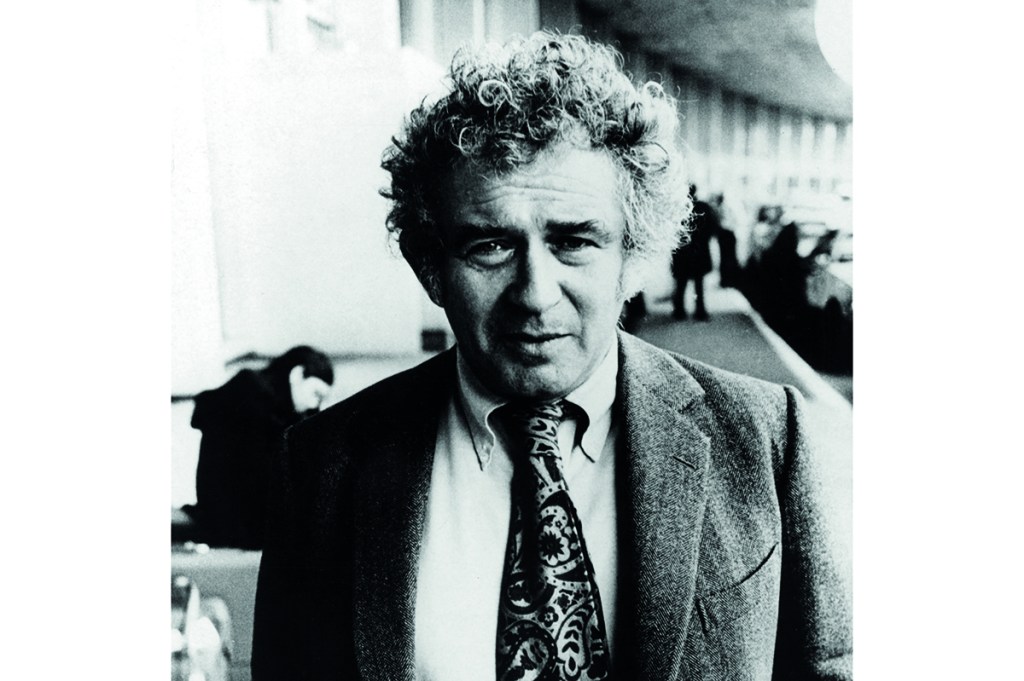

Norman Mailer was born on January 31, 1923, and with the passage of his hundredth birthday there has been a major revival of interest among those who can still read. Norman died in 2007, aged eighty-four, and his first-born son Michael, a talented film director who has since become my closest friend, came over to my house in a slightly shocked state. I was his father’s friend and admirer, so we sat down and drank the day and night away.

A review of the most recent Mailer biography — a hatchet job by a Brit, Richard Bradford — states that Norman could not walk his dog without getting into a fight. Funny what people not in the know will say or write. I was close to Norman for thirty-odd years and never once saw him start something or do anything aggressive. Having said that, he never let anyone step on his toes, a quality I admired. Let’s put it this way: Norman did not put his trust in princes, but in himself, like Papa Hemingway before him.

I remember discussing two of his contemporaries, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, in a round-table format at Elaine’s, the late-night bistro frequented by celebrities and writers and run like a reform school by the formidable Elaine Kaufman. The greatest Greek writer since Homer observed that Mailer, though also of the Jewish faith, doesn’t write from a Jewish-American perspective, unlike Bellow and Roth.

The negative portrait by this Bradford bore is water off the proverbial duck’s back for us Mailer-Hemingway fans. Both Norman and Papa had experienced combat, something I very much doubt any of their critics ever did, and experiencing combat is akin to losing one’s virginity to a real goer. It marks you and stays with you. After combat, a fistfight is like a pillow fight, nothing to write home or brag about. Norman’s description of the carnage inflicted on the human body and mind in The Naked and the Dead illustrated brilliantly the physical and emotional suffering of soldiers. No one did it as well. Mailer never showed triumphalism at American victories over the Japanese because he had seen the price paid by both sides firsthand. And he never liked or trusted officers, like most true grunts. He expressed his contempt for authority time and again.

That’s where he and Papa may have differed. The latter got closer to officers, Colonel Buck Lanham being a good friend and model for one of his major characters. There are no heroes in Mailer war stories, and the powerful are shown as contemptible. His descriptive passages differ from his hero Papa’s. The latter’s prose is spare, lyrical and poetic: In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plains in the mountains. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees.

That’s Papa’s opening to A Farewell to Arms. By contrast, here’s Norman in The Naked and the Dead: “Their legs had lost almost all puissance; for minutes they would stand virtually in place, unable to co-ordinate their thighs and feet to move forward…” Papa is romantic and descriptive about the horror of war, Norman a realist.

I often wonder what Papa and Norman would have written about the debasement of our society nowadays, the something-for-nothing celebrities — hustlers like the Kardashians and their ilk. Both writers dealt with the brutality of life. In fact, it was always present in their writing: bullfighting and big-game hunting for Papa, boxing and skiing for Norman. And both were ready to use their fists, as good men should be — or used to be in the good old days. Hemingway achieved effects of the utmost subtlety with his short declarative sentences, so much so that Ford Madox Ford found the perfect simile: “Hemingway’s words strike you, each one, as if they were pebbles fetched fresh from a brook.”

Both writers reveled in dissipation, gallantry and heartbreak — Mailer has his hero Rojack in An American Dream kill his wife and then bugger the maid — as well as nonchalant banter. Mailer was sweet to people he liked, and was generous with praise. Papa I never met, alas, but he was known to turn on friends when drunk. So what? No one’s perfect. When I asked Norman to teach me to headbutt, he was as gentle as my old German nanny. He boxed every Sunday morning with José Torres, light heavyweight champion of the world, and his son Michael. The latter could easily take him but never showed the old boy up. As Papa would have said, “That’s the way of men.” There was a lot of bombast in both men, as well there should have been, and I would have loved to see either of them respond to questions about gender dysphoria or involuntary celibacy. Where are you now that we need you, Papa and Norman? Although Jewish, Mailer would not set foot in Israel as long as thousands of Palestinians lingered in horrible refugee camps. He once came to my New Year’s party in New York, and a very pretty Israeli girlfriend of my wife’s asked him why he never visited: “Because they don’t all look like you, sweetheart,” answered the tough guy. End of story.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.