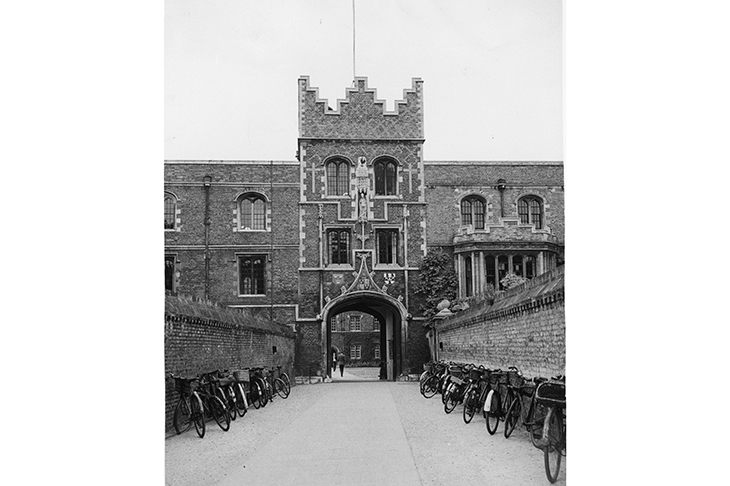

Last month, writing elsewhere, I quoted the website of the China Centre at Jesus College, Cambridge: ‘Under the leadership of the Communist party of China since 1978, [China] has experienced an extraordinary transformation…China’s national rejuvenation is returning the country to the position within the global political economy that it occupied before the 19th century.’ The tone sounded propagandist not academic. This month, all mention of the Chinese Communist party disappeared from the China Centre home page. Now the Centre says it concentrates on ‘mutual understanding between China and the West’, contributing to ‘harmonious global governance’, which should be ‘non-ideological and pragmatic’. We must meet ‘global challenges’ together, says Jesus (the college, not the religious leader), such as ‘health pandemics, species extinction, global warming, inequality of income and wealth’ etc. A particular health pandemic has made the former propaganda too blatant.

Further investigation of Jesus’s China Centre site suggests all is not well. Its section called ‘External engagement’ records nothing since October, when Prof Peter Nolan, the center’s director, met Mr Ren Hongbin, the vice-chairman of China’s State-owned Assets and Administration Commission. Prof Nolan is a seasoned China apologist. His latest book ‘explores China’s rich history of regulating the market in the interests of the mass of the population’, says its blurb. ‘For over 2,000 years the Chinese bureaucracy has sought pragmatically to find a way in which to integrate the “invisible hand” of market forces with the “visible hand” of ethically guided government regulation.’ In March last year, Prof Nolan spoke in Beijing on China’s Peaceful Development and Modernization of National Defense.

I find no mention on the China Centre website about how, this February, Jesus College was accused of ‘reputation laundering’. Its China/UK Global Issues Dialogue Centre (which works in partnership with Tsingua University, Beijing) produced a study on global governance reforms in communications and technology. It was paid for by Huawei, the Chinese communications and technology company. In his foreword to the Dialogue Centre’s study, the vice-chancellor, Stephen Toope, says he wants China to be big in ‘multilateral governance solutions’. The study praises Huawei: ‘All intellectual property associated with 5G has been made freely available by the CEO of Huawei.’

Jesus College has announced it is stopping all direct investment in fossil fuels. I notice, however, that in February its China Centre hosted a supportive lecture about the China Pakistan Economic Corridor which is ‘by far the largest of China’s Belt and Road projects’ and involves ‘construction of coal-fired power stations and coal mines’. Profs Nolan and Toope have spoken in favor of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Last year, the then Master of Jesus, Prof Ian White, went off to be vice-chancellor of Bath University. Bath has a Centre for Research in Education in China and ‘strategic partnerships’ with two Chinese universities, Tsinghua (see above) and Zhejiang. Zhejiang’s website presents its section on the leadership of its own university in two columns, one for the senior academic staff, the other for the Secretary of the Communist Committee of the university and his Vice-Secretaries. As I understand it, all universities in China, including the Chinese campuses of British universities, have party secretaries on the staff. How does Bath, or any British university, reconcile such governance with academic freedom?

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

There are universities with China partnerships throughout Britain. Nottingham has a campus in Ningbo, Liverpool in Suzhou. Nottingham’s School of Contemporary Chinese Studies had to close in 2016. This followed attempts by the Chinese embassy to ‘no-platform’ speakers it disapproved of and persuade academics not to speak publicly about China. Oxford pulled out of Huawei funding early last year, but 17 British universities are reported still to have Huawei deals. These include Surrey University’s $7.5 million 5G Innovation Centre and projects in Edinburgh, Southampton, Cardiff, Manchester (whose sister city is Wuhan), York and even the Royal College of Art. Imperial, home of Prof Neil Ferguson and his famous model, is, in its own words, ‘the UK’s number one collaborator with Chinese research institutions’. There is a ghoulish fascination in looking up Imperial’s presentation of itself when Xi Jinping visited the premises in 2015. ‘President Alice Gast with President Xi Jinping’, its website headlined the photograph. There followed pictures of Prince Andrew introducing George Osborne to Xi in Imperial’s reception area, and Madame Xi being presented with ‘a special cape that used big data analytics to create the ideal design, color and fit for the First Lady’. This resembles Melmotte’s banquet for the Emperor of China in The Way We Live Now.

In his foreword to Jesus’s Huawei-funded study, Prof Toope likens Cambridge’s work with China today to ‘the pioneering work of Joseph Needham’, its great historian of Chinese science. I am reading Hugh Trevor-Roper’s The China Journals, recently published. These record, amusingly, his visit to Mao’s China in 1965 and his discovery that the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding (SACU), under whose auspices he was traveling, was a Chinese Communist party front organization, including in its funding. Trevor-Roper exposed this. When he did so, the chairman of SACU, Joseph Needham, had him thrown out. In those days, the sums of Chinese money were tiny — the SACU annual budget was £9,000 ($11,000). Today, they are huge. The universities crave the money, the access, the students, the power. All these things have turned their heads.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.