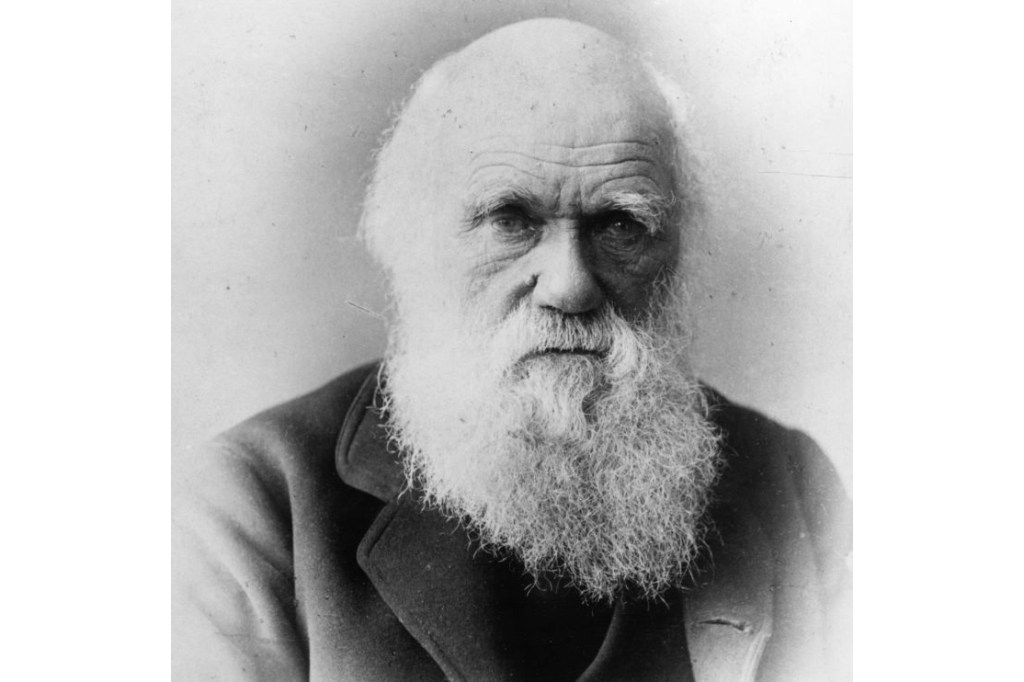

Have you noticed that whenever the conversation turns to the subject of Charles Darwin, an extraordinary amount of dogmatism is often on view?

What’s curious is that the dogmatism is patent on both sides of the debate, on the side of the Darwinists just as much as the side of Darwin’s critics.

I have often noted with amusement how sensitive to criticism the Darwinian faithful are. Any hint of a shadow of dissent and they rush for the garlic, the wooden stake and a signed copy of On the Origin of Species.

I think I understand the psychology of the response. They are terrified lest acknowledging the strength of this or that criticism start them down the road toward creationism and teaching the Book of Genesis in Biology 101.

Where does the truth lie? Are the main doctrines of Darwinian teaching as impregnable and well established as proponents claim?

One good place to start for an answer is with Darwinian Fairytales, the last work of the Australian philosopher David Stove. By the time of his death in 1994, Stove had earned a distinguished place for himself in the pantheon of intellectual demolition experts.

His targets, one admirer wrote, are many: “the Enlightenment, feminism, Freud, the idea of progress, leftish views of all kinds, Marx… metaphysics, modern architecture and art, philosophical idealism, [Karl] Popper, religion, semiotics, Stravinsky and Sweden… Also, anything beginning with ‘soc’ (even Socrates got a serve or two).”

High among Stove’s antipathies was irrationality in the philosophy of science, which he detected not only in overt irrationalists such as Paul “Anything Goes” Feyerabend but also in more seemingly respectable figures such as Thomas “Mr. Paradigm Shift” Kuhn.

If you believe (as your teachers doubtless told you) that Kuhn or Karl Popper was a friend of honest scientific inquiry, read Stove’s book Scientific Irrationalism: Origins of a Postmodern Cult. I guarantee that it will change your mind.

A century ago, William James wrote a book called The Varieties of Religious Experience. Had Stove lived long enough, he might have written something called The Varieties of Irrational Experience. His hilarious but disturbing essay “What is Wrong with Our Thoughts?,” reprinted in The Plato Cult and Other Philosophical Follies, would make a splendid introduction to such a work.

I want to pause to emphasize the hilarity. Stove was one of the greatest philosophical stylists of our, perhaps of any, time. That is a large claim, I know, but don’t take my word for it: read his work. You will see why one commentator wrote that reading David Stove is like watching Fred Astaire dance: the elegance, the seeming effortlessness, are breathtaking demonstrations of consummate artistry.

