South of France

‘Yes, I will have a coffee,’ said the van driver. He’d driven down to the south of France from Devon. I motioned him to take a pew at the kitchen table and asked him about himself.

Ron was ex-army. Aged 17, he was faced with a stark choice: the building site or the army. Because he’d seen his builder father working in a trench all day with water up to his waist, he chose the army. He joined the Royal Engineers and trained as a driver. In the early 1970s he drove two SAS men around Belfast in an unmarked sedan. That was the job. All day every day. Everywhere Gerry Adams went Ron followed him. Gerry Adams knew he had a tail and would give a friendly or an unfriendly wave, depending on how he was feeling. Yes, Ron enjoyed the army. He even enjoyed his Northern Ireland tours at the height of the Troubles. Loved it, really. Owed it everything.

Back then he had a 50-inch chest and a 28-inch waist. As I could see, now it was the other way around. The legs were still good, though, I observed. Ron’s shorts revealed a pair of the biggest, most convex calves I’d seen for a while. His shaved head glistened with perspiration even while seated in repose and drinking coffee. Occasionally he’d mop it with a handkerchief. The rare smile was oddly coy and comical because his false teeth were too small for his face. His bare arms looked like pages of a calligraphy tutorial book. I liked him. He had that ‘other ranks’ British Army personality that I’d noticed before in others, founded on a degree of acceptance, humility and good humor more normally associated with practicing Buddhists. ‘Situation dangerous,’ one might hear them say —the old army joke—‘but not serious.’

His journey down had been complicated by an unexpected reduction in the frequency of Eurotunnel service to one train an hour, causing a four-hour delay before boarding. This was disquieting news. If the planes stopped flying altogether, I’d been telling myself, there was always the tunnel as an escape route back to old England. If there were no planes or tunnel, I’d be stuck here. ‘Bloody Covid,’ I said. Ron agreed that it was indeed rather trying.

Has anyone he knows had COVID, I wondered? Why, he’d had it himself back in January, he said. He’d caught it in Italy, delivering golf clubs. Of course back then few people knew anything about it and there were no tests or anything. But looking back, it was definitely COVID. He suddenly felt so weak after delivering the golf clubs, he said, mopping his head with his handkerchief, he thought he was going to die. He lay down in his cheap hotel room and the next thing he knew it was morning and he’d been asleep for 10 hours. How he drove home again he’ll never know. When he got back to Devon he went straight to bed and didn’t get up for a week.

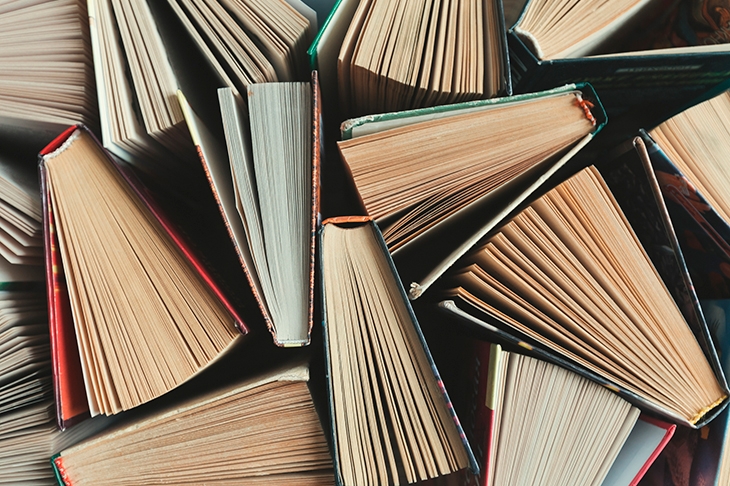

We drained our coffees and walked down the path to unload the Mercedes Sprinter. He’d driven down with a metric ton of my books, his legal upper limit for freight. For this he charged £1,500 (about $2,000) — roughly 50p (or 63c) per book. Ron swung back the rear doors revealing 60 boxes weighing about 45lbs each, packed in a tearing hurry by me last January. They took up surprisingly little space in the cavernous bay. ‘Right then,’ said Ron, spitting on his hands.

Our house has no road access. Each box would have to be lugged up the steep footpath by hand. One box of books carried from the road up to the house would have tested the endurance of any reasonably fit individual. But in half an hour it would be dark. Heavy rain was forecast within two hours. Plan B, then.

At the bottom of the path is a holiday home, now empty. I laid a tarpaulin on the tiled terrace. We’ll stack the boxes on the tarp, I said. Then I’ll cover them and carry them up the cliff at my leisure — if that’s the right expression — the next day and probably the day after that. Ron was visibly relieved to hear it.

We began pulling the boxes off. There was a time when I couldn’t afford to buy books. For the first half of my life I owned half a shelf. Library closures, the advent of charity shops and the internet have made old books accessible and ridiculously affordable. My half shelf had expanded to this maximum van load: each book familiar and cherished; few completely unread. As he lifted the last box and staggered with it to the open door, Ron’s pate was running with sweat.

‘Ever thought of getting a Kindle?’ he said.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2020 US edition.