Is the Loch Ness Monster real? Many thousands of people think so. “Existence ‘plausible’ after plesiosaur discovery,” the BBC reported. “Hundreds join huge search for Loch Ness Monster.” Not only that. The Beeb had live coverage of congressional hearings about possible UFO sightings in July. It ran a series on the yeti the previous month asking: “Is something out there in the Himalayas?” Last year, an Autumnwatch presenter took seriously the possibility that large cats are roaming the countryside.

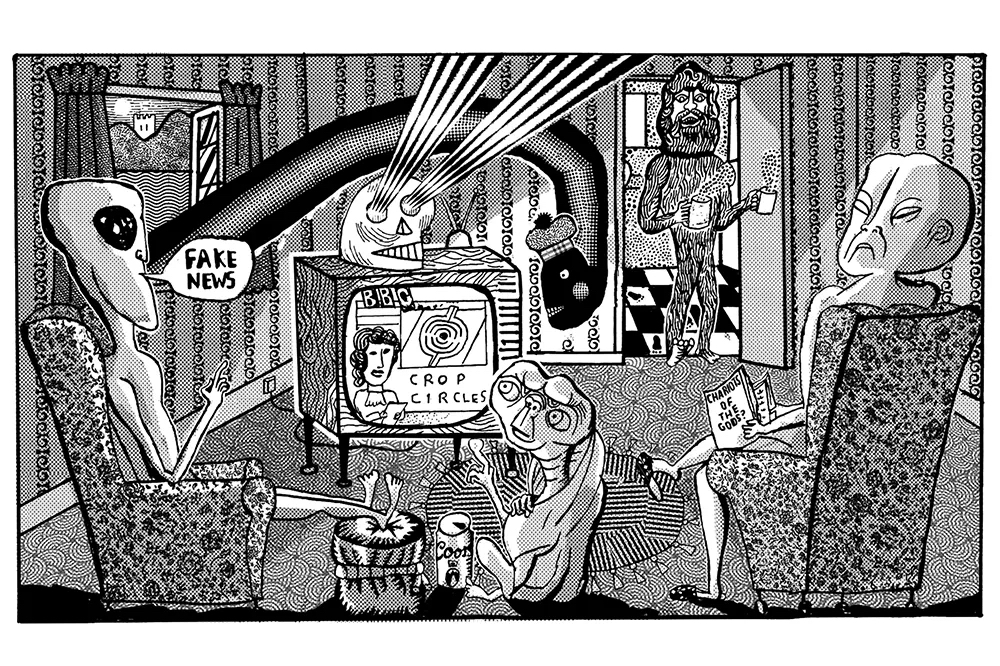

What’s coming back next? Poltergeists, Ouija boards, the Bermuda Triangle, crop circles?

Have we been time-ported back to the 1970s? I know clickbait journalism these days requires you to set your gullibility rating to max, but these old, tired clichés of pseudoscience are scraping the barrel. What’s coming back next? Poltergeists, Ouija boards, extrasensory perception, reincarnation, the Bermuda Triangle, crop circles? Each generation has to learn that the world is very, very thinly populated with ghosts, aliens and undiscovered megafauna but very thickly populated with charlatans.

