Food porn, an exaggerated photographic representation of how food supposedly looks, has been with us since the 1970s.

Today, it is as ubiquitous as “traditional” porn and just as sad. It disorders our senses. Food tastes and smells, only thirdly does it look.

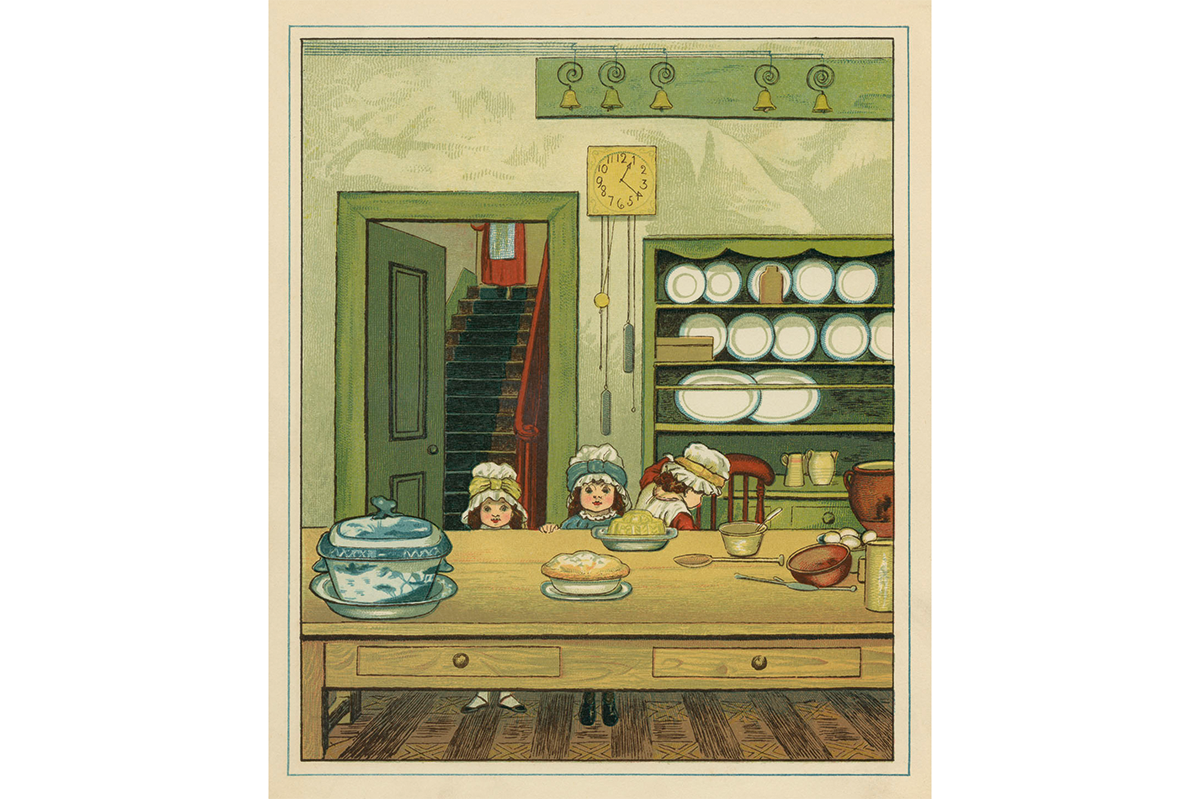

Youthful gazing through the bakeshop window is one thing; seeing food mediated through the photographic image is quite another: it titillates but does not nourish. It has been a steep fall from the innocent old days of “Oh boy, that looks good!” exclaimed in the real presence of home-prepared meatloaf or macaroni-and-cheese, not in response to a picture of it. This disordering of our senses manifests in two ways. Go on the website of just about any restaurant anywhere and you will see, not a street view of the premises, but supersaturated photos of what’s on the menu. I find this unhelpful, for all such photography looks the same and does nothing to help me discriminate between this eatery and that. Moreover, it has virtually banished something that would be helpful: images of the dining space where I would be committing two or three hours of my time. Is the ceiling high or low? Is the decor woody or metallic? Are there tablecloths and tables for two?

The second disorder is our subject here. At home, if we like to cook what we eat, the cookbooks, and today the endless web videos, that instruct us how to go about it have become photographic extravaganzas: feasts solely for the eyes, as it were, if deceptive ones.

Chances are your own dish, having merely been cooked and not studio-produced, won’t look quite like the one depicted on the glossy page. Nor should it.

In the nineteenth century and earlier, cookery books were bereft of illustration, in part due to the limits of printing technology but not, I suspect, for that reason alone. Sensibilities back then had yet to be seduced by the visual. Two classics of the Victorian age, the American Miss Leslie’s New Cookery Book from 1857 and the British Mrs. Beeton’s Cookery Book from 1861, instructed the home cook largely with words. A century later, the landmark Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961), in which Mmes. Child, Bertholle and Beck translated the great Gallic tradition for Americans, still appeared with sparse drawings, and those typically of the before, not the after, part of the project: as in “how to seed and juice tomatoes” or “how to stuff and truss a duck.”

The best and most accessible example of this old prejudice for words over pictures, and by far the most comprehensive in terms of the variety of dishes offered, is Craig Claiborne’s 700-page New York Times Cook Book, also from 1961 and comprising recipes that had appeared in the then-great Gray Lady during the 1950s. My copy, its binding broken with use (in “Meats,” between “Country Ham” and “Veal”) and messily annotated with the dates dishes were tried and the results, illustrates without illustration the abiding utility of an unpretentious instruction-manual approach to cookbooks before our obsession with sumptuous visuals took over.

Also absent from Claiborne’s classic are those chatty, it’s-all-about-me asides that let the reader in on just how and where the author discovered such-and-such wonderful dish and highlighting her wide travels and general erudition. Claiborne got around too and was certainly a sophisticated fellow, but his book is not where he told you about it. Such illustrations as it does contain (all of them black-and-white) come across as random, even humorous, as if the publisher wanted something tossed in to be able to describe the book as “illustrated.” Who, for instance, really cares how to roll up galantine of turkey, a complicated dish to say the least and seldom seen outside a proper old-fashioned French restaurant? I have never seen one “at home” or attempted it myself. The four snapshots in the Appetizers section don’t much help, and for today’s cook the turn-off comes in the first caption: “To make a galantine, a turkey or other fowl is boned. Most butchers will do this chore.” Not nowadays, they won’t.

Or consider Lobster en Bellevue Parisienne, another exotic of which we get a something-short-of-tantalizing shot of the finished product: the great crustacean lunging upward off the platter, an artichoke-laden skewer “through the lobster’s eyes,” its antennae preserved and artfully curled, claws un-cracked and menacingly open, medallions cut from the tail adorned with truffles fixed in aspic and fanned-out to decorate the top of the shell. The kitchens of Carême, not those of 1950s household cooks, come to mind here.

There’s the occasional table shot. “From the left: bouillabaisse from France, minestrone from Italy, chicken corn soup, traditionally American.” What we see are three potage-laden vessels, one decorated with fish, one sitting atop an alcohol burner, the third flanked by two candlesticks, all with a spooky cypress branch (for “atmosphere”?) reaching in from top right.

None of this triggers the desire, not mine anyway, to attempt any of these dishes. The pictures are far from the main event, access to which comes only with reading. Claiborne was a recipe writer who had mastered the two essential ingredients of the trade: clarity and concision. We’re amateurs, not professionals, who, however much we may love to cook, aren’t getting paid for it.

The recipe is the portal to a good meal prepared at home, and we want as few obstructions as possible. A list of ingredients, followed by what to do with them in numbered steps, no more no less, was Claiborne’s formula. Seventy years later, it works as well as ever, and I encourage today’s cooks, however addicted to shameless full-frontal food photography, to revert to the old ways. The only extra that Claiborne supplied to some of his recipes — sandwiched in between the subject line, (“Mushroom Bisque”), and the quantity, “About 2 Quarts,”) was the occasional light-handed editorial judgment, but a judgment nonetheless. “Although cultivated mushrooms lack the character of their wild country cousins, they are not to be scorned. They can be the basis for several highly acceptable soups.” I made this bisque, acceptably enough, for guests on New Year’s Eve 2019, who, says my note, approved, which is the test that matters.

Claiborne was onto something. “Highly acceptable” is a standard of kitchen performance actually within reach. Not “best ever,” or “transporting” or “indulgent” or other such foodie guff — just highly acceptable. Today’s deluge of food photography drowns out such sensible expectation and amounts to marketing-driven fraud. Your dish, and mine, is going to look like just what we make it look like. And whatever it looks like, if it tastes right, it will nourish our bodies and brighten our spirits: a decent reward for work well done. Cooking is craft, not art.

How a dish is put together bears study; putting it together takes attentiveness and, if you are like me, practice. There are precious few originals. Most recipes, whether for haute cuisine or down-home favorites or something in between, are the sum of countless other cooks’ experiences. With luck, our experience adds a drop or two more to a broad tradition. Recall those ladies’ charity cookbooks, reported in this space a few months back, that seem forever with us. Just like Claiborne’s and Child’s great classics, they do it in dazzling black-and-white with words, not pictures. Read the instructions and bon appétit!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.