James Eskridge cuts a defiant figure as he rides around Tangier Island on his motorbike. The weathered, garrulous water man known to all as “Ooker” is the mayor, spokesman and public face of one of America’s most endangered communities.

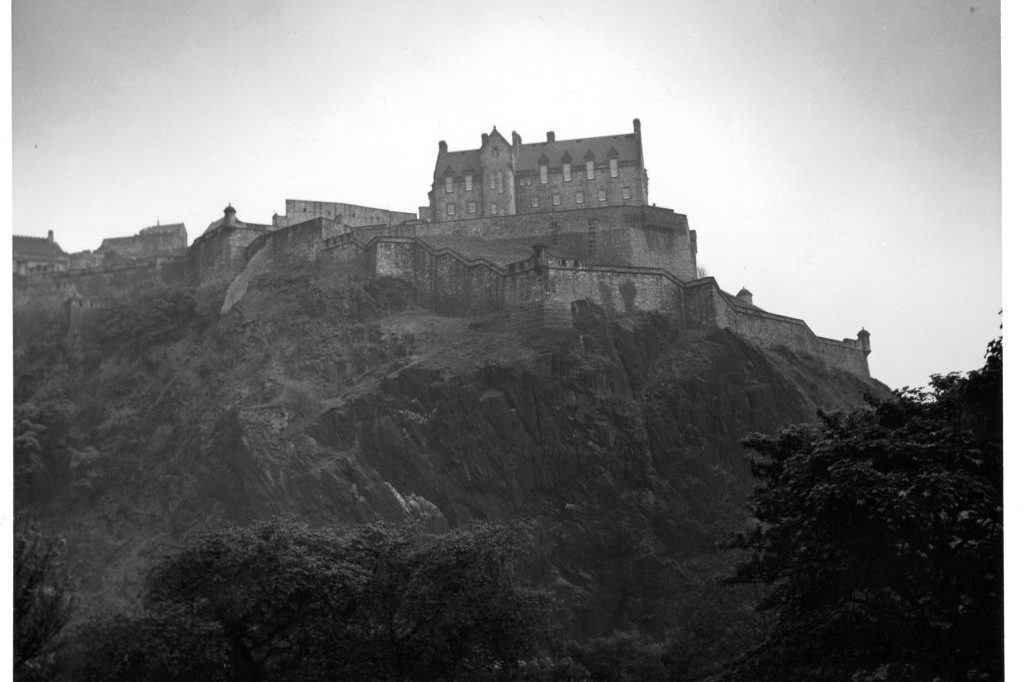

Buffeted by rising sea levels and relentless erosion, Tangier is not so slowly sinking into the shallow waters of the Chesapeake Bay, threatening its ancient community of crab-hunting, God-fearing, Cornish-sounding fishermen with extinction. The Chesapeake, site of the first British settlements in America, has some of the highest relative sea rise on the planet. If Tangier disappears beneath its waves, America will lose a living link to its pre-revolutionary past.

For Ooker though, as for many Tangier residents, man-made climate change is little more than a mythical scare story. “The climate’s changing, I just don’t think man’s the cause of it,” Ooker told me when we met on Tangier last year.“Man ain’t going to control the climate, I think he’s giving himself too much credit if thinks he can do that.”

The sixty-three-year-old crabber shot to fame in 2017 when he debated Al Gore on CNN, questioning the former vice president and environmental guru about whether climate change is truly manmade. Ooker’s determined performance that day earned him a congratulatory phone call from President Trump and a slew of media attention. Trump flags still fly across the island. “The sea level is the same as it was when I was small,” said Ooker. “The real danger to us comes from erosion.”

For Tangier and its way of life to be submerged by the cold Atlantic would be an appalling loss. Despite Tangier being just eighty-five miles from Washington, DC, visiting the island, which is served by ferries from Onancock, Virginia, and Crisfield, Maryland, feels like stepping out of time and space. The Virginia island was first settled permanently in 1686, it is thought, by John Crockett and his sons, who are believed to have hailed from the West Country of England, bequeathing Tangier’s residents a sharp Cornish lilt. Life there is so remote and insular that the accent survives today, blending with local American into a folksy mid-Atlantic twang. (Several residents I spoke to expressed their love of the BBC show Poldark, set in eighteenth-century Cornwall, and said they found the accents pleasingly familiar.)

Theirs is a life of faith and community amid the elements. Tangier’s residents live among their ancestors, whose graves are dotted across the island in tiny cemeteries. The same last names appear again and again: Pruitt, Eskridge, Crockett. Yet today even the hardiest of locals are beginning to wonder if their home can survive. Many have noticed water rising up through their gardens. On some days even the tap water has a salty tang.

“The island is dissolving, it’s turning into soup,” says Earl Swift, author of Chesapeake Requiem, a much-loved book about Tangier. He gives Tangier another two decades at most: “It’s a slow-motion natural disaster that’s really not even that slow anymore. Tangier is not long for the world.” (Readers of an earlier local bible, James A. Michener’s Chesapeake, will recall a similar fate befalls the fictional Devon Island.)

Along with heavy coastal erosion and climate change, strict government rules restricting fishing activity and the temptations of life away from the island’s fierce Christianity are also corroding the Tangier settlement. Residents estimate the population — now in the region of 400 — has almost halved in the past two decades, as young people seek opportunity and employment on the mainland.

To many ears, Ooker’s arguments on climate change may appear irrational and foolhardy. But they also speak to just how unyielding and hardened the Tangier residents have become after centuries of survival out on the harsh bay. “Winter out here, it’s like being an Eskimo, you grew up in it so you know how to survive,” says Inez Pruitt, fifty-nine, the island’s nurse practitioner. (A “copter doctor” visits every two weeks by air.)

Like many on Tangier, Pruitt is terrified of the effects of erosion and believes that unless powerful defenses are built to protect the island’s western flank, four centuries of settlement could come to a calamitous end with one violent hurricane. “If they don’t extend the seawall, Tangier is going to die,” she says. “There’s always going to be changes in climate, ever since Earth has been here. If you want to keep it, you gotta surround it.”

For now, at least, on Tangier the old Chesapeake way of life — which the historian David Hackett Fischer describes as one of British America’s four original “hearth cultures” — survives just about intact. Crab shanties, where the watermen store their boats and equipment, are dotted out in the harbor, passed down from father to son. Already beneath the waves on the island’s southern shore is Fort Albion, built as a base by the British during the War of 1812.

Tangier is also the closest thing you’ll find to an American theocracy outside of Utah: some locals take the scriptures so literally that they won’t cook or use scissors on a Sunday. The island is “dry” and doesn’t sell booze. They’ve also outlawed the lottery on moral grounds, and there is no policeman on the island, because there is so little crime.

One hope for Tangier is tourism. Along with its idiosyncratic culture, Tangier specializes in old Eastern Shore traditions: fresh crabs and oysters, of course; duck hunting; sailing and kayaking, too. It has long golden beaches and bird-filled marshlands, almost giving it the feel of a desert island, despite its proximity to the heart of American power.

Someone who isn’t giving up on Tangier is Rob Baechtel. After a cancer diagnosis gave him just a few months to live, Baechtel decamped to Tangier with his wife Barb, following a long career as a cop on some of DC’s toughest streets. He beat cancer; now he’s determined to help Tangier stave off its own doom. “I’m sixty, so I’ve got maybe ten years left in this,” he told me while mending a footbridge. “I don’t want this island to die.”

The craggy old ex-cop is now the owner of the Brigadune guest house, a bed and breakfast. It’s been his salvation. “I want to be buried here on this island,” he said. “You can chuck me out into the bay if you need to. Just leave me here.”

Like Ooker and Pruitt, Baechtel believes a seawall could be a silver bullet. “Storms are the elephant in the room,” he said. “Without a proper seawall, a category-four storm coming up the bay could completely take us out. So you’re living on the edge.”

What Tangier desperately needs is investment in infrastructure, which is tough to justify until its future is secured. There are some positive indications though.While I was on the island, a group of workmen arrived to install broadband internet. “People have to believe in the future to invest,” said Baechtel. “The Army Corps of Engineers could protect this island with $30 million, it just requires the political will.”

There’s even a plan afoot to introduce a tiki bar on the island, so that Chesapeake sailors can stop by to listen to soft rock and sip piña coladas while watching the bay’s famous pink and amber sunsets. But tradition could be a sticking point. “A tiki bar won’t happen,” insists Pruitt. “Too many of the older church people aren’t going to like it.”

Will the wall arrive in time? With Trump in the White House, this timeworn community had high hopes of political salvation. But with the Democrats in charge up the bay, expectations have dimmed.

“I don’t like what’s going on in Washington, DC, at the moment,” said Ooker, as he ushered me on to one of the tiny motorboats that ferries Tangier’s residents to and from the mainland daily.

Ultimately though, the mayor’s not too worried. Because if worst comes to worst, Ooker will trust to the whims of a higher authority, as Tangier always has. “We’ve got our own place out here,” he said. “If things get too bad, we’ll just secede from the union and go our own way.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.