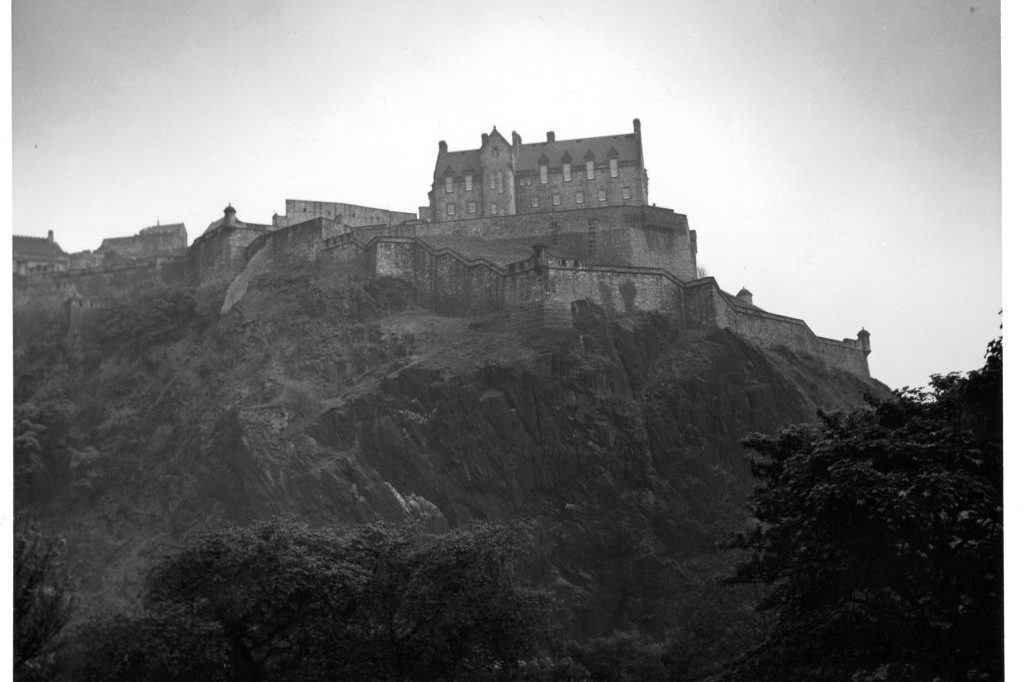

There’s nothing to support any of these mythical beasts except a few grainy and dodgy photographs. Literally the only picture of a putative plesiosaur in Loch Ness was taken in 1934. It shows something that could be anything from six inches to six feet long but was anyway exposed as a hoax decades ago.

What happened to common sense, or simple probability for that matter? The notion that a massive reptile could escape unfilmed in a Scottish lake, or a massive ape on Himalayan glaciers, or flying saucers in the sky, is for the birds and always has been. These fantasies grew steadily less plausible with the sale of every iPhone.

But the case for most of these creatures existing was always ecologically nonsensical anyway. If a thirty-foot plesiosaur lives in Loch Ness, what exactly is it feeding on? This is an “oligotrophic” stretch of water, meaning its acidic waters lack the nutrients to support more than a very meager food chain. Trout in the lake rarely get bigger than a pound. Salmon come in from the ocean but only for a few months of the year. The plesiosaur would eat all the fish in the loch in a few weeks. Well, maybe it’s a herbivore? Nope: there’s barely any weed in such a deep, low-nutrient loch even in summer, and what there is shows no sign of being grazed (surreptitiously?) by a massive herbivore.

But one plesiosaur would not be enough: you need a minimum viable population. Anything less than 100 or so would be far too inbred to survive. And how did they get through the last Ice Age when the loch was frozen solid? None of this deterred the BBC from writing that ridiculous headline on its children’s CBBC page in June: “Existence ‘plausible’ after plesiosaur discovery.” The discovery in question was that some plesiosaurs once lived in (very different and ecologically rich) freshwater environments but — er — around 100 million years ago in what is now the Sahara. The only argument left for taking Nessie seriously is that she has gained the sacred status of Santa Claus and it’s a shame to poop the party.

The same arguments apply to the yeti. If it lives on Himalayan glaciers, it won’t find any food. If on alpine meadows, it would have to eat yaks, which might get it noticed by yak herders. If in the forests below that, how come we have identified pretty well every butterfly, shrew and plant in the region but have missed an eight-foot ape? Yet the BBC this year finds “Seven reasons why the yeti might actually exist.”

