We’re entering the post-liberal moment. From Trump to Brexit, Ireland to Brazil, we’ve seen a number of revolts at the ballot box that point to a mass vote of no-confidence in the economic and cultural status quo — in other words, in 21st-century liberalism.

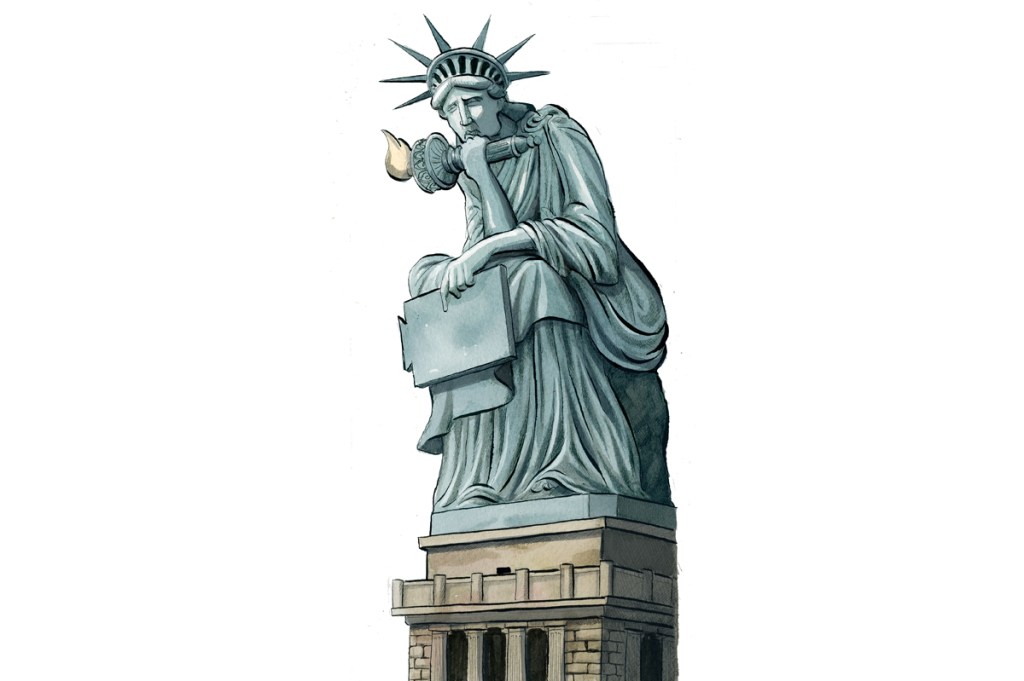

The liberals aren’t taking it lying down. They’re doing their best to define post-liberalism in language they are most comfortable with, calling it ‘fascist’ or ‘communist’ — and sometimes the criticism is spot-on. But other times it is wholly inaccurate. One of the glaring paradoxes of the post-liberal moment is that many of the people involved in it want to rescue liberalism from itself.

Error number one is to assume that post-liberalism is a vast right-wing conspiracy. Sinn Féin’s recent success in the Irish elections was plainly a left-wing revolt against liberal economics. Fianna Fáil crashed the economy with casino capitalism; Fine Gael pulled it back from the brink with austerity, but at a cost. Outsiders often champion Ireland as proof that tax cuts and globalization can make a country richer and, yes, on paper they have, but the experiment has also bred inequality and alienation: house values have soared, along with rents, and almost 4,000 children are now thought to be homeless. Sinn Féin, for all its horrific faults, was the one party uncompromised by Ireland’s spiritually vacuous political consensus.

To use the word ‘spiritually’ will seem strange to many readers because our liberal order rests on a myth of rationality — that what the voters want, and what works best, is that which is scientific and devoid of ideology. But what we’ve discovered in recent years is that for many voters this isn’t enough. They want to belong to something, and the politics of belonging operates on an emotional level that modern liberals aren’t comfortable with.

Liberalism aims to liberate and elevate the individual. This is very appealing, but it has maximized our freedom at the expense of the ties that bind us to place and people: faith, family, community, class, nation. To repeat, this is not an inherently right-wing critique. For the past three decades, various thinkers — Fred Dallmayr, John Gray, Frank Furedi, Phillip Blond, John Milbank — have warned their fellow progressives that individualism comes at the cost of solidarity, and that solidarity is just as important to the happiness of the individual as autonomy or choice.

We can’t blame liberalism for the unstoppable march of technology, but liberalism has destroyed some of the associations and traditions that might have helped us cope with that change. Some people, the ones David Goodhart calls ‘Anywheres’, have taken advantage of their newfound freedom and flourished; others, the people Goodhart calls ‘Somewheres’, feel left behind. One of the sad ironies of the Somewheres is that the change has been so fast and dramatic that they really have nothing to cling on to: the industries and culture that defined their ancestors are gone. The result is that they hanker not for their own childhoods but for those of their parents and grandparents — for a world in which we were ‘all in it together’. Many supporters of Brexit identify the 1950s as the last time Britain had it so good, while Labour activists imagine the Attlee government of 1945 was the apogee of socialism.

Nostalgia is often an illusion: the best argument against it, P.J. O’Rourke has said, is dentistry. But the fact that millions of voters are reaching back into a fantasy past is a damning indictment of the present. Liberals have not helped matters by responding with snobbery, by calling their opponents ‘unreasonable’ — on the grounds that, as liberalism is pure reason, questioning it must equate to madness or idiocy.

The problem with that conceit is that liberals in power have made mistakes so ridiculous they can only be understood as the product of blind ideology (Iraq, the credit crunch). The logic of liberalism has led liberals to make common cause with people and projects that push reason to its illiberal limits, as when identity politics activists insist that to protect their own freedom, they need to place limits on other people’s.

Conservatives in particular feel under attack, and that causes them to question parts of the liberal consensus they’ve long regarded as sacrosanct. They accuse the courts of bias, education of brainwashing their children and even big business of going ‘woke’. America’s religious right suspects that the separation of church and state only goes one way: that while Judeo-Christian values are squeezed out of government, the state is increasingly interested in telling churches what to do, even what to believe. The philosopher Patrick Deneen argues that none of this is a bug of liberalism — it is a feature. In order to guarantee liberty, he says, liberalism requires a strong state capable of protecting the individual. The further freedom expands, the bigger the state grows, both to pick up the pieces of our bad decisions and to police any threats against liberalism itself.

This helps explain the constituency for Trumpism. On the one hand, Trump wants to break up the liberal state and smash its institutions. On the other, he represents a generation of conservatives who rather admire how liberals have used the state to further their cultural cause — and who want to do the same. Trump is an agent of protectionism: protection of American jobs and protection of American culture (at least as he defines it). In a sense, that’s exactly what post-liberalism is: the attempt to preserve or restore that which is imperiled by the race to get rich.

But how does this agenda work in practice? Well, accepting that Trump’s room for maneuver is constitutionally limited, what he has gotten away with is boilerplate Republican: tax cuts, deregulation, a war on universal healthcare. Some man of the people. The real test of conservative post-liberalism isn’t whether or not it talks about rebuilding community (talk is cheap). It’s if it is willing to redistribute a bit of cash to do it — and to constrain, not encourage, the destructive free market.

This is the grand dilemma facing the Conservatives in Britain as they decide what kind of Brexit to pursue. Free trade or social-democratic? The vote to leave the EU was a key post-liberal moment: the EU is the world’s biggest liberal experiment, an attempt to replace national self-determination with free trade and open borders, governed by institutions that place an emphasis upon individual rights.

Yet many Brexiteers are themselves liberals: they interpret the EU as a socialist racket and Brexit as an escape into the globalized economy. They offer a future that a substantial part of the Brexit constituency, perhaps a majority, instinctively opposes: a low-tax, low-regulation economy modeled on Singapore (never mind that Singapore intervenes in its economy all the time and is very socially conservative). The reality is that many people voted for Brexit not to speed up social and economic change but to put the brakes on, to take a pause and, to translate Sinn Féin, be ‘we ourselves’ again. All of this poses a conundrum for Boris Johnson. He is liberal to his fingertips, yet he’s only where he is thanks to a popular desire to pause the clock, if not turn it back.

The confusion of aims and policies on both sides of the Atlantic can be explained simply: the goal of post-liberals is to preserve tradition, but being westerners, their pre-eminent tradition is liberalism, so that’s what they find themselves defending.

It’s very hard for even the most pronounced post-liberals to think of alternatives to liberalism, because they have such a strong investment in its structures and benefits. No post-liberal party today wants to end democracy (on the contrary, they tend to have a higher estimation of it than liberals do), just as very few social conservatives want to outlaw gay marriage where it has been legalized (sexual freedom and privacy are almost completely embedded in our culture). Many post-liberals (disingenuously or not) frame their opposition to mass migration as an attempt to protect liberal ideals, including gay rights, from Islamism, and a surprising number of post-liberals have allied with feminists in their critique of transgenderism. Socialist post-liberals tend to want to reform capitalism in order to save capitalism, just as conservatives claim (honestly or not) to want to depoliticize the judiciary precisely because they want to restore faith in it.

Liberals are absolutely right to be wary of the return of bigotry or authoritarianism under the guise of populism, but they need to recognize that many apparent radicals are actually looking for ways to preserve historical liberalism. One could even extend that to the green movement. Yes, some greens want to destroy capitalism, but most are asking, ‘What sacrifices are necessary in order to save what’s best about our way of life?’

Liberals could respond to post-liberalism by doubling down, calling their opponents ‘deplorable’ and gambling that the younger generation — more mobile and diverse — will rescue the system when they come of age. But this strategy hasn’t worked thus far, partly because the Somewheres still outnumber the Anywheres; partly because the young, though socially liberal, feel no stake in the current version of capitalism and lean towards the far left rather than the center. The alternative to letting things run their course is to return to the line of argument of liberals in the Thirties and Forties who, faced with totalitarian threats, grimly acknowledged that if liberalism does indeed involve deconstruction then they need to think harder about what they wish both to build and preserve based upon their own tradition, to fashion a unifying identity around being liberal in the best meaning of that word — ‘liberality’ and ‘generosity of spirit’.

As W.H. Auden said, ‘We must love one another or die.’

This article is in The Spectator’s April 2020 US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.