China usually shuts down for the Lunar New Year, but Communist Party leaders have marked the arrival of the Year of the Rabbit with a burst of activity worthy of that skittish animal. They have followed their colossal flip-flop on zero Covid with a charm offensive to convince the outside world that China is open for business. In many ways it is as abrupt an about-turn as scrapping Covid controls in the first place.

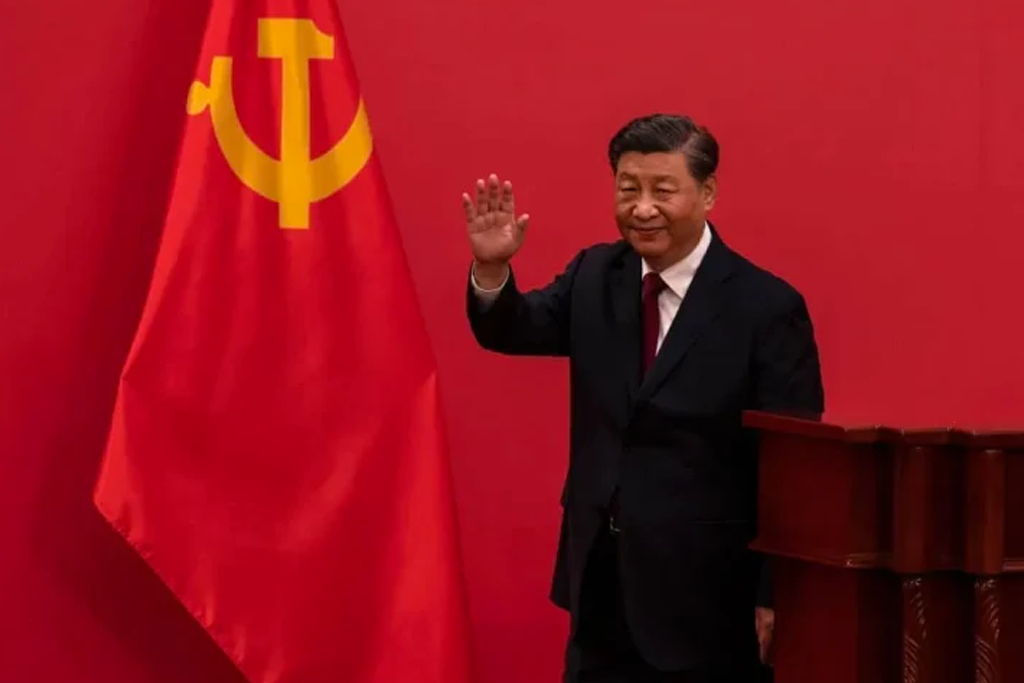

Xi Jinping despatched his trusted vice-premier and economic czar Liu He to Davos to schmooze with western business leaders. In his speech to the World Economic Forum two weeks ago, he mentioned “strengthening international cooperation” no less than eleven times. He said that the door for foreign investors would “open up further.”

At home, a heavy-handed crackdown on tech companies appears to be easing. The message is that “rectification” is over and soothing words have abruptly replacing threats. Gone too is Xi’s talk of “common prosperity” — code for greater state control, which has put a cloud over domestic business and foreign investment. Prime Minister Li Keqiang promised “deepening reforms to spur market vitality and public creativity,” according to Xinhua, the state news agency — the sort of market-friendly language that has become rare in Xi’s China.

It also seems that China wants its property bubble back. Restraints on heavily indebted real estate firms are also being lifted and money pumped into troubled developers. At the same time, Zhao Lijian, the most public face of China’s aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy has been shunted from his position as spokesperson at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to a backroom role handling border disputes. He had used the ministry lectern to spout xenophobia and peddle conspiracy theories, while trolling and growling his way around western social media.

Even those more hardened to Beijing’s opaque decision making are suffering from a form of whiplash, struggling to understand what it all means — and whether it is for real. “Are they open to business permanently or is this just some short-term effort to bounce back the economy?” asked Julian Fisher, vice-chair of the British Chamber of Commerce in China, during a briefing in UK parliament this week arranged by the backbench China Research Group. “How quickly will the door close again?” he added. The chamber’s most recent survey of sentiment among members — admittedly undertaken while zero Covid was still in place — was the most pessimistic ever; business people have been leaving China in droves, “jaded and embittered.”

China-watchers are also confused, with some questioning whether Xi is any longer in complete control. “Something has gone amiss,” one former senior US intelligence official told me. “Xi Jinping might have changed his mind, but he could well have had his mind changed for him.”

Just weeks ago, Xi appeared to be at the peak of his powers. He seemed to have eliminated all opposition and cemented an unprecedented third term as party boss. “Chinese history is full of sharp elbows and leaders are at their most vulnerable at the peak of their power,” says Anne Stevenson-Yang, founder of J Capital Research, who spent more than twenty-five years in China. She believes Xi is being quietly pushed aside. “All his significant policies have been reversed 180 degrees,” she says.

That may be wishful thinking, but Xi has certainly been damaged by the debacle of zero Covid and the country’s messy reopening with little obvious planning or preparation. Official propaganda is claiming the virus has peaked, that the country is over the worst and in any case China did better than everyone else.

But anecdotal evidence tells otherwise as Covid rips through more remote areas, aided by the mass migration for Lunar New Year. Officials say 2 billion journeys will be undertaken over the holiday period. Official Covid statistics are not credible, and independent modeling is uniformly dire. The British-based health data company Airfinity predicts, however, that up to 1.7 million people could die over coming weeks.

There may be a simpler explanation to the sudden talk of economic openness and reform — that is tactical and cynical. There is an element almost of desperation about it, an expression of just how dire the economic situation has become and the severity of the credibility crisis the party if facing. The economy has ground almost to a standstill. Partly this is a result of Covid restrictions, but also longer term issues ranging from the bursting of the property bubble (property accounting for up to a third of the economy) to geopolitical tensions and a shrinking population. Urban youth unemployment is running at almost 20 percent. Talk among foreign businesses is that China under Xi is becoming uninvestable.

There seems little doubt that reopening will provide a bounce to the economy. “But is it a dead-cat bounce?” asked Fisher. “It is becoming more uncertain because power is centralized more and more. I don’t think anybody can make any bets on the future of China,” he warned. “There are major concerns that ideology is trumping the economy.”

China’s leaders were also shaken by the intensity of last November’s protests, which no doubt played a part in the abandoning of zero Covid. Their worst fear will be of a population emboldened by the apparent success of that unrest. Protests have rumbled on through the new year celebrations: there has been mass defiance of a national firework ban and clashes in places where police tried to enforce it. The army of de-mobilized zero Covid enforcers has also been protesting against sudden layoffs and demanding back-pay they say they are owed.

Many of those who study recent Chinese history will tell you that it is punctuated by periods of relative openness and then closing. Reformers and liberals compete for influence with conservatives within the system, so the argument goes. There is some truth in that, but even during periods of relative openness the overriding prerogative has always been the survival of the Communist Party. That was what drove paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to launch reform and opening in the first place, and he was no liberal.

Perhaps the best way of interpreting the apparent new-found commitment to openness (if it is followed through — a big if) is that the party’s survival instinct has once again kicked in. It is desperate to get the economy moving again by all means necessary — and its future (and that of Xi) depends on its ability to do so.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.