Johnston’s Gate isn’t the only entrance to Harvard Yard. For years, money, status and secret lists have opened back doors into Harvard University for a select group of privileged students. And the easiest way to open these doors? The right parents.

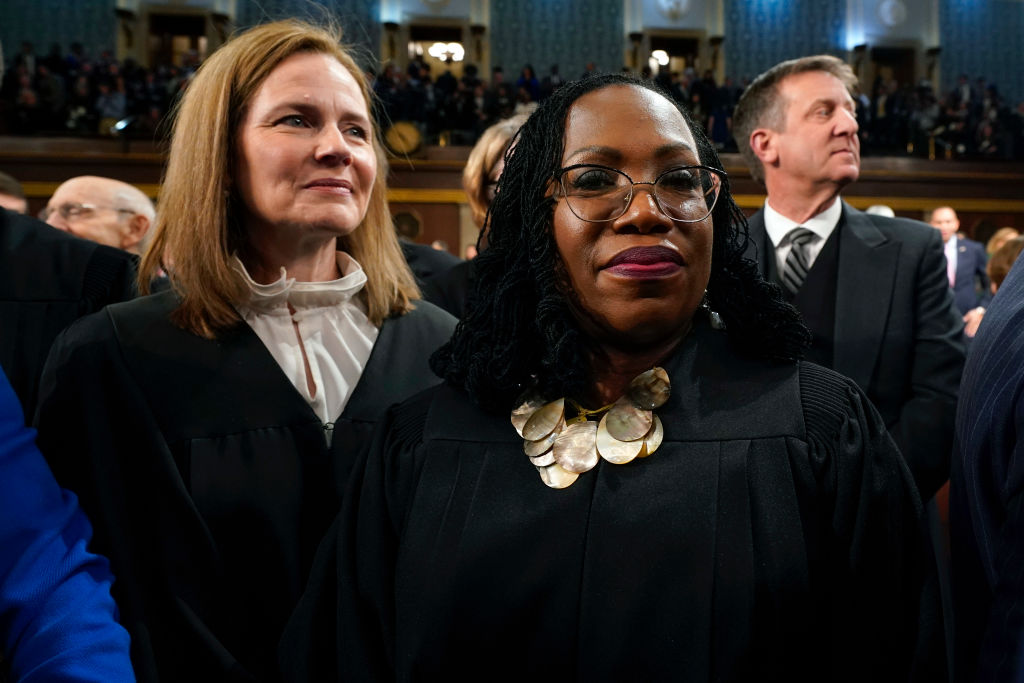

According to the Harvard Crimson, over a third of the class of 2022 had a parent or other relative who attended Harvard. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action, the admission policy that has created America’s aristocrats is starting to take some heat. Could legacy admission be the next to go? Three Boston-based advocacy groups say yes.

On Monday, Lawyers for Civil Rights filed a thirty-one-page complaint against Harvard University on behalf of their plaintiffs: the Chica Project, the African Community Economic Development of New England and the Greater Boston Latino Network. The document claims that legacy admissions favors white students and violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“Title VI says that any recipient of federal funds is prohibited from discrimination on the basis of race and that’s the basis of the complaint that we filed this week” Oren Sellstrom, an attorney working on the case, told The Spectator.

Sellstrom did not say whether the plaintiffs approached Lawyers for Civil Rights before the Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action was announced, but did explain that the case “heightened the urgency of moving forward to root out unfair and unmerited preferences.” The complaint quotes the Supreme Court’s ruling multiple times.

“It’s relevant because the court put a premium on examining individual students’ merit. Donor and legacy preferences are anything but merit based,” said Sellstrom. “Your family’s last name, or the size of your family’s bank account, has nothing to do with individual merit — and that is the core of our complaint.”

Harvard declined to comment on the lawsuit but said they would maintain their commitment to diversity following last week’s ruling. “As we said, in the weeks and months ahead, the University will determine how to preserve our essential values, consistent with the Court’s new precedent,” said Nicole Rura, a Harvard University spokesperson.

The lawsuit calls on the Department of Education to launch a federal investigation under Title VI into the university’s preference for legacy students, but this isn’t the first time Harvard has come under fire for elitist admission policies. Nor is the lawsuit representative of Harvard’s real issue. Banning legacy admission may increase campus diversity slightly, but Harvard doesn’t have a race problem so much as a nepotism problem.

In 2018, John M. Hughes, a lawyer for Students for Fair Admission, released several emails from Harvard’s dean of admissions and financial aid William R. Fitzsimmons. The correspondence said the quiet part out loud: Harvard prefers rich kids.

In one 2013 email headlined “My Hero,” a former dean thanked Fitzsimmons for admitting students connected with a donor. “Once again you have done wonders. I am simply thrilled about the folks you were able to admit. [Redacted] and [redacted] are all big wins. [Redacted] has already committed to a building,” the email said. In a separate email, an administrator wrote of a hopeful applicant whose family owned “an art collection which conceivably could come our way.”

Documents from the trial also revealed that Harvard compiles a dean’s interest list every admission cycle to keep an eye on “high priority” applicants. According to the Crimson, students on the list are often related to top donors and are mostly white and wealthy.

No one outside of the administration knew about the dean’s interest list or the similar director’s list — a group of select applications compiled by the director of admissions — until the SFFA lawsuit. But that hasn’t stopped the secret admissions practice from shaping Harvard’s student body for years. According to the Crimson, more than 10 percent of the Class of 2019 were on the two lists. Between 2010 and 2015, students placed on either list had a 42 percent chance of getting into Harvard, more than ten times the current acceptance rate.

SFFA’s filing referenced another little-known list called the “Z-List” — a “side door” to the elite university. Students on the list, who are often legacies, are guaranteed admittance but are asked to take a gap year before enrolling.

Peter Arcidiacono, a Duke professor of economics, used the data Harvard released during the SFFA lawsuit to reveal the university’s staggering preference for legacy students. His research found that a typical white applicant with a 10 percent chance of admission would see his odds rocket five-fold if he were a legacy and seven-fold if he were on the dean’s interest list. The data also accounts for advantages children of faculty have.

And it’s not just white students who benefit. Across every racial demographic, LDCs (legacy, Dean’s interest list or children of faculty) all enjoy higher admission rates. In fact, admission rates for Asian and Hispanic LDCs are 34 and 37 percent respectively, compared to 33 percent for whites. African-American LDCs have the lowest admission rate at 27 percent. On average, LDC admits also have slightly weaker applications than the typical admit. Harvard’s claim to meritocracy and their 4 percent admission rate is a myth. Once your family has reached the privileged legacy status, your race doesn’t matter. It might help you or hinder you in comparison to your other legacy competition, but not significantly. America’s “normal” students are the ones being hurt.

Although legacy applicants are nearly 70 percent white, Arcidiacono does not think abolishing legacy preferences would have a significant impact on campus diversity now that affirmative action has been banned. “Racial preference is more important than legacy in creating diversity,” he told The Spectator. “Ending legacy admissions does make some impact but it doesn’t come close to balancing it off by itself.”

Still, Sellstrom said Title VI pertains to legacy admissions since the law encompasses unintentional discrimination that impacts communities of color.

“We do not necessarily believe that banning legacy and donor preferences is going to fully make up for the loss of traditional affirmative action, but it is a significant step that needs to be taken in order to root out what is essentially affirmative action for white students,” Sellstrom said.

The bad news for Harvard is that Americans don’t need to agree why they dislike legacy admissions — most still find it unfair. Both Justices Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor argued against legacy admissions in opposing opinions from the affirmative action decision. Another problem for elite colleges is that some of the harshest critics have come from within their own classrooms. In 2014, Brown University freshman Viet Andy Nguyen founded EdMobilizer, a network of first-generation college students opposed to legacy preference as well as other admissions practices. Students for Education Equity, another Brown group which works with students from across elite universities including Harvard, was formed more recently to tackle similar issues.

“As far as I am aware, the consensus among the Ivies is that legacy consideration should be eliminated,” said Nick Lee, the group’s co-lead for admissions and access. “With the Supreme Court case, it feels contradictory and the overwhelming response I’ve received is that legacy must be the next to go — it’s been resounding. This has been something that has only doubled down now that affirmative action has ended.”

In 2018, Brown’s student government passed a referendum calling for legacy consideration to be abolished. According to Niyanta Nepal, SEE’s co-president, it was passed after a member of Brown’s administration met with the student government to defend legacy preferences as a way to maintain racial diversity.

“Leaning on legacy to make sure we’re meeting those demographic marks seems like a problem to me,” Nepal told The Spectator. “Most people I talk to don’t want to think the only reason they got into this university is because their parents got in — they want to think they deserved it. And I think that they did. They are qualified to be here. I just don’t think they should be given an upper hand for who their parent is.”

Still, it isn’t likely that many elite colleges are going to end the practice unless compelled to do so by law. Wealthy legacy students “take the guesswork out of admissions,” said University of Colorado economist Ethan Poskanzer. In 2022, Poskanzer co-authored a study using sixteen years of admissions data at an elite Northeastern college. Unsurprisingly, the study found that legacies are more likely to matriculate than non-legacies and more likely than their peers to donate after graduation. Another blessing — they don’t require financial aid.

Brown’s administration had been reluctant to get rid of legacy consideration, according to Nepal, although they have been receptive to SEE’s other initiatives. Once the fall semester begins, Nepal expects to see rallies across the Ivies. “We haven’t fought that hard against them because up until this point we have been trying to find more middle ground solutions. From this semester onwards, it will be a real fight.”