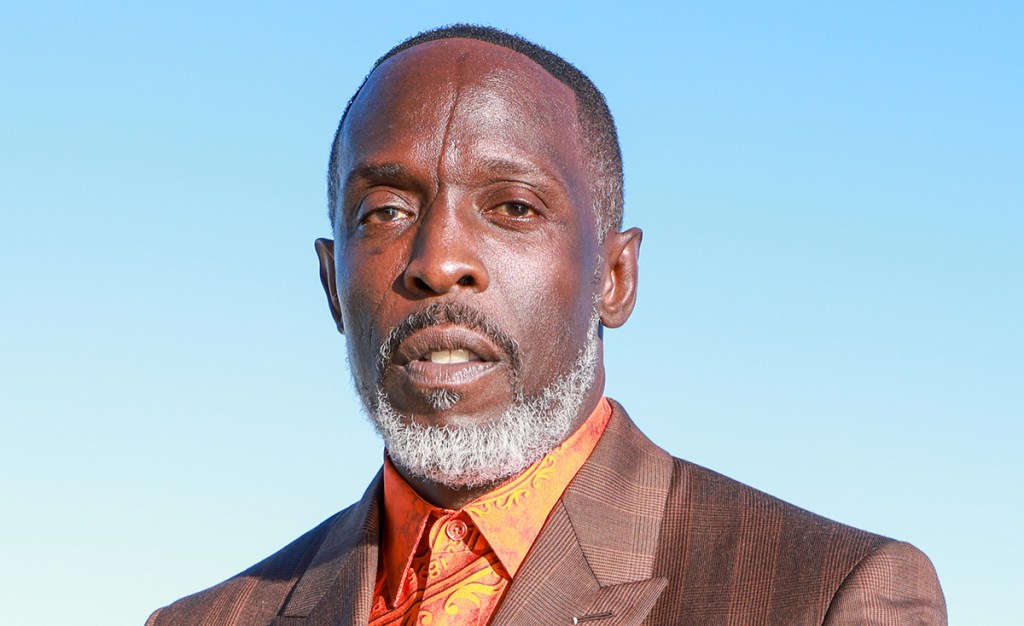

Did Chinese-manufactured fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, kill Michael Kenneth Williams, the actor who played Omar in The Wire? Within minutes of his death being announced on Monday, speculation was circulating on Twitter. New York Police Department sources have told the Daily Mail they suspect fentanyl was involved.

The world only seems to notice when a celebrity overdoses. In 2016, Prince’s death from a cocktail of fentanyl and other substances was an important milestone in awakening America to the horrific opioid drug epidemic that had crept up on the country since the 1990s.

But lots of non-famous people are dying all the time because of fentanyl from China, which has flooded the US drug market in recent years.

There is more than a little irony in the fact that the US is now on the receiving end of Chinese exports of synthetic opioids. In the first half of the 19th century, America sat on Great Britain’s coattails to become a major participant in the export of drugs to China. Whereas British opium was grown in Bengal and exported from Calcutta, America smuggled its opium to China from Turkey where US traders commanded a virtual monopoly.

Perhaps the greater irony is that it is Wuhan, the city whose name is synonymous with the origins of COVID-19, that is one of the major manufacturers of the opioids feeding the drug-death crisis that has ravaged the US for the last two decades.

Since 1999, the Center for National Health Statistics has calculated that opioid deaths in America have risen from 8,000 per annum in 1999 to 49,860 in 2019; in aggregate, over this period the opioid pandemic in the US alone has cost more than 500,000 lives. This compares with 630,000 deaths from COVID over the last 18 months. The average age of opioid deaths is about 40, however, compared to over 80 for COVID.

America’s opioid addiction costs over $1 trillion per annum, not including the cost of ‘long’ opioid addiction. Added to the drug deaths are the millions who continue to suffer from the effects of opioid addiction including the families of addicts. Opioids have caused social devastation in America particularly in the Trumpian ‘fly-over’ states of middle America.

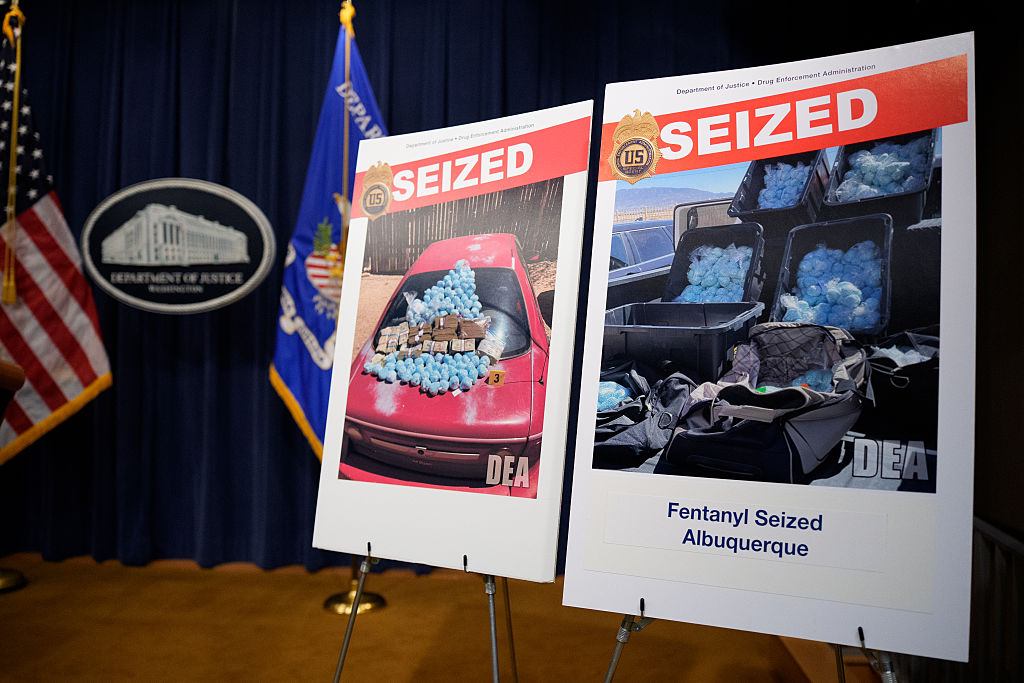

The rise of fentanyl can in part be explained by the ease of transport and distribution compared to the import of cocaine from South America. Until recently, online sales and the US Postal Service have done the job. The economics of fentanyl are compelling. According to the Drug Enforcement Agency, in 2017 a kilogram of fentanyl could be bought for $5,000 ($1,000 less than a kilogram of heroin) and, after being cut with agents such as talcum and caffeine, could be stretched to between 16 and 24 kilos; the profits can amount to some 20 times more than a kilo of heroin. Just two milligrams of fentanyl can produce a fatal overdose.

Like methamphetamine (better known as crystal meth), fentanyl can be cooked up in labs in poorly policed areas and transported anywhere. Although deaths from crystal meth took off at the same time as fentanyl in 2014, it registers just one-third of the deaths by comparison. Meanwhile, deaths for heroin and cocaine have flatlined.

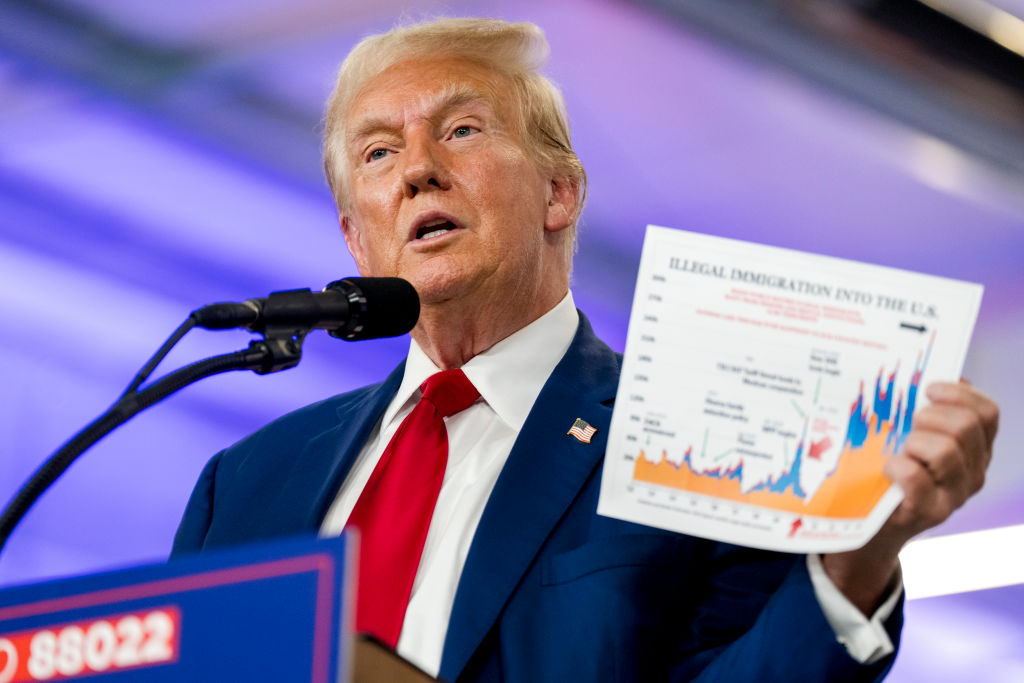

Not surprisingly, opioid manufacture in China is an embarrassment to Xi Jinping. There is nothing Xi likes more than lambasting foreigners for the 19th-century flood of opium and China’s subsequent ‘100 years of humiliation’ in the Opium Wars. Thus, when Trump requested that Xi shut down the Chinese manufacturers of fentanyl, the president seemingly scored a rare victory against his opposite number. Xi jumped to it, or perhaps just appeared to. He realized that criticisms of the West would fall on stony ground if, at the same time, China was pumping America full opioids.

Nevertheless, despite Xi’s crackdown, US drug deaths led by fentanyl hit a record 93,000 in 2020. Chinese manufacturers have become slier in their operations. In some cases, labs have been moved to remote locations or even overseas. Companies have started to supply fentanyl precursor chemicals or have developed unregulated derivative opioids. In 2017 only 19 of the 30 known analogues of fentanyl were designated as controlled substances under US federal legislation.

The Center for Advanced Defense Studies found 31 vendors were still selling precursor chemicals on Alibaba’s trading platform in 2019. A disgruntled Trump tweeted: ‘President Xi said this [the export of fentanyl] would stop — it didn’t’. In addition, new distribution channels have been developed, notably via the dark web.

In Europe, opioids have yet to reach pandemic levels. However, there are hot spots, which include the Netherlands and Estonia. To the embarrassment of first minister Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland has an opioid death rate almost 13 times higher than the European average. Neither is England likely to escape the opioid pandemic. There is alarm that traces of carfentanyl, an opiate 100 times more powerful than fentanyl that is used to tranquilize elephants, have been found in the north of England’s drug chain.

In Asia, as in America, the social consequences of the opioid pandemic are catastrophic. In the Philippines, where Rodrigo Duterte came to office on a populist pledge to deal with the exponential growth of drugs and the crime gangs that peddle them, dealers have faced widespread extrajudicial murder by death squads. By some tallies, as many as 20,000 Filipinos have been killed for their drug links.

When asked by Trump about the drug problem in China, Xi replied, ‘We give the death penalty to people who sell drugs. End of problem.’ Except it’s not. Since 1999, the official number of drug addicts in China has risen from 150,000 to 2.5 million while independent experts suggest that the real number is at least five times higher. Statistics on the level of opioid death in China are not readily available but it seems unlikely that the country has escaped the opioid blight.

Does the opioid pandemic have an impact on the COVID epidemic? Early studies suggest it does. Last October an article in Molecular Psychiatry reported that an analysis of 73 million patients at 360 hospitals in the US showed that drug users were not only at higher risk of contracting COVID but were suffering worse consequences as well. Opioid users are 10 times more likely to have had COVID than other types of drug users.

While vaccines may one day eradicate COVID, the prospect of ending the opioid pandemic seems far less likely. It is a sobering thought that over the long-term the Wuhan-derived opioid pandemic may well prove a greater killer than COVID-19.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.