“Please accept coffee without payment. You are visitors.” So said the manager of the retro-chic little Café Auber in downtown Algiers, where we’d paused on a stroll down to the harbor after Christmas. We’d considered the city just a stop on our way into the Sahara. Instead it proved a revelation.

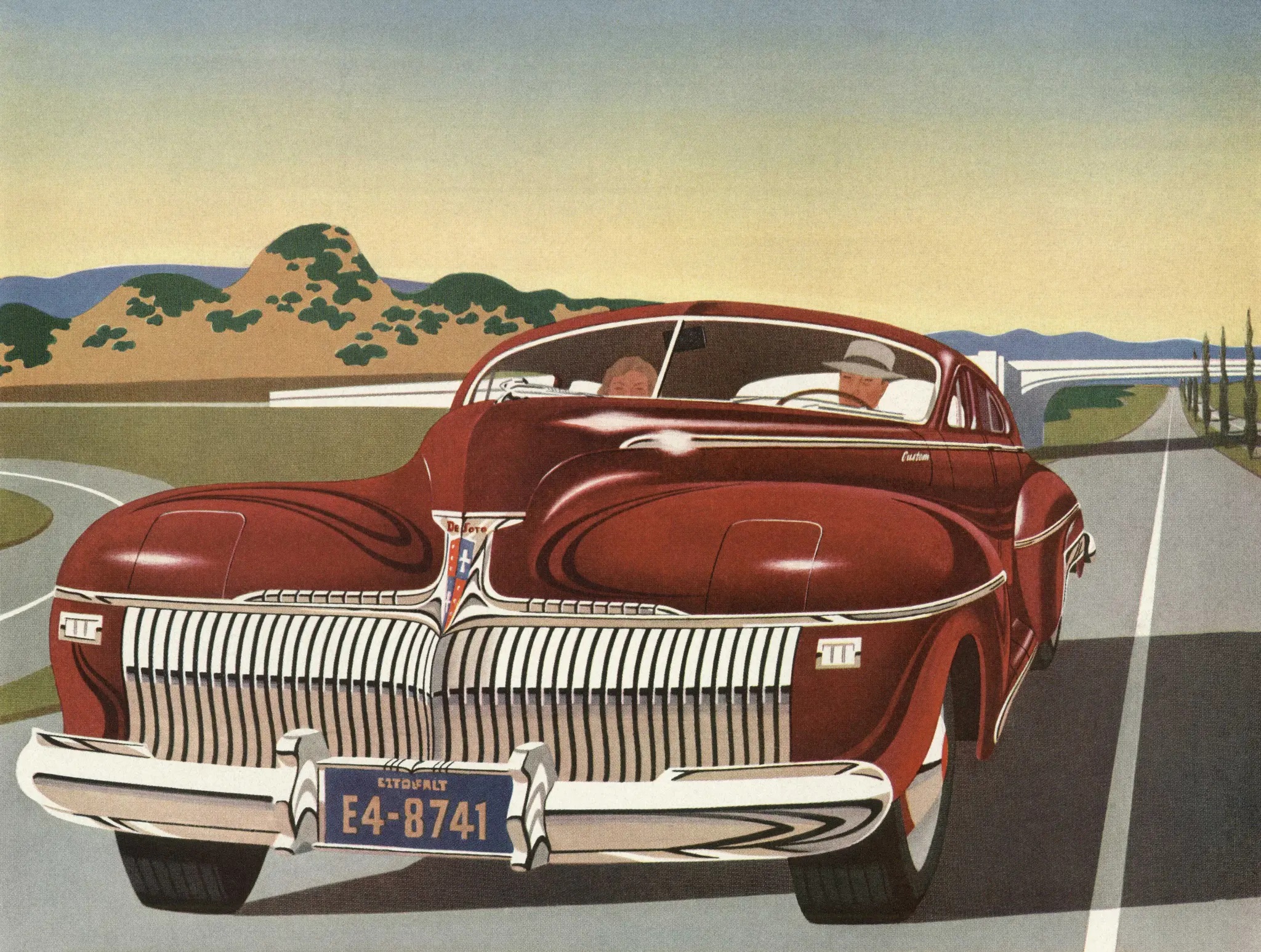

Were you to arrive at Algiers on one of the regular overnight ferries from Marseille, you would be greeted by a waterfront of magnificent, ornate, turn-of-the-nineteenth-century mansion blocks: Parisian-style, cream and white, embroidered with palm trees. Built in the grand French style, the old city rising up the hillside behind remains astonishingly true to its history, though it’s more than half a century since France quit her former possession after the bloodiest war of liberation in modern history. Narrow streets and long flights of granite steps thread between five- and six-story residential edifices whose stucco facades proclaim variously the Gallic confidence of the 1880s, early twentieth-century modernism, or the stylish curves of the 1930s. Do the stray cats padding through this living relic of another age, another culture, know their provenance?