Stove’s skeptical cast of mind (David Hume was his philosophical hero) naturally endeared him to the enemies of cant, the exposers of naked emperors, the puncturers of academic gasbags, poseurs and charlatans.

How surprising, then, that David Stove should turn out to be an ardent anti-Darwinian.

Wasn’t Darwin on the side of all us Enlightened, no-nonsense, scientifically educated folk? If David Stove criticizes Darwin’s theories, doesn’t that make him an irrationalist, an ally of those school boards in Kansas that (or so we are told) want to replace science with scripture?

No, it doesn’t.

For one thing, Stove is not a creationist or proponent of “intelligent design”; indeed, he is careful to point out that he is “of no religion.”

Moreover, Stove admires Darwin greatly as a thinker, placing him at the top of his personal pantheon, along with Shakespeare, Purcell, Newton and Hume.

Stove furthermore believes that it is “overwhelmingly probable” that our species evolved from some other and that “natural selection is probably the cause which is principally responsible for the coming into existence of new species from old ones.”

Indeed, he believes that “the Darwinian explanation of evolution is a very good one as far as it goes, and it has turned out to go an extremely long way.” Its explanatory power, Stove noted, was obvious from the moment it was published in 1859. Darwin wrote before the discovery of genetics, but that science only increased the explanatory strength of Darwinian theory.

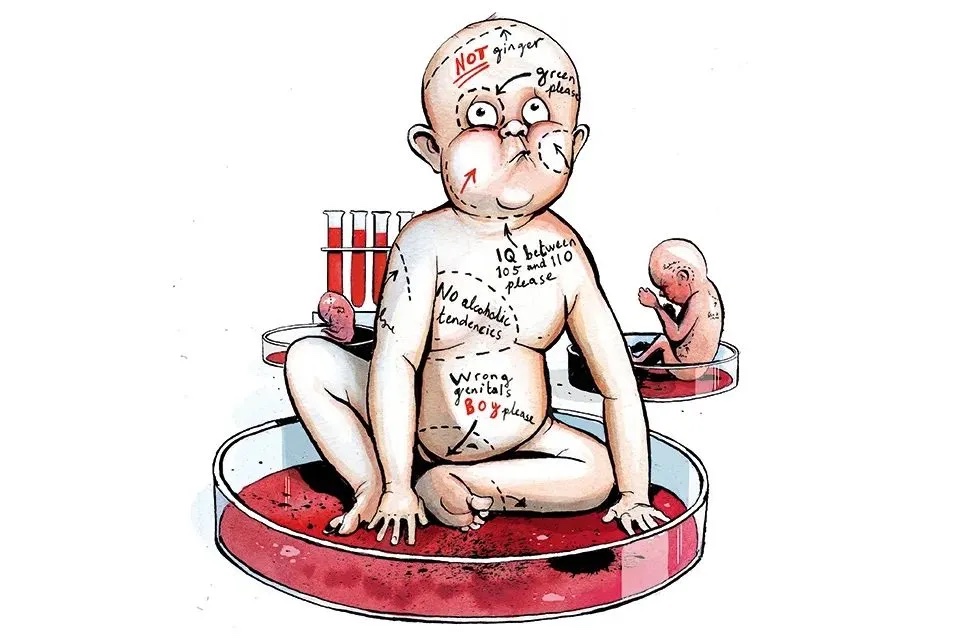

At the same time, though, Stove maintains that “Darwinism says many things, especially about our species, which are too obviously false to be believed by any educated person; or at least by an educated person who retains any capacity at all for critical thought.”

Examples? Here are a few: that “every single organic being around us may be said to be striving to the utmost to increase its numbers”; that “of the many individuals of any species which are periodically born, but a small number can survive”; that it is to a mother’s “advantage” that her child should be adopted by another woman; that “no one is prepared to sacrifice his life for any single person, but… everyone will sacrifice it for more than two brothers, or four half-brothers, or eight first cousins”; that “any variation in the least degree injurious [to a species] would be rigidly destroyed.”

All of these quotations are from Darwin or his orthodox disciples. A moment’s reflection shows that none is even remotely true, at least of human beings.

Take the last named: that anything in the least injurious to a species would be “rigidly destroyed” by natural selection.

What about abortion, adoption, fondness for alcohol, anal intercourse or asceticism, just to start with the “A”s? As Stove notes, “each of these characteristics [tends] to shorten our lives, or to lessen the number of children we have, or both.” Are any on the way to being rigidly destroyed?

Again, if Darwin’s theory of evolution were true, “there would be in every species a constant and ruthless competition to survive: a competition in which only a few in any generation can be winners. But it is perfectly obvious that human life is not like that, however it may be with other species.”

Priests, hospitals, governments, old-age homes, charities, police: these are a few of the things whose existence contradicts Darwin’s theory.

Some of Darwinism’s defenders respond by arguing that although human life may not now exhibit the brutal struggle for subsistence that Darwin’s theory postulates, it once did.

Stove is very good on this canard: “In the olden days (this story goes), human populations always did press relentlessly on their supply of food, and thereby brought about constant competition for survival among the too-numerous competitors, and hence natural selection of those organisms which were best fitted to succeed in the struggle for life.”

“That is,” Stove continues, “human life was exactly as Darwin’s book had said that all life is. But our species (the story goes on) escaped long ago from the brutal regime of natural selection. We developed a thousand forms of attachment, loyalty, cooperation and unforced subordination, every one of them quite incompatible with a constant and merci- less competition to survive.”

This is what Stove calls the “Cave Man” attempt to solve “Darwinism’s Dilemma.” (The other attempts he calls the “Hard Man” and the “Soft Man” gambits).

But the problem is that Darwin’s theory is not meant to be something that was true yesterday but not today. It claims to be, as Stove puts it, “a universal generalization about all terrestrial species at any time.” And this means that “if the theory says something which is not true now of our species (or another), then it is not true — finish.”

Stove writes: “If Darwin’s theory of evolution is true, no species can ever escape from the process of natural selection. His theory is that two universal and permanent tendencies of all species of organisms — the tendency to increase in numbers up to the limit that the food supply allows, and the tendency to vary in a heritable way — are together sufficient to bring about in any species universal and permanent competition for survival, and therefore universal and permanent natural selection among the competitors.”

But this is clearly not true of our species now. Nor, Stove points out, can it ever have been true of our species.

“It may be possible, for all I know, that a population of pines or cod should exist with no cooperative as distinct from competitive relations among its members. But no tribe of humans could possibly exist on those terms. Such a tribe could not even raise a second generation: the helplessness of the human young is too extreme and prolonged.”

Stove shows in unanswerable detail that, despite its enormous explanatory power regarding “cods, pines, flies,” etc., Darwin’s theory of evolution is “a ridiculous slander on human beings.”

He is particularly good at exposing the “amazingly arrogant habit of Darwinians” of “blaming the fact, instead of blaming their theory” when they encounter contrary biological facts.

Doctrinaire Darwinists have an answer for everything, always a bad sign in science, since it means that mere facts can never prove them wrong.

Does it regularly happen that increasing prosperity leads to lower birth rates? And does this directly contradict Darwinian theory? No problem, just announce that the birth rates in such cases are somehow “inverted,” evidence of a “biological mistake.”

Even more amusing is to watch a sociobiologist tie himself in knots trying to explain — or explain away — the phenomenon of altruism among human beings. The latest wheeze is something called “inclusive fitness” which attempts to deal with the “problem” of altruism by transforming it into a surreptitious form of selfishness.

Darwinian theory says that really, deep down, altruism cannot exist: we’re all engaged in a war for survival, after all.

And yet, as Stove points out, our species “is sharply distinguished from all other animals by being in fact hopelessly addicted to altruism. It will be time to think otherwise when, and not before, adult wolves or kookaburras or rats pool their resources in order to relieve the illness, or improvidence, or ignorance, of conspecifics to whom they are unrelated.”

Stove is also very good at exposing the mind-boggling claims of sociobiology — aka evolutionary psychology — a school of neo-Darwinism whose fundamental tenet is that an organism is epiphenomenal to its genes: that a human being, for example, is nothing more than a puppet manipulated by his genetic makeup.

If this seems like an exaggeration, consider the statement by the eminent sociobiologist E. O. Wilson that “an organism is only DNA’s way of making more DNA.” It is worth pausing to ponder the implications of that adverb “only.”

Or consider Richard Dawkins, another eminent sociobiologist and author of The Selfish Gene, a hugely popular book whose basic message is that “we are… robot-vehicles blindly programmed to preserve the selfish molecules known as genes.” (Yes, Dawkins really says this.) Of course, as Stove points out, “genes can no more be selfish than they can be (say) supercilious, or stupid.”

The popularity of Dawkins’s book lies in the powerful appeal that puppet-theories of human behavior always exercise on those who combine cynicism with credulousness; but genetic puppet theories are no more credible than those propounded by Freudians, Marxists or astrologers.

In the end, Stove’s discussion of Darwinian theory shows that, when it comes to the species H. sapiens, Darwinism “is a mere festering mass of errors.”

It can tell you “lots of truths about plants, flies, fish, etc., and interesting truths, too… [But] if it is human life that you would most like to know about and to understand, then a good library can be begun by leaving out Darwinism, from 1859 to the present hour.”

It is not a pretty picture that Stove paints; but then the exhibition of gross error widely accepted is never a comely sight.

Leave a Reply