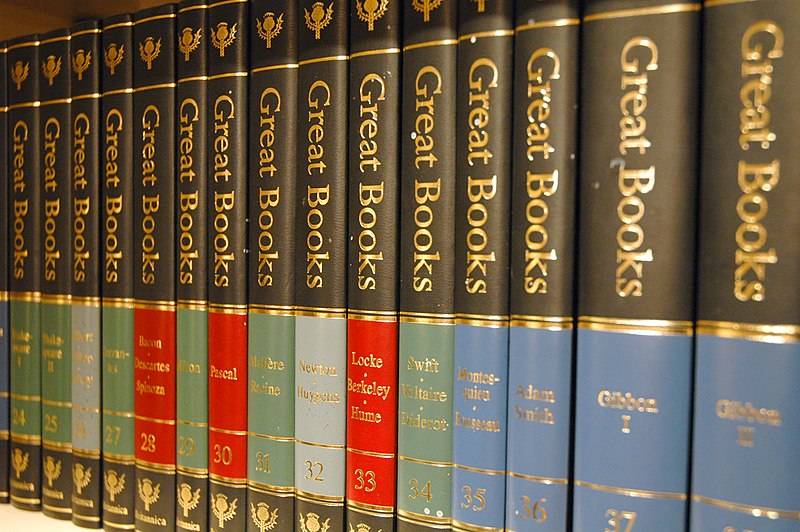

In this week’s New Yorker, Louis Menand reviews two books that defend a Great Books curriculum — Roosevelt Montás’s Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation and Arnold Weinstein’s The Lives of Literature: Reading, Teaching, Knowing. He doesn’t like either.

Both authors claim that great works of literature shape our lives for the good and that this sort of moral or personal approach to texts is undervalued at modern universities, which, in turn, are more concerned about vocational training and marketable skills. English and comparative literature departments — are there any of those left? — emphasize specialization and ignore wisdom. Critical theory and cowardly administrators who cave to the slightest demand to remove works that offend have only made things worse. Something must be done. Hence, these books.

Menand, who is not entirely against this argument, reminds us that this is an old debate: “The quarrel between generalist and specialist—or, as it is sometimes framed down in the trenches, between dilettante and pedant—is more than a hundred years old.” Menand is referring to the debates in English between the philologists and humanists. But the debate is much older than that. In one of his letters to Lucilius, Seneca argues famously that liberal studies do not make students virtuous. This was somewhat against the grain at the time. He states emphatically that liberal studies — in poetry, astronomy, mathematics, history — offer “nothing” in terms of virtue. Yet, he continues, students should still study poetry because it “prepares the ground” for virtue:

“Why then do we educate our sons in liberal studies?” Not because they can confer virtue but because they prepare the mind to receive it. Just as what long ago used to be called basic grammar, by which children acquire the rudiments of their education, does not teach the liberal arts but prepares the ground for them to be acquired in due course, so the liberal arts themselves do not lead the mind to virtue but clear the way for it.

Menand’s problem with the claims that Montás and Weinstein make for great books is that they are too big:

The humanities do not have a monopoly on moral insight. Reading Weinstein and Montás, you might conclude that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth. Take my word for it, we are not. We are not better or worse than anyone else. I have read and taught hundreds of books, including most of the books in the Columbia Core. I teach a great-books course now. I like my job, and I think I understand many things that are important to me much better than I did when I was seventeen. But I don’t think I’m a better person.

I agree with Menand here, and the problem is not limited to defenses of “great books.” In book after book on the value of reading, the argument is made that literature improves us. The authors differ on what improvement means — literature makes us kind, just, holy, free; the list goes on — but the approach is the same, and the claims for the power of literature are almost always far too big.

At the same time, works of literature are more than just records “of the ways human beings have made sense of experience,” as Menand writes. That reduces them to mere artifacts and transforms the reader into a kind of anthropologist. I prefer Seneca’s approach.

In other news

What so-called Big History misses: “Sweeping the human story into a cosmic tale is a thrill but we should be wary about what is overlooked in the grandeur.”

The new Musée Carnavalet: “Now, for the first time, visitors can move relatively seamlessly from the 6,000-year-old canoe found near the Seine at Bercy, housed in a new basement display on Paris from prehistory to the medieval period, through to relics of Parisian history in the 21st century, including a large cardboard pencil proclaiming ‘Je Suis Charlie’, from 2015, and photographs of Parisians watching Notre-Dame burn in 2019.”

Christmas with Hemingway in Arkansas: “Ernest Hemingway married his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, on May 10, 1927. The newlyweds made their way from Europe to Piggott, Arkansas. She was pregnant and wanted to be closer to her family before the birth of their son, Patrick. Hemingway worked on his novel A Farewell to Arms in the barn/studio behind the house, located on West Cherry Street in what is now the center of town . . . Hemingway loved Piggott and Pauline’s family. He told Esquire magazine in 1934 that the only other place he would rather be in than Paris was ‘Piggott, Arkansas in the fall.’”

Charles Dickens’ other Christmas stories: “It is the story of a miserly gentleman who eventually finds redemption, and it was a huge bestseller in its day, but Charles Dickens’ festive story The Cricket on the Hearth is far less well-known than its predecessor A Christmas Carol.”

John McWhorter in the New York Times: “Porgy and Bess isn’t Black opera. It’s American opera.”

The Guardian has one million users that pay for digital content on a recurring basis. Three years ago, that number was just above 500,000.

David J. Garrow reviews Claude A. Clegg III’s The Black President:

Clegg is too good a historian to be an uncritical fanboy like the many journalists who forfeited their professionalism during the Obama years. He grasps the hopeful ambivalence with which many black Americans responded to the “boundless ambition” of Obama’s self-created life-story, noting how the comedian Chris Rock called him “our zebra president. …We ignore the president’s whiteness, but it’s there.” Likewise, the distinguished actor Morgan Freeman bluntly observed that “He’s not America’s first black president, he’s America’s first mixed-race president.” Clegg also grapples forthrightly with the reluctant yet widespread recognition that Obama’s presidency failed black Americans to a painfully surprising degree.