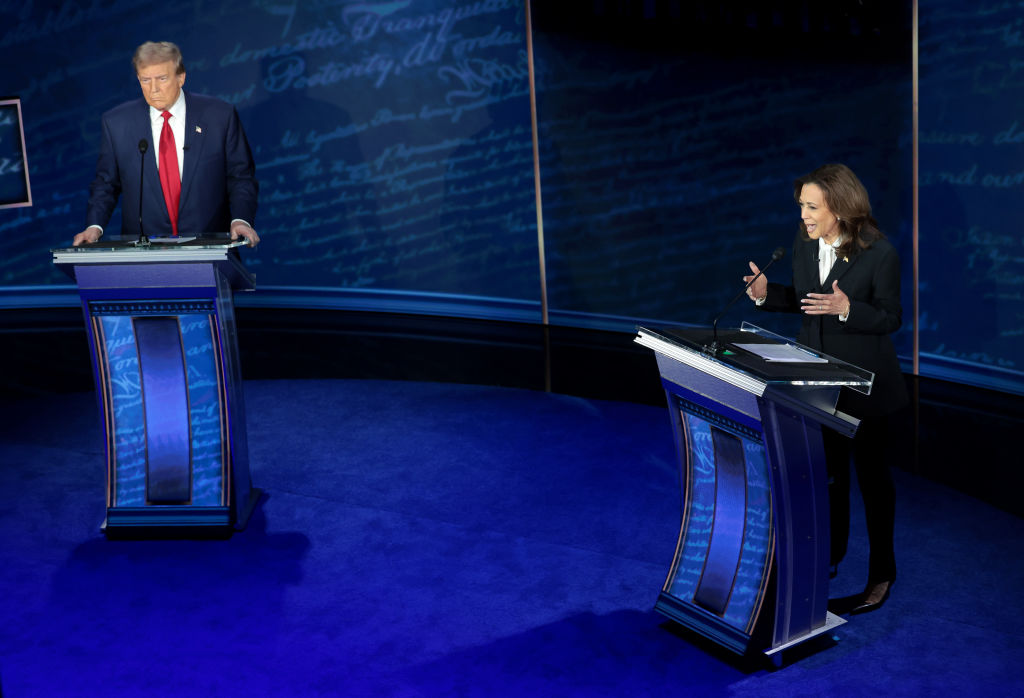

Abrams’s claim that the election was stolen from her has been repeated by many top Democrats including Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, and Pete Buttigieg.

Kemp did remove 1.4 million people from the voter rolls, though no evidence of wrongdoing has emerged. Last year, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution tried to contact 50 randomly chosen names purged from Georgia’s voter rolls. ‘Twenty clearly would be ineligible to vote in Georgia: 17 moved out of state, two were convicted of felonies and one had died. Most of the rest left a trail of address changes and disconnected telephone numbers,’ the paper reported.

It is, of course, likely that some number of eligible voters were included among those 1.4 million Kemp removed from the rolls – every human activity has an error rate. But experts say such problems are only compounded when states and localities disregard federal law mandating voter list maintenance.

Although the issue has become politicized, the counties and states where voter registrations exceed 100 percent represent a wide cross-section of urban and rural counties, as well as areas dominated by Republicans and Democrats. Much of this is simply the result of negligence in keeping voter rolls up to date, but a number of state and local governments appear to have left that work undone willfully and along partisan lines.

The National Voter Registration Act

The tension between ballot access and ballot integrity was clear in 1993 when Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) – sometimes colloquially known as the ‘Motor Voter Act,’ because its best-known provisions enabled people to register to vote at the DMV.

However, streamlining the process to bring in millions of new voters also increased the likelihood of inaccurate voter rolls. The Census Bureau, for example, reports that 11 percent of Americans move each year. People are far more likely to register to vote in their new homes than to alert their old communities that they have moved.

Accordingly, Section 8 of the law requires states to perform voter registration maintenance. While states have some discretion in initiating the process, the NVRA lays out a specific mandatory procedure for removing someone from the rolls. Essentially what’s supposed to happen is this: If the state suspects that a voter registration is no longer valid, it sends a notice requesting verification.

If voters don’t respond to the letter, they are listed as ‘inactive.’ Being designated as such presents no obstacles to voting. In fact, casting a vote automatically removes someone from the list of inactive voters. Per the law, the only people who can be removed from the rolls are those who fail to respond to the letter and do not vote in the next two federal elections.

Since passage of the NVRA, many states have simply ignored the maintenance requirements while others have sought legal workarounds. Robert Popper, a former deputy chief of the Voting Section in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, who now works on voting issues for Judicial Watch, said the most aggressive efforts have been led by Democrats. ‘The willingness of Democratic administrations to just make war on the NVRA is appalling,’ said Popper, whose group sued California over its voter roll failures.

In 1998, California got authority from Clinton attorney general Janet Reno to reinterpret the NVRA. The state decreed that ‘voters moved to the inactive file as a result of this procedure [the use of confirmation letters] shall not be canceled,’ according to a memo from California’s secretary of state in 1998.

In response, Congress amended the NVRA in 2002 through the Help America Vote Act. It clarified that the use of confirmation letters was a legal way to purge rolls. But it did not dictate how the states should keep rolls current. It just required them to have a process for ascertaining whether registrations are accurate, and to follow the NVRA process for removing voters who do not meet those requirements. In practice, many state and local governments used this discretion as a license to do little if anything. California, for example, has made minimal efforts to maintain its voter registrations since arriving at its interpretation of the law in 1998.

California’s secretary of state’s office did not respond to a request for comment, but a spokesman recently told the Daily Signal that Judicial Watch is ‘deliberately distorting this settlement to undermine voter confidence in democracy.’

California is hardly the only place in America where partisanship is blamed for lack of enforcement of the NVRA. According to Popper, Kentucky’s problems started in 2012 with the election of Democratic secretary of state Alison Lundergan Grimes. ‘At that point, by all accounts, they simply stopped designating people inactive and removing them after two general federal elections,’ says Popper. ‘I mean, just flat-out stopped. And that’s going to screw with your voter list.’

The days of ignoring or misreading the NVRA may be coming to end. Last year, the Supreme Court ruled in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, a case challenging Ohio’s voter maintenance laws. At issue was the state’s sending of confirmation notices to verify the registrations of citizens who hadn’t voted in while.

The high court ruled that the act of not voting was an acceptable trigger for deciding to verify someone’s voter registration. Not only that, the ruling was explicit about the intent of the law’s provisions to keep voter rolls accurate.

The effects of the decision were felt almost immediately. On July 16 of last year, just six days after the Husted decision came down, a federal court judge issued a consent decree requiring Kentucky to remove ineligible voters from its rolls, in response to a 2017 lawsuit brought by Popper and Judicial Watch. It was also the impetus for the settlement with Los Angeles County earlier this year, which itself had been sued by Judicial Watch on behalf of four local residents.

Asked for comment, the Kentucky secretary of state’s office drew attention to a need for adequate funding. In the consent decree, its statement said, ‘the Department of Justice and Judicial Watch both rightly recognize maintenance of Kentucky’s rolls requires proper funding and due process’ and that ‘since 2012, despite budget shortfalls, Kentucky has followed the law and properly removed over half a million voters from its rolls.’

No federal enforcement

Judicial Watch’s role in demanding enforcement of federal law raises another important question: Where has the Justice Department been? With a small number of lawsuits, Judicial Watch has arguably done more to enforce federal voter integrity provisions in the last couple of years than the DoJ has in the last couple of decades.

‘[There’s] a cottage industry now of private enforcement of Section 8 of the NVRA that has arisen from the Justice Department’s utter failure to enforce this federal statute,’ notes Popper. The Trump administration Justice Department joined Judicial Watch’s already-in-progress Kentucky lawsuit, but before that, the last Section 8 election integrity action brought by the department was a decade ago – initiated by Popper when he worked in the Bush administration.

The Obama DoJ did so little to enforce the law that that Justice’s own office of the inspector general investigated the matter. Its report presented evidence that former Obama deputy assistant attorney general Julie Fernandes said at a July 2009 meeting that Section 8 cases should not be brought. The report stated:

‘Thirteen witnesses told the OIG that Fernandes stated that she “did not care about” or “was not interested” in pursuing Section 8 cases, or similar formulations. For instance, Chris Herren, who was later promoted by current division leadership to section chief, told the OIG that Fernandes made a controversial and ‘very provocative’ statement at this brown bag lunch. In particular, Herren stated that Fernandes stated something to the effect of ‘[Section 8] does nothing to help voters. We have no interest in that.’ … Ten attorneys who attended the meeting told the OIG that they interpreted Fernandes’s comments to be a clear directive that division leadership would not approve Section 8 list-maintenance cases in the future.’

The IG report notes that some DoJ employees, as well as Fernandes herself, dispute that account of what was said. Whatever the true intent of Fernandes’ comments, the Obama Justice Department did not bring a single Section 8 list maintenance enforcement action during the entire Obama presidency.

Although the Trump administration joined the Kentucky case and in February brought an enforcement action against Connecticut, a total of two Section 8 cases don’t suggest the issue is a priority – even though the president has repeatedly expressed a desire to address the problem of voter fraud.

Asked whether the Trump DoJ is doing enough, a Justice Department spokesperson pointed to the Connecticut case and also noted a recent speech by assistant attorney general for civil rights Eric Dreiband, touting ‘important work on advancing our compliance reviews and investigations all around the country under all of our statutes.’

But despite the fact that federal law requires state and local governments to respond to regular surveys from the US Election Assistance Commission, it’s not unheard of for local governments to disregard them. Judicial Watch has had to sue for compliance on this issue as well.

In 2017, Judicial Watch sued Montgomery County, Md., to gain access to voter registration data it was refusing to release despite the fact the NVRA mandates that it be publicly available. Montgomery County has a voter registration rate exceeding 100 percent. Last fall, Maryland’s attorney general, Brian Frosh, put forth a remarkable court filing demanding that Judicial Watch ‘identify any Russian nationals or agents of the Russian government with whom you have communicated concerning this lawsuit.’ Judicial Watch responded that ‘Maryland officials are using a baseless allegation to retaliate against an organization and its supporters because of their conservative political views, a violation of the First Amendment.’

Maryland officials did not respond to requests for comment.

With hundreds more states and counties facing the prospect of cleaning up their voter rolls in the wake of the Husted decision, a lot more public angst over finally having to comply with the law is likely.

But Popper says the federal government and not a private group should be leading the enforcement work – namely ‘the 30 lawyers at the United States Department of Justice voting section where I used to work.’

‘I like to joke with people that [the NVRA is] one of the few instances of a federal agency undercutting deliberately the statute that gives it authority and power,’ Popper says. ‘You don’t find the Post Office undercutting the statute that, you know, authorizes the existence of the Post Office – but you find this with the Department of Justice.’

This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations.