History repeats itself — but sometimes in reverse. Only a pessimist would have predicted a global pandemic followed by a growing regional conflict. And yet the ongoing fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan — and its accompanying web of political ambition, ethnic tensions and territorial disputes — leads to uncomfortable comparisons with the start of World War One.

That conflict began after Austria threatened Serbia, resulting in Russia’s pledge to protect its fellow Slavs against outside aggression. Germany assured the world, and Russia, that it would not tolerate hostility towards Austria. France informed Germany that it would come to Russia’s defense if it came under attack. Britain was something of a wild card, promising only to protect Belgian neutrality in the event of a conflict, as well as warning against those who considered waging war in British waters.

In this 2020 reboot, the Balkans have been swapped for the Caucasus, and the principal players have been recast. The dispute this time is between Azerbaijan and Armenia, over a territory internationally recognized as belonging to the former but populated by people from the latter. Politically, Azerbaijan is heavily backed by Turkey (the two describe themselves as being ‘one nation, two states’), and Turkish President Erdogan has stated his country will help Azerbaijan in ‘every way’. Turkey is the only nation among the international community not to call for an immediate ceasefire.

Armenia, meanwhile, has traditionally enjoyed support from Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union. But the Kremlin now has frostier relations with the current Armenian government compared to its predecessors, meaning that Russia has been less bellicose than Turkey by calling for a cessation of hostilities. However, it has indicated it will not tolerate attacks on Armenian soil — and already some of the fighting (mostly exchanges of artillery fire) has erupted outside of the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia is also a member of Russia’s Collective Security Treaty Organization, a Muscovite answer to Nato, and its tensions with Turkey date back to the slaughter of the Armenian genocide, a blueprint catastrophe for the Holocaust in which over one million Armenians were killed.

Moscow is keen to maintain its newfound friendship with Ankara, a bond formed over Putin and Erdogan’s growing anti-Western sentiment. But the replacement of the incumbent Armenian government would likely not upset the Kremlin. Putin is walking a fine line: balancing the desire to see an ally come crawling back without the risk of utter defeat. If Russia declines to help Armenia, it will lose the support of any subsequent Armenian government. Therefore, if attacks against Armenia become severe enough, Moscow will intervene — the Kremlin has a standing force of 3,000 troops on a base of its own in Armenia.

Should Russia become embroiled in an Armenian conflict, it will need to reinforce and resupply its current troops in the country. To do this, it will need to establish a land connection — and this can only run through neutral Georgia.

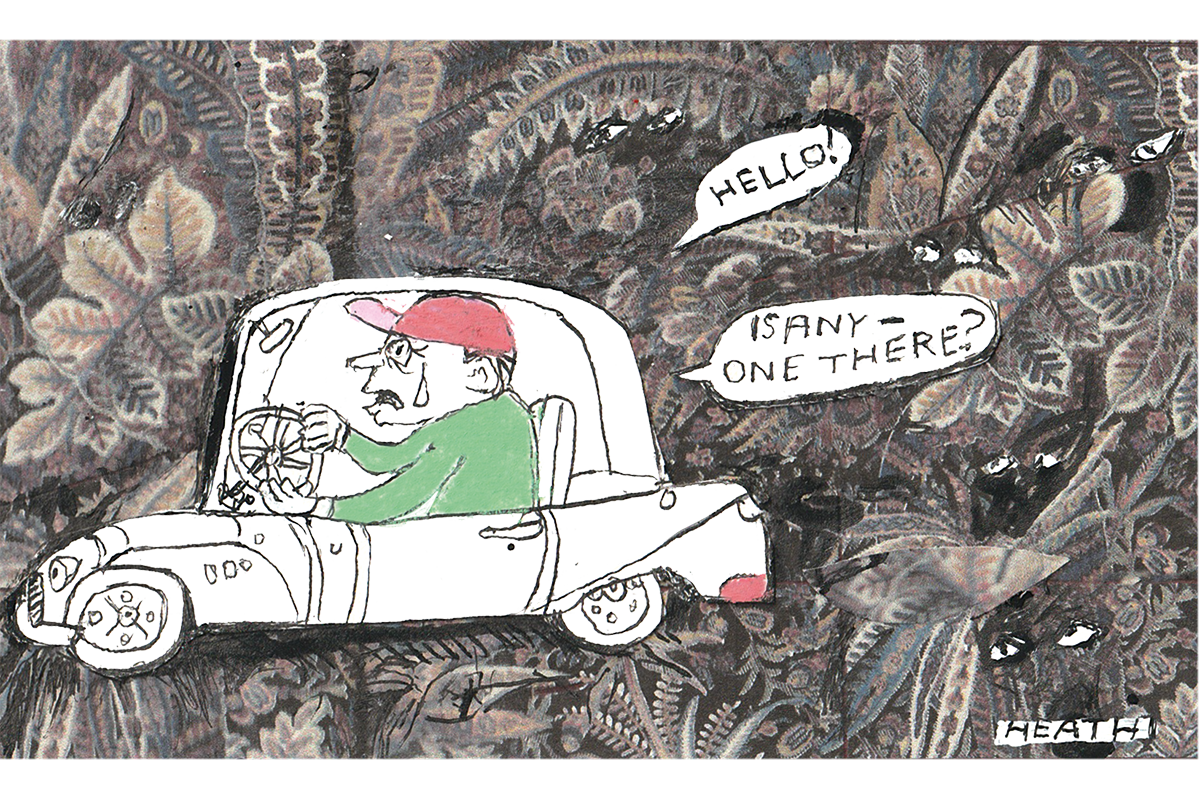

Georgia is, arguably, in the worst possible position of all. Continuing the World War one analogy, Georgia plays the part of Belgium — only unlike Belgium, Georgia does not have the power of the British Empire behind it guaranteeing its independence.

Georgia is also at considerable odds with Russia. The country has two Russian-backed separatist states of its own (where Russia keeps yet more troops) and whose secession was one of the main reasons behind the Russo-Georgian war of 2008. Although Russian troops withdrew from Georgia proper, the two have been diplomatic opponents ever since: the West’s muted response to the conflict only buoyed Russian hopes of getting away with its subsequent military intervention in Ukraine in 2014.

Georgia is also home to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, the only supply of natural gas in the region that does not come from either Russia or Iran. Partly as a result of this, Georgia has been firmly aligned with the West since 2003, contributing troops to Nato operations in Iraq and Afghanistan while enjoying substantial American and European investment in almost all sectors. The pipeline has also pushed Georgia towards Azerbaijan and Turkey, who respectively control the opening and terminus of the pipeline.

The spillage of war into a greater regional conflict does not solely depend on possible Russian involvement. Iran has recently dispatched troops and armored units to the Armenian border in a show of support for Armenia, despite sharing religious, cultural and partial ethnic ties with Azerbaijan, it has backed the Armenians in their claims over Nagorno-Karabakh. Positive Azerbaijani relations with Israel have been a contributing factor, as well as tensions between Turkey and Iran. Although Tehran has offered to mediate peace talks, the proposal has been rejected — it is too publicly favorable towards the Armenian side.

[special_offer]

As in World War One, it will not take much for the conflict to really heat up. For example, if Azerbaijan decides to take out Armenian artillery positions in the north by sending in troops or armored units, Russia could be forced to respond. It could then drag in Georgia by forcing a land connection between its own borders and Armenia. Another route could be if Armenia suddenly wins a series of victories and Azerbaijan is forced to retreat — Ankara would not want its ally to lose, as Turkey, too, would lose international face. This would also be the second embarrassment endured by Turkey in almost as many months after its climbdown against the Greeks in August.

With the West focused on COVID-19 and America embroiled in the run-up to its election, the Caucuses have avoided international attention. Only France is making an effort to broker peace talks. But with President Macron’s rhetoric being seen by Baku as pro-Armenian, his efforts are likely to be fruitless.

There are many ‘ifs’ and ‘maybes’ before the outbreak of a regional war, but the same was true of 1914, and again in 1939. Given the year we’ve so far had, perhaps the pessimist will be proved right.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.