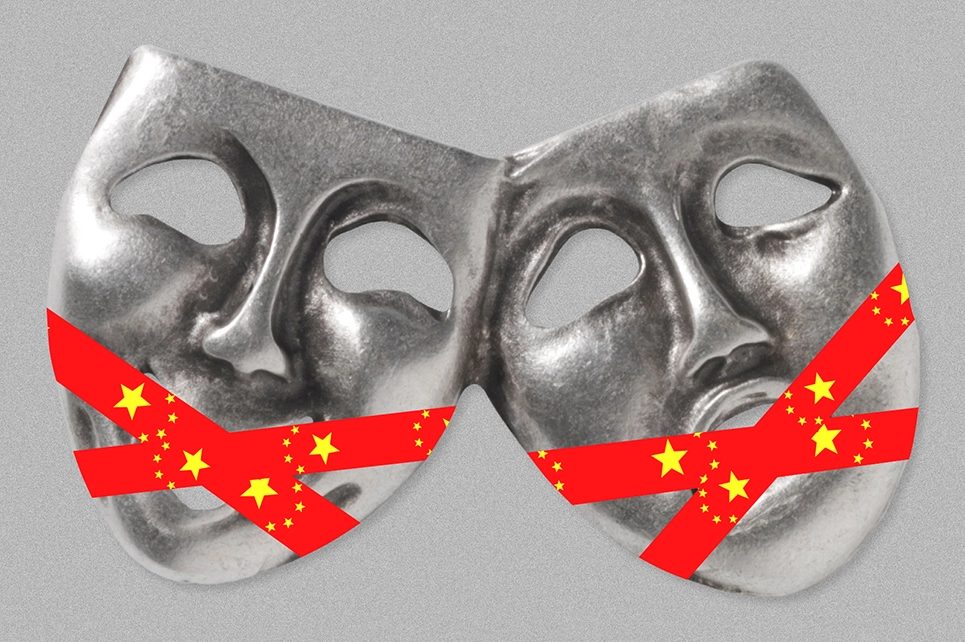

“The Chinese Communist Party is probably the funniest thing that exists,” the dissident artist Ai Weiwei once told me, “but it doesn’t have a sense of humor.”

Xi Jinping is exceptionally humorless, even by the standards of recent Chinese leaders

The brave band of comics in China’s fledgling stand-up comedy scene are discovering that poking fun at the grim-faced old men who run the country with an ever-tighter grip is a dangerous pursuit. Last month, at a comedy club in Beijing’s Dongcheng district, thirty-one-year-old Li Haoshi mocked a military slogan coined by President Xi Jinping. Li said that “Forge exemplary conduct! Fight to win!” reminded him of his two dogs chasing a squirrel. A clip of the show spread rapidly online. The Beijing Municipal Culture and Tourism Bureau said it would not allow Li to “wantonly slander the glorious image of the People’s Liberation Army” (PLA) and that his joke had a “vile societal impact.” Performances by Li, who goes by the stage name House, have been suspended indefinitely. His earnings have been seized and he is being investigated using a law that makes it illegal to “insult” the PLA.

State media then reported that a thirty-four-year-old woman had been detained for posting online support for Li, while a popular British-Malaysian stand-up comedian who goes by the name Uncle Roger had his Chinese social media accounts suspended for “violation of relevant law and regulations.” This has been followed in the past few days with the sudden shutdown of a swath of live shows and cultural events. These include a “What the Folkstival” concert near Beijing’s airport, where ten live acts were scheduled to play “acoustic music to soothe your soul”; a performance by a Japanese, Buddhism-influenced chorus group called Kissaquo; and a “Ladies Who Tech” convention. In each case, the perplexed organizers cited a variation of “unforeseen circumstances” or “force majeure” to indicate circumstances beyond their control — which is often used in China as a euphemism for higher powers. Privately, performers linked the cancellations to Li Haoshi’s joke.

In many ways it is surprising that China has a stand-up comedy scene at all. The CCP is not known for its tolerance of dissent. During my time as a correspondent in Beijing, I met a young comic who had recently returned from studying in New York and was determined to bring a brand of irreverent humor to China. He quickly became disillusioned.

Nevertheless, in the past few years comics have managed to carve out a lively stand-up scene. It originated in small cafés and bars in Shanghai and Beijing, but has spread. By one estimate, the number of comedy clubs in the country has risen from single figures in 2018 to nearly 180 in 2021, with around 1,500 full-time comedians. On paper, at least, their material is tightly constrained. Clubs and performers are required to obtain licenses and their scripts must be approved in advance. Rules require them to promote “social morality” and to “love the motherland and support the CCP’s line and policies.” That said, comics frequently veer from the script, and have been adept at using irony, metaphor and surreal humor to push the boundaries.

Comedians have had run-ins with the authorities before. Several have been criticized for “inappropriate” or “vulgar” jokes. A female stand-up comedian called Yang Li, also known as the “punchline queen,” faced sanctions after being accused of insulting men during one of her shows. Li Haoshi was on particularly dangerous ground because he was ridiculing Xi’s own words, and the criminalization of his joke is the most serious setback yet for China’s stand-up scene. It might even prove terminal.

Xiaoguo Culture Media, the company that turned Li into a star and pioneered stand-up comedy in China, has also been targeted with heavy fines and a suspension of all performances. It produced a successful show called Rock and Roast, a stand-up comedy competition which typically poked fun at daily life in China. The show attracted a huge following, particularly among the young, during the pandemic when lockdowns confined many people to their homes.

Xi is exceptionally humorless, even by the standards of recent Chinese leaders. Like Mao Zedong before him, he believes that art is an instrument of politics, and that entertainers should be role models spouting bland CCP homilies. Or, as the Beijing authorities put it when they banned Li Haoshi, artists and writers should have “correct creative thinking” and “provide healthy spiritual nourishment for the people.” Li was also targeted by an army of online nationalists, who are given considerable leeway on China’s otherwise tightly controlled internet.

The crackdown on humor should also be seen in the light of Xi’s broader and intensifying indoctrination drive, launched in the wake of his “zero-Covid” debacle. This has included mass-study campaigns to spread “Xi Jinping thought” throughout society. The CCP must “unify its thinking, unify its will and unify its actions,” according to Xi.

Li is learning the hard way that the CCP won’t stand for humor and ridicule. Perhaps he became overconfident, and perhaps, too, he should have seen it coming. His career is almost certainly over, and he could face years in prison. ‘I will take responsibility for this, stop all performances, reflect deeply,” he said on his social media account. Which is itself horrible jargon and may also be a joke. We’ll never know, but the party is taking no chances: that was the last thing he posted before he was banned from any further online comment.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.