When I say “Scottish salmon” what do you see? I bet it’s a muscular twenty-pounder flashing up a river, or a silver grilse leaping out of the water for the sheer joy of it. I bet it’s not a flabby beast, covered in sea lice, possibly half-choked by micro-jellyfish in its gills, living in waters so polluted that the seabed beneath, contaminated by salmon poo, is lifeless.

Fish kept in cages in comparatively calm loch waters do not get the exercise they need to firm up their flesh. They look good on the outside, pink and pretty, but their raw flesh is so soft you can spread it like butter. Fish kept in open sea cages and swimming against rough seas will have firmer flesh, but these farms are perhaps worse: when seals or storms tear open the cages, thousands of salmon escape. And they threaten the wild salmon, by spreading disease or interbreeding in the rivers.

Should you eat wild salmon? Well, you are unlikely to find one, or to be able to afford it if you could. Fishing restrictions and low stocks make them almost unobtainable. If you should be lucky enough to catch a fish in Scotland, you have to put it back.

Salmon farming is the answer. Obviously standards vary, but almost all farms are hugely successful. A packet of salmon fillets currently costs less than a cappuccino.

Forty percent of Scotland’s food exports are farmed salmon. It is Britain’s most valuable food export. It’s also healthy, easily digestible, low in saturated fats, high in omega-3 and takes minimal energy to cook.

Indeed salmon farming is so profitable it can bear wastage that no other form of farming could: one farm lost 50 percent of its stock to disease, sea-lice infestation or suffocation by jellyfish blooms (all a result of overcrowding).

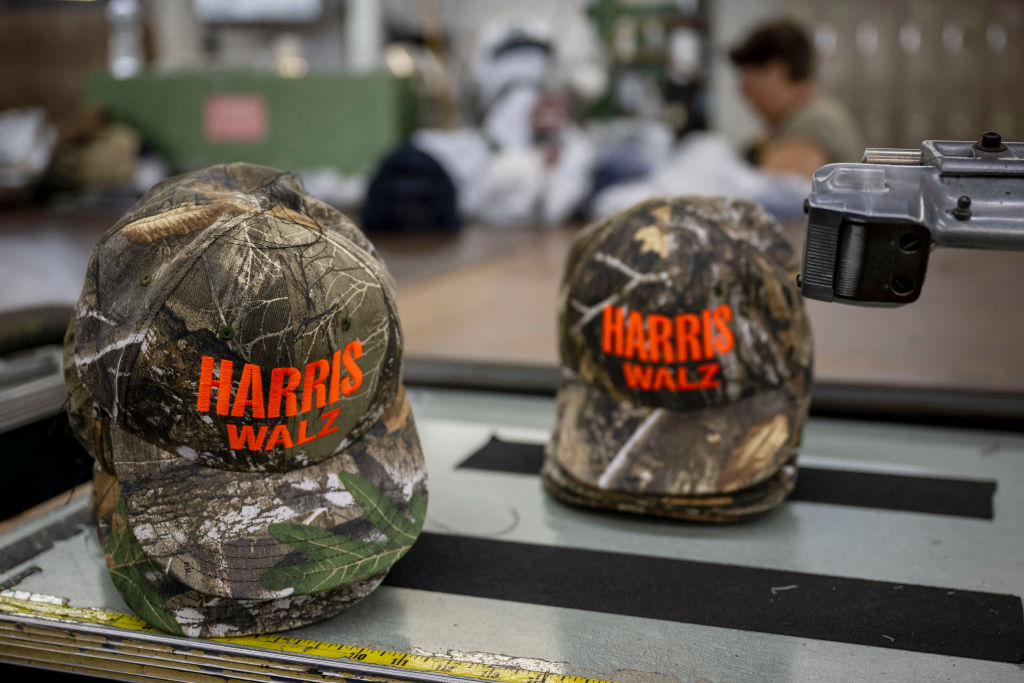

There is a growing movement among restaurants to ditch farmed salmon on grounds of cruelty, damage to the environment and excessive use of chemicals, but I don’t think this will work. The public loves salmon, and will no more stop eating it than they will stop eating chicken because the broilers are raised in poor conditions.

The good news is there is an answer. In Iceland salmon are being farmed on land, without hormones, without antibiotics, without pesticides and with no sea lice or pollution. Silverscale fish are housed in tanks near the shore and seawater filters through volcanic rock aquifers under the farm from where it is pumped into the fish tanks. It flows in and out of the tanks, constantly filtered as it does so. It remains crystal clear, and the sewage is turned into fertilizer for a tree-planting scheme. Sea lice and micro-jellyfish can’t get into the tanks. Hot springs provide all the farm’s energy and warms the water to the ideal salmon requirement of 48°F.

Apologies for sounding like an advertisement for Silverscale but the farm is truly a great example of how fish should be sustainably reared from eggs to kilo-weight fish. The only non-perfect bit of the cycle, not yet solved, is that the fish food contains some wild fish which could otherwise be eaten by humans. But they are working on finding alternative sources of protein. So I’m a paid-up fan.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply