The governor of the Mexican northern state of Durango Esteban Villegas announced last Monday the first “grand investment of the year.” The investment is of close to $400 million — and the investor is China.

This project is one of many. So it appears shortsighted to celebrate Mexico surpassing China to become the US’s top trading partner as an absolute “decoupling” success.

While Mexico and the US are economically integrating, so are Mexico and China. Politicians in Washington, most notably members of the Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, are now warning that Beijing is attempting to use Mexico as a “back door” to the American market as direct trade between the great competitors sharply declines.

In response to this trend, on December 7, the United States and Mexico agreed to cooperate in the monitoring of foreign investments “to guard against [those] that pose national security risks.” China goes unmentioned in the US Department of Treasury’s press release, but it isn’t that difficult to put two and two together.

In foreign direct investment alone, for instance, China spent three times more money in Mexico in 2021 than in 2019. Furthermore, in Nuevo León, the Mexican state with the highest total gross production, Chinese companies were responsible for 30 percent of foreign investment in 2021. “Nuevo León is having a geopolitical planetary alignment,” the state’s governor Samuel García declared from his palace in Monterrey two years ago. “We’re receiving lots of Asians that want to come to the US market.”

When he says Asians, he means in part companies like Japan’s Kawasaki, which in October announced that it would spend around $200 million to build a production plant in his state. Still, it is China who dominates. That same month, Lingong Machinery Group, a Chinese leader in the construction machinery industry, said that it would establish an industrial park in the state. The park will generate investments twenty-times larger than what Kawasaki put forward. Later in October, García went to Shanghai and announced other investments from Chinese firms, including those of Ningbo Tuopu Group and Shenzhen H&T Intelligent Control Co., which together amount around $1 billion.

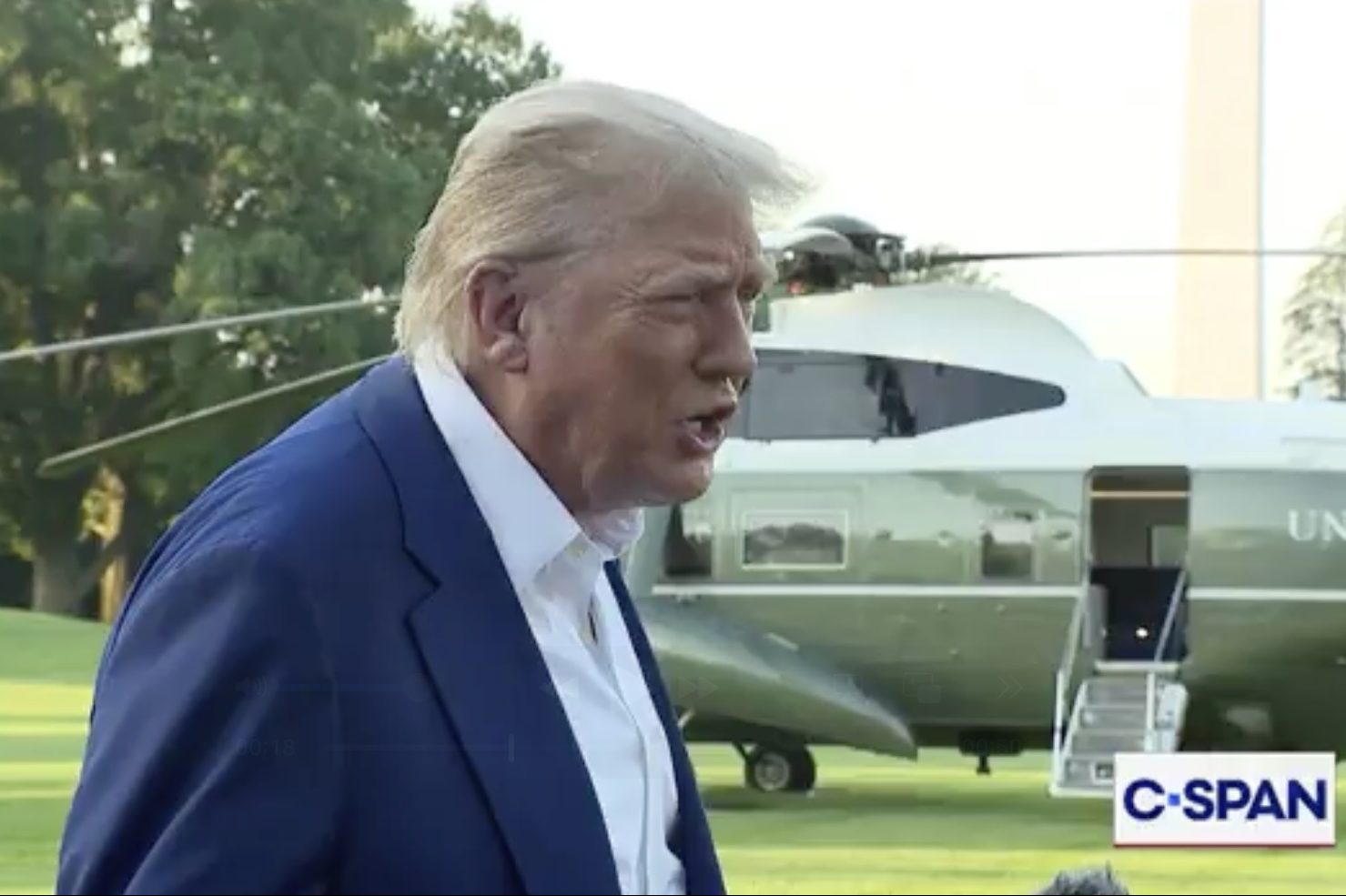

Treasury secretary Janet Yellen may say that the recent US-Mexico agreement “is not just China-focused” and instead based on “the general belief that it is important to make sure there are not national security concerns that are implicated in any foreign investments.” The truth is that after a devastating pandemic and Donald Trump’s trade war, China has taken advantage of an expansive North American trade deal. The broad-brush logic for their strategy sounds something like this: the US could restrict its trade with China but it won’t restrict its trade with Mexico.

For all of the talk about Mexico becoming the next global manufacturing hub and localization kicking globalization’s behind, a closer look reveals that US-Mexico integration hasn’t significantly changed the underlying dynamics between China and the US. The latest agreement and the fact that Mexico temporarily raised tariffs on countries it has no free-trade deals with in August, which includes China, evidences how the US is exerting diplomatic pressure. In a way, Mexico could be heading into something resembling a proxy trade war. Adding to the trend that discomforts the US, in November, two months after the tariffs were imposed, Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Chinese president Xi Jinping vowed to improve their trade relationship.

If Mexico becomes more of a manufacturing middle-man, the US will spend less time monitoring its direct trade with China and more time monitoring Chinese trade with its southern neighbor. This change in trade flows may harm China if Mexico chooses a path of continuing restriction, but evidenced by the US’s interest in monitoring Mexican trade, it also complicates things for the US. After all, Mexico’s commercial relationship with China is one that elevates their geopolitical relevance and generates them lots of money, so it is not exactly clear (absent from significant US push power), how Mexico would react if put in the middle of great power competition. For one, Mexico wants to both satisfy their largest economic partner and benefit from the immense investments pouring in from Beijing.

With Mexico being led by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and with his like-minded potential successor Claudia Sheinbaum leading in the polls, viewing US-Mexico integration as a decoupling success becomes even more difficult. AMLO has not been an easy partner to deal with for the US; he refused to attend the 2022 Summit of the Americas, where Biden announced his signature Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity. He did so objecting to the White House’s refusal to bring in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua. In 2023 he almost did the same with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco, initially citing his refusal to attend due to Peru’s inclusion in the meeting, with whom he had soured relations after expressing his opposition to the ouster of socialist Pedro Castillo.

AMLO and others in the MORENA Party ecosystem are not just difficult partners in general; they are especially difficult with the US. AMLO has slammed the US for spending billions to support Ukraine, and for the “genocidal” sanctioning of Venezuela and Cuba. Even more so, he defiantly told secretary of state Antony Blinken to mind his own business for the State Department’s criticism of Mexican electoral reform.

Meanwhile when it comes to China, you see little if any finger-wagging and absolutely no meeting-skipping from AMLO. To be fair, some of that is because China doesn’t condemn AMLO and instead fixates on its concrete commercial interests. Nonetheless, one cannot extract ideology when examining AMLO’s strengthening relationship with Xi Jinping. At his core, he opposes US hegemony.

The US-Mexico “bilateral working group on foreign investment review” has the potential to alleviate some of the US’s concerns. By tracking what Chinese firms are targeting in Mexico, the US believes that it will be better equipped to respond to potential threats. Nevertheless, the commercial and diplomatic relations between the three countries present an ongoing challenge. AMLO has no choice but to take the US’s wishes seriously, yet that doesn’t change the fact that he sees in China a partner that can help change trade dynamics in his favor.

Leave a Reply