I devoured this stuff when I was about ten, feasting on monster mysteries, but then I grew up

Interstellar aliens may one day show up on Earth: it is highly likely they exist somewhere in the universe. But the idea that alien spacecraft can flit through our atmosphere for decades without one decent photograph being taken was silly enough when Box Brownies were few and far between, but today, when everybody has a camera on their phone and the skies are full of pilots, it grows ever more bonkers. After all, a tiny, nondescript greenish bird called a Tennessee warbler cannot turn up on the Hebridean isle of Barra — as it did last month — without being spotted. Yet somehow we are all missing flocks of flying saucers?

Nasa recently announced an independent report into a catalogue of unexplained sightings, such as of objects making sharp turns at high speed, or plunging into and out of the ocean, as glimpsed by fighter pilots and others. It followed up by appointing a director of Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena research, which led a lot of people to celebrate that an official endorsement of UFOs had at last arrived. In fact, it shows that Nasa loves anything that gets it in the news and grows its budget.

The vast majority of UFO sightings can be explained by balloons, aircraft, drones or smudges on windscreens. The early ones, in the 1950s, probably included high-altitude, high-speed Blackbird spy planes, which were a closely guarded secret at the time. Perhaps some secret military drones today are capable of seemingly impossible feats. But the fact that 5 percent or so of sightings cannot be explained does not constitute evidence of visiting aliens: it constitutes evidence of things that are too blurred to explain. Evidence for aliens would be high-quality footage of aliens.

The Mexican Congress plumbed new depths of gullibility this year when it displayed a couple of supposedly alien corpses that were long ago debunked as fakes. The Telegraph’s Sarah Knapton, showing commendable common sense, pointed out that the bodies were made of a “hodgepodge of human and animal bones,” one having a femur where its humerus should be. For once the Beeb seems to have resisted the temptation of going gullible.

As for the strangely persistent notion that wild leopards or black panthers roam the countryside, it’s funny how every photograph shows an ordinary pussy cat in the distance once you work out the scale of the objects around it. The Telegraph breathlessly reported this summer that a “TV presenter” (a warning in itself) had filmed a big cat. The video, short, blurred and through a hedge, was of a… cat. Yet BBC Autumnwatch presenter Iolo Williams told a newspaper that “just because I’ve never actually clapped eyes on one living in the wild doesn’t mean to say that they are definitely not around.”

I devoured this stuff when I was about ten years old, feasting on every Sasquatch sighting and monster mystery, but then I grew up. Now it’s adults on the BBC who are pushing such pseudoscience for clicks. I am unsure what has caused this outbreak of gullibility in the mainstream media. Plummeting budgets, plunging viewing figures, click-chasing and a dose of nostalgia may all be part of it, but surreptitious messages from an advanced civilisation on Planet Zog cannot be ruled out. The BBC has an enormous team devoted to debunking things, called Verify, but it appears to have been conspicuously absent from checking its own stories.

Every time I worry that we are sinking into a new age of gullibility, I remember my own experience with the phenomenon of crop circles. When these started appearing in British wheat fields in the early 1990s I was staggered to find that even quite sane people were convinced they were made by aliens, when it was blindingly obvious that they were made by people. So I went out and made some to prove it was easy. A TV producer commissioned some students to make one and then got a silly “expert” to say on camera that it could not possibly be manmade. The two men who started the craze, Doug Bower and Dave Chorley, owned up to making them as a prank after an evening the pub. Yet still the gullible media — including even Science magazine — insisted on calling them unexplained.

I looked up the BBC’s recent pronouncement on the topic and was unsurprised that as recently as two years ago the corporation was spouting debunked nonsense again. Doug and Dave were dismissed to make way for a lot of hand waving about ley lines, spiritual energy and “extraterrestrial intelligence attempting to warn humanity about climate change.” And as for being manmade: “Among those who discount the alien hypothesis, a common theory is that human circle makers ‘tap into’ some kind of collective consciousness.”

There is a case for remaining open-minded about everything, but as someone once said: not so open-minded your brains fall out.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.