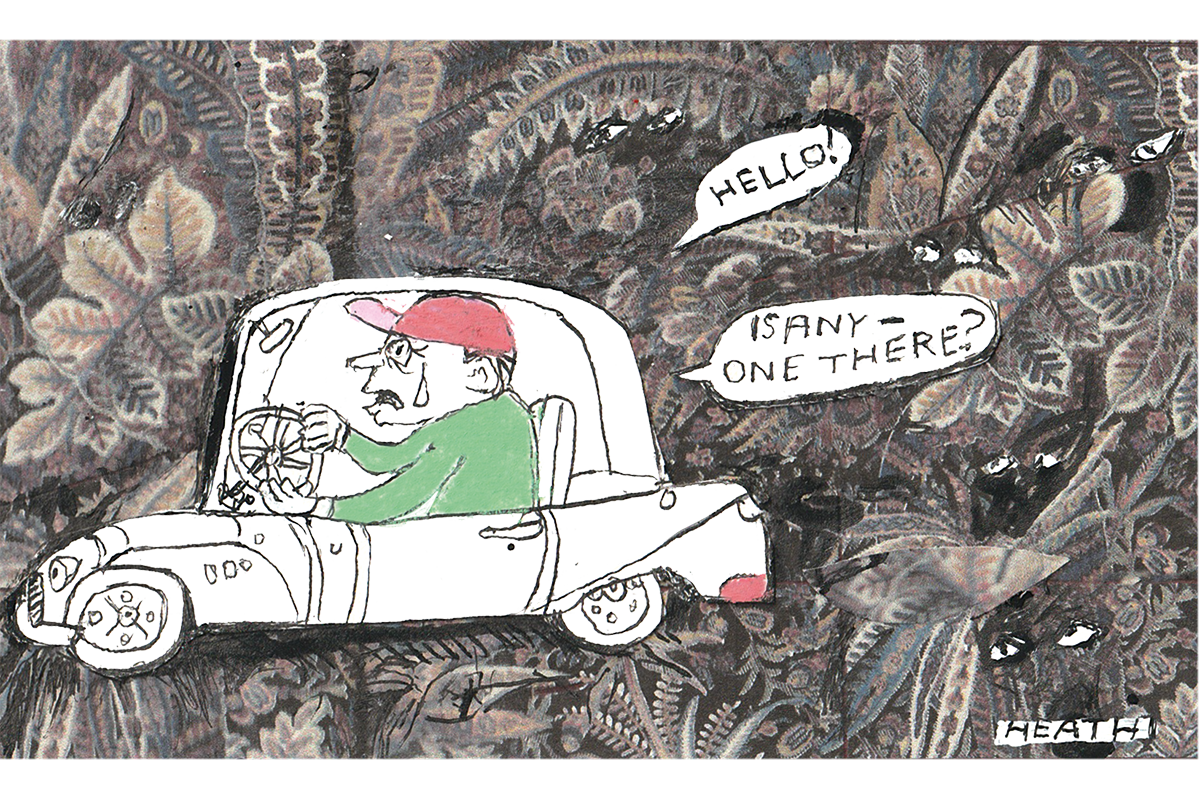

Venture up those unending steps or down through the dark alleys, the traffic-choked streets and busy cafés, and your first impressions become laced with a thrilling sense of gentle decay. The cats thrive on overflowing bins, and the inheritors of this once-imperial city, its modern and overwhelmingly Arab Algerian population, jostle, promenade, tarry or hurry about their business. New Algiers sprawls unmemorably for miles, but old Algiers is not dying, just fraying somewhat at the seams — and now some impressive repair and restoration is under way. As one of the city’s still-uncommon European tourists, you will be entirely safe, frequently lost, often guided, and always noticed.

Simon Calder, the Independent’s free-ranging travel expert, puts Algeria at the top of his list of recommended destinations for 2024, and he’s not wrong. But we — my three companions and I — anticipated Calder, escaping a rainy English Christmas for the Saharan sun in the mighty Hoggar mountains, as far south of Algiers in this vast country as Algiers itself is south of London.

First, adjust your expectations. This is not a third-world country, but nor is it first-world. There’s a big middle class; a bit of English (and a diminishing amount of French) is spoken, especially by the young; and Algerians are quietly welcoming people. The roads are fine, domestic air services excellent, and there are decent hotels with clean ensuite bedrooms; but public facilities can be filthy, plumbing eccentric and a room where everything works would be exceptional. Huge numbers are employed as sky-blue-uniformed policemen, but they’re not bossy and will help you over the road. The economy has been liberalized but Algeria’s post-independence Marxist roots still show, bureaucracy can be tiresome, and Adam Smith’s animal spirits of capitalism are more evident at street level than higher up. There’s a thriving currency black market, so if you bring euros your money goes at least 25 percent further, making a visit good value for tourists. Restaurants are occasional, food is good, and cafés that serve those addictive little glasses of sweetened tea with mint are ubiquitous, but (though Algeria is Islamic without being Islamist) finding a bar may take a little research.

We found a professional local outfit (fancyalgeria.com) to sort things out for us at very reasonable cost, meet us, provide drivers and guides, and arrange hotels. And they got us the visas British visitors need: trying to do this yourself at Algerian consulates abroad is a tiresome business. That said, if you stick to the Mediterranean coast with its treasury of Phoenicean, Greek and Roman ruins and antiquities (we had time to see Cherchell — once Caesarea — and its splendid little museum), it would be possible to travel independently. But venturing inland by air or local coach towards the Sahara, or into the desert itself, with its fascinating oasis towns like Ghardaia, a foreigner might struggle.

Our destination was Tamanrasset, more than two hours’ flight south by Air Algérie jet. Once a base for the French Foreign Legion, this is the administrative capital of its desert region. Though tremendously enlarged since I was first there some fifty years ago, Tamanrasset remains what it has always been: a rather charmless, messy, rubbish-strewn town with a frontier feeling about the place. There is only an extreme desert of baking stones and sand for the remaining 250 miles south to In Guezzam on the border with Niger. Still, the Hotel Caravanserai was nice, and for our party of four people Tamanrasset was only the starting point for four days of sun-drenched journeying into the surrounding Hoggar mountains, and four nights of freezing camping beneath a full moon in some of the most spectacular situations I’ve ever shivered in. We warmed our hands around fires built by our jolly guide, Mustafa, his ingenious cook and his two friendly Toyota drivers.

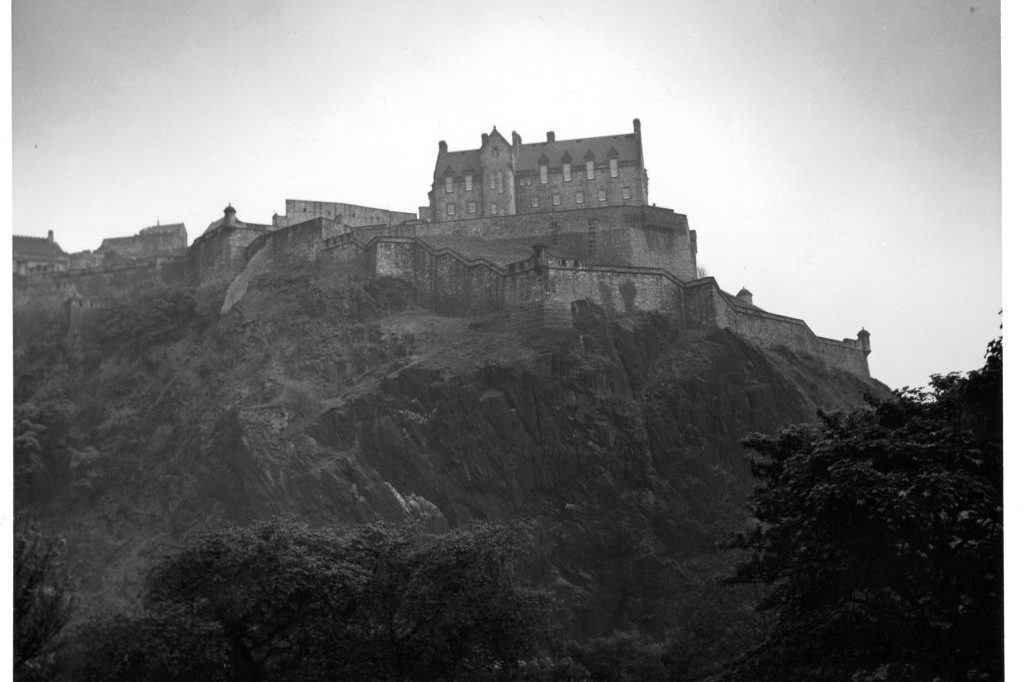

How can I describe these mountains and the 24,000 square mile Ahaggar national park in which they rise? The highest peak is some 9,500 feet, and there is barely a blade of grass to be seen on the vertiginous range of once-volcanic red-rock towers that bear a closer resemblance to skyscraper-sized pillars of basalt than what we Europeans would think of as mountains. Imagine Manhattan, but in rock.

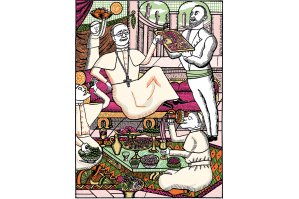

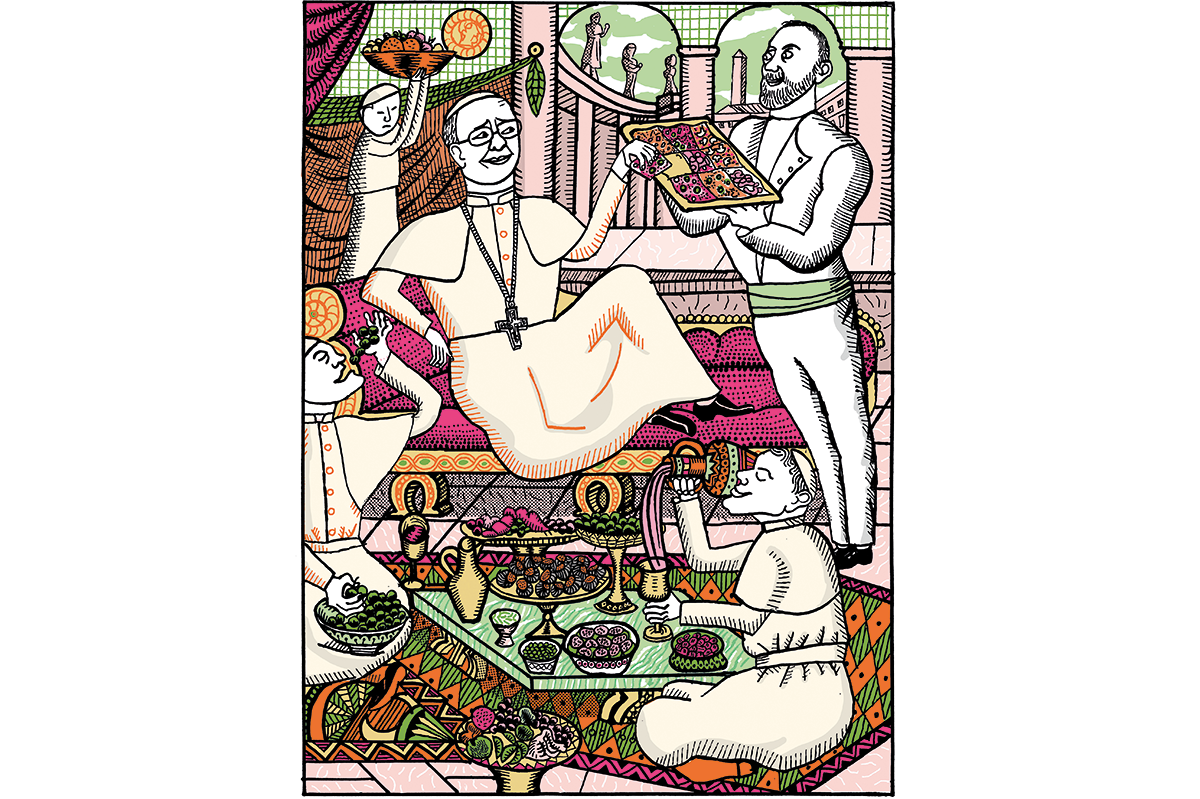

We spent a night just below the simple hermitage that Charles de Foucauld (canonised last year) built atop the 9,000ft plateau at Assekrem. Until his assassination in 1916, the monk lived often with the nomadic Tuareg tribe, of whose language he produced the first dictionary. “It is not necessary,” Foucauld wrote, “to teach others, to cure them or to improve them; it is only necessary to live among them, sharing the human condition and being present to them in love.” Eyebrows were raised (according to rumor) by his entertaining handsome young Tuareg men at this hermitage.

Watching from that mountaintop as an orange sun set over the most extraordinary encirclement of mad mountains I shall ever see, I felt momentarily close to Father Foucauld.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply