In the 1990s film The Usual Suspects, the detective character explains how to spot a murderer. You arrest three men for the same killing and put them in jail. The next morning, whoever’s sleeping is your killer. That’s because the nightmare of being on the run is over. It’s a relief to be caught. ‘You get some rest: let your guard down, you follow?’ I sometimes wonder if it’s the same for leaders arrested for crimes against humanity, a Karadzic or a Milosevic — and whether President Assad of Syria has the same feeling of being hunted. It’s true he has won the civil war and might think his position is secure. Yet there are several ways he might one day end up facing a war crimes prosecution.

These thoughts are prompted by news from the city of Homs. The regime disclosed that an opposition activist known as Jeddo had died in prison. He was from a suburb of Homs called Baba Amr, which was one of the first parts of the country to fall under rebel control, the ‘cradle of the revolution’. Every foreign journalist who went there knew him. Before the revolution, he’d had a shop selling vegetables. When street protests started, he picked up a video camera and became a ‘citizen journalist’. His real name was Ali Othman, but a few premature lines on his weathered face had earned him the nickname Jeddo, or Al Jed, ‘the grandfather’. He had jug ears, a ready, gap-toothed smile, and absolutely no fear of death.

In February 2012, the regime began a relentless artillery attack on Baba Amr. Al Jed took us out in his little Suzuki jeep to have a look. The air was filled with a terrible sound of booms and crashes — the government shells — and a constant crackle of rifle fire — the rebels, using almost the only weapons they had. Jeddo rolled his jeep to a gentle stop in the centre of a crossroads to point out a smoking hole in the wall of a mosque. That’s very interesting, I told him, trying not to flinch with each crash, but perhaps we ought to move? No, no, he said, unconcerned, we’re fine. This went back and forth for an agonizingly long minute, my voice increasingly strained; Jeddo was relaxed, just out for a Sunday drive. Finally, he did a three-point turn of infinite slowness and drove away. Another shell landed, covering the place we’d stopped in a furiously billowing black cloud.

It seemed as if he had gone a little mad because of the constant danger. I think now that it was something else: an unshakeable determination not to go back to the old days, to do anything to defeat the regime. Remembering him this week, a friend said that Jeddo had been wealthy by his neighbors’ standards (small shop, jeep); he hadn’t joined the uprising to enrich himself. ‘He wanted only freedom.’ Many of the activists in Baba Amr believed the rebels should make a stand there, whatever the cost. They knew the regime would win the battle but they thought that a massacre — filmed by citizen journalists such as Jeddo — would force the US and Europe to step in. Baba Amr would be sacrificed for the revolution. Jeddo was furious when the rebels fled, calling them cowards and dogs. ‘They are chit-chatting in Qusayr [a town miles away], watching while Baba Amr is destroyed and their women are violated.’

He told me that when we got through to his cell phone as Baba Amr fell in March 2012. He had dug a hole in his garden, ready to hide when the Syrian army kicked in the door. In fact, he managed to sneak out of Baba Amr, almost the last to leave. But he was caught a month later in a small town outside Aleppo. The story is that a female activist sent him a text telling him to come to collect some video equipment. She had been turned by the secret police, or they had her phone. A month after that, Jeddo appeared in a TV ‘interview’ from his jail cell, shown by a channel that supported the government. Nothing more was heard of him until last month, when the authorities in Homs told his family that he had died. They were given a document saying this had happened on December 30 2013. The regime had kept them waiting — in hope and dread — for more than five years.

This official document does not say how he died, though if the family ever get a death certificate it would probably have some innocuous term like ‘cardiac arrest’ or ‘respiratory failure’. That is usually the case with victims of the Syrian prison system. Jeddo’s friends say his broken appearance in the TV interview was evidence that he had been tortured. They could not imagine him doing the interview at all unless forced to. The Syrian Network for Human Rights says that almost 14,000 people have been tortured to death in Syrian prisons. Jeddo’s family and friends assume this is what happened to him. A fellow activist told me he didn’t want to believe it but said: ‘He’s better off dead.’

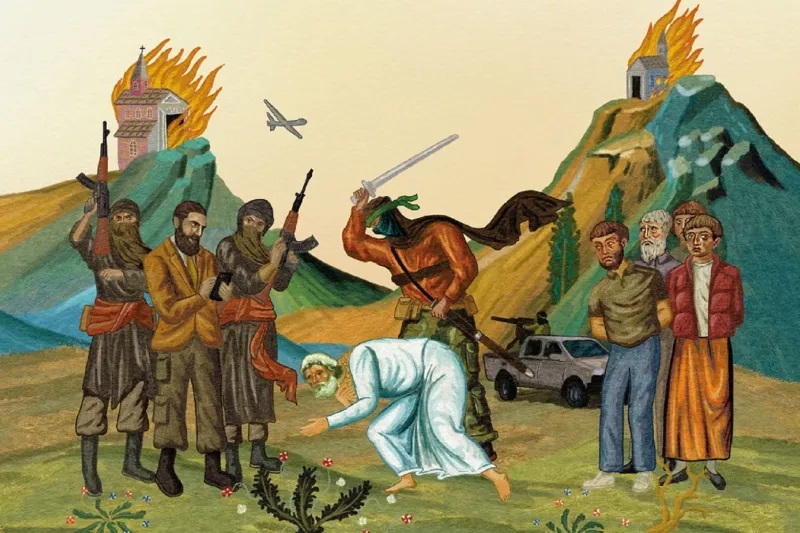

The activists know all too well what happens in Syrian prisons. One survivor told the press this week about a guard who called himself Hitler and who made prisoners get down on all fours and bark like dogs or bray like donkeys. Prisoners were stripped naked and beaten, hung from wires, soaked with cold water, starved and forced to fight one other, even to kill other inmates. A report from the UN Human Rights Council quotes a man who was held in the Damascus Political Security Branch. ‘The officer took two girls, held their faces down on the desk, and raped them in turn. [He] told me, “You see what I am doing? I will do this to your wife and daughter.”’ Sexual violence is common. I once interviewed a government militiaman captured by the rebels who said — with no trace of emotion — that his job had been to rape women arrested at anti-government demonstrations. All these stories speak of systematic torture. It is policy. No one in Syria believes otherwise, whatever the regime’s public protestations.

A body called the Commission for International Justice and Accountability — funded by several western governments — has been investigating President Assad’s culpability. They are not trying to prove he is guilty of this or that specific war crime, but that he runs a system where such crimes are routine, so-called command responsibility. They have collected some 800,000 documents — the Syrian regime is meticulous in its bureaucracy, everything written down. The organization’s spokesperson, Nerma Jelacic, told me the evidence against Assad was ‘very strong’. The idea was to have a case ready to go immediately if Assad were arrested.

President Assad knows enough not to travel to any western countries. Russia will use its veto in the UN Security Council to stop the creation of a Syrian tribunal at the Hague. But some argue that the UN General Assembly could vote for the tribunal by a two-thirds majority. And Assad might be toppled, not by the rebels but as a result of the regime’s vicious internal politics. President Milosevic of Serbia thought he was safe from the Hague until a successor handed him over. General Pinochet went to London for medical treatment and was arrested on human rights charges. Philippe Sands, a QC who knows this area of law better than anyone, says a war crimes prosecution hangs over Assad ‘like a sword of Damocles… A leader needs to know the possibility of justice is real.’ He would not be surprised to see Assad in the dock eventually. For a large part of the Syrian population, the war will not be over until he is.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.