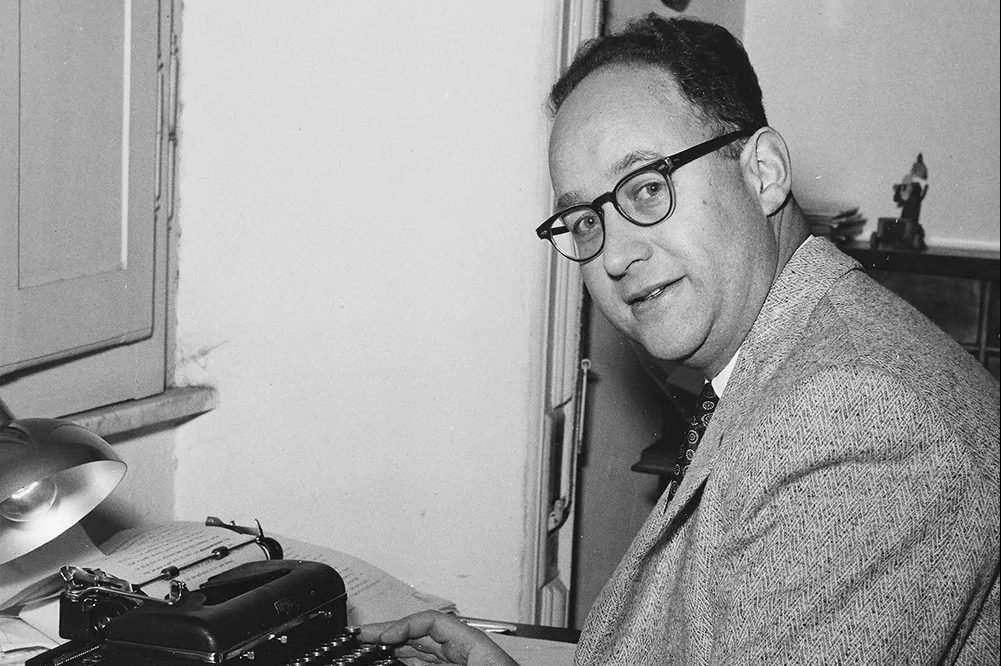

There’s a specter floating inside the head of a certain type of young woman. It’s the fast-talking, sex-realist American academic Camille Paglia. She was big in the 1990s but my parents haven’t heard of her. “Did she write Fear of Flying?” asks my dad. On sections of the internet she has become a folk hero. She’s an ideological guiding force for the female hosts of Red Scare, an influential left-ish podcast which was described by the Cut as “a critique of feminism, and capitalism, from deep inside the culture they’ve spawned.” Paglia is equally popular among some conservative factions: a 2017 debate between Paglia and Jordan Peterson has amassed 3.5 million YouTube views. Her TV appearances from the 1990s are passed around online like prison contraband: she disses Susan Sontag (“She’s dull, she’s boring, she’s solipsistic”), and denounces, before her time, “any politicized agenda in the classroom.”

Paglia gives us proof that you can make a sophisticated, original point without resorting to academic Esperanto

I first read Paglia’s breakout book, the 712-page Sexual Personae, when I was nineteen and studying online during the Covid lockdowns. At that point I knew my academic career was over because of my semi-religious enthusiasm for Hollywood’s classical period. My lecturers were intent on decolonizing and deconstructing, but their attempts were doomed in the face of prophetic screenwriting and of soft focus, which I’d started to think of privately as magic. Here only Paglia seemed to understand me. Greta Garbo was an interwar stand-in for the mythological Artemis, and Elizabeth Taylor, the writer’s childhood obsession, a fanged, sniping Venus. All roads, according to Paglia’s most celebrated theory, led back to the mystery cults of the ancient Mediterranean. The monotheistic religions once had a shot at quashing this pagan continuity, but were doomed to live with it whenever it re-emerged in modern culture, which it often did. Modern progressives were hopeless against paganism’s violent impulses and sexual imperatives — the sort you’d expect at the Roman Bacchanalia. Its archetypes, gods, goddesses, and vampires, could be found in all western art and literature.

This sounds like material for Pseuds Corner — but few scholarly books are as readable as the 1990 Sexual Personae, and none are as funny. Paglia later led me to wits like Mary McCarthy and Gore Vidal, but at the time her writing style seemed totally unique. “She showed me the value of writing and speaking in a confident, direct, declarative manner, without mealymouthed qualifications and apologies and alienating academic jargon,” says Jack Mason, who credits his underground podcast The Perfume Nationalist for some of Paglia’s renewed fame.

If you want to know the kind of academic jargon Paglia is pitted against, look to someone like Judith Butler, the revered poststructuralist, who holds the contemporary humanities under a suspiciously drowsy spell. This is someone who once won the first prize in a Bad Writing Contest for a ninety-four-word sentence about hegemony, Althusser, and “structural totalities.” In a 1999 foreword to her classic text Gender Trouble, Butler defends herself for sentences that “call into question the subject-verb requirements of propositional sense:” they’re the best vehicle for her “radical views.” (Tell that to Mao, whose Quotations were recorded for the benefit of provincial farmers). Paglia learnt to write by keeping a notebook of Wilde epigrams. By contrast, every paper I read for university seemed to have been written by someone who’d spent hours in a candlelit cell, tracing out Butler’s verbal calisthenics with quill and ink.

On my university course there’s a new compulsory module called “East Asian Imperialisms.” This ideological coup is made only worse by its linguistic ammunition: you can’t even mention the name of the class without inadvertently agreeing with the lecturer. (“Yes — I believe you — there are several different kinds of East Asian imperialism,” I imagine myself gasping out to Butler et al, who brandish large plural morphemes as they chase me through the night). At Durham, there’s “Geographies of Difference,” at Surrey, “Histories of Sex/uality,” at Exeter, “Queer Ecologies.” (“How,” asks the website, “can attention to queer theory help to challenge the colonial rationalist binaries including the un/natural, non/human, dis/order, dis/orientation, un/civilized and un/known in this moment of planetary precarity?”).

I hate this cryptolect not only because it is unreadable (I get the same nauseous feeling from Butler et al as I do from the fake-compassionate ad copy on a smoothie, or from generative AI) but also because it exists, in permanent condescension, to demarcate the right-thinkers from the wrong-thinkers. Despite its facade of concern for the “disenfranchised” and “subaltern,” it works to separate those who can afford university from those who cannot. If you can’t keep up with its bylaws and vagaries, you’re out. To the academy, everything is exclusionary — apart from its shibboleths.

Paglia gives us proof that you can make a sophisticated, original point without resorting to academic Esperanto. In its search for pagan archetypes, Sexual Personae spans centuries of apparently continuous art and literature, from the Aeneid (a “closet drama”) to Emily Dickinson (an “autoerotic sadist”). The wit may date back to a McCarthyan midcentury, but the book’s breadth is unmistakably a hangover from the New Age upheaval of the late 1960s, which the author experienced first-hand as a young woman. “Today’s academic leftists are… timorous nerds who missed the Sixties while they were grade-grubbing in the library,” she says in her essay Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders. Her work is as defiantly multicultural as George Harrison playing the sitar, and is littered with telltale preoccupations of psychedelia, like Aubrey Beardsley and the ancient cults of Dionysus.

This signature Sixties-ness may be a clue to her resurgence. My generation occupies what often seems to be the exact inverse of the Summer of Love. We are theoretically connected to people all over the world, but secluded — through both algorithms and the narrow language-games of academia — from any New Age-y width of thought or belief. When you spend lots of time immobile on the internet, you’re shut off from an awareness of your own body — it’s not uncommon to see young people calling themselves “brains in meat suits,” or occupants of a “flesh prison.” We are having less sex than those before us, and we cover our eyes when there’s nudity on TV. All of this might explain a collective aversion to the Boomers, who were born between 1946 and 1964 and got to stomp around happily in the hallucinogenic debris of the Sexual Revolution. But it also explains why ideas like Paglia’s feel, to us, as potent as psychedelic drugs